MEDIA INTEGRATES THEORY AND PRACTICE

Adrian Miles proposed ‘What is the difference between thinking about what things are?’ Like a dog, a bat and snake are things but do they think? Well, they do but humans are set apart because we tell stories.

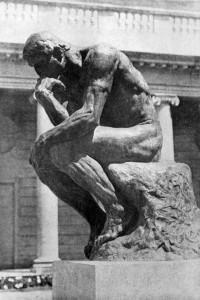

As Descarte said, ‘I think, therefore I am.’

Our job, argues Miles, is to narrate the world, to give it meaning, or put it another way, to document ontography, that is, to be concerned with the relationship between the environment and organic beings.

He posed this line of enquiry:

- What do we know?

- What we don’t we know?

- Of what we don’t know what do we need to find out that matters

- How will we find this?

This does read a bit like a snake eating its own tail and it would be interesting how he would apply this. It was like a friend of mine saying to his girlfriend in a bid to get closer to her, ‘Tell me something about me that I don’t know.’ They broke up.

Miles went on to say that ideas arrive yet he has no idea from where. ‘Ideas are things. There’s High Art and Low Art but when thinking is translated into action it becomes a ‘thing’.

This reminded me of the shows that I’ve put on like, ‘The Portrait of John Howard’. It was a reverse storytelling of the Dorian Gray version where the portrait got better looking and John Howard became more evil and disfigured. I have no idea where that idea came from or why that happened. Yet, I took this idea and formed it into a thing.

Mile raised a provocative thought that the media industry needs ‘in betweeners’. In other words, people who are able to function in a variety of roles or as he coined them, pejoratively, as ‘bottom feeders’. He explained that technology has changed so much that anyone can be an editor, cameramen. You need to specialise.

I don’t necessary agree with Miles on this point. Like any tool, it’s how well you use it. A good cameraman is a good cameraman and excellent editor is an excellent editor. But I will anchor the idea of uniqueness (I don’t, anyway, intend to be an editor rather a writer).

STORY

Lecturer, Liam Ward looked at narrative and non-narrative stories. ‘It’s the kernels that makes story important.’ So with that in mind he provided a set of ‘kernels’, cards in fact and told to make a sequence.

These were the questions in regards to our story.

What are the difference between the three sequences? What qualities, as a narrative, do they have? What sorts of content or fragments/sentences/paragraphs seem to work best as ‘movable’ parts? Why? What characteristics do these parts tend to have?

Then we were told to re-order and reduce the information on the cards. So it looked like this:

1st Sequence

- She woke up far to early

- She ate free food

- She spoke at parliament

- She went to media 1 lecture

- She went to bed and work up in a spaceship.

2nd Sequence

- She work up far to early

- She ate free food

- Turning point card – ‘She lost her voice’

- She spoke at parliament

- She went to bed and work up in a spaceship.

3rd Sequence

- She ate free food

- Turning point card – ‘She lost her voice’

- She spoke at parliament

- She went to bed and work up in a spaceship.

- Accidentally walked into a media conference

This was challenging but its easy to see how you can totally change the outcome of the story just by moving the sequence around.

WHAT IS EDITING?

Editing, Ward instructed, is deliberately smashing things, filling gaps with meaning. A classic example of this is Stanley Kubricks, 2001: A Space Odyssey where the dawn of man throws a bone to the sky it fades to that of a satelite, thus condensing the evolution of humankind in a moment. This, Ward says, is the power of editing, taking us on a journey by showing us two images vastly separated by time leaving our brains to fill in the rest with meaning i.e. story.

Another good example is the 1920s film is the Kuleshov Effect. An actor looks to camera then follows a girl in a coffin. Ah, he must be grieving. But then, back to his face, same expression and it changes to soup. Now, is he hungry. So what happens here is that there is meaning here is meaning outside the shot, before and after.

Thus, we project a meaning for ourselves. This is something I will consider when I attempt the second project.

Furthermore, Ward went on to explain that things only have meaning because we give it to them. Take the Game of Thrones Chair. If it wasn’t for the TV series (ie. given meaning) it would be…well, the most uncomfortable chair in the world! Instead, it is a symbol of power and authority.

Furthermore, its also how often something is broken up can be culturally specific. For example, European films tend to have less edited frames than do American films, and less is explained in them, allowing the viewer to assemble their own story.

REFLECTIVE PORTFOLIO WRITE UP TIME

What stand out for me is:

- the idea that story is dead. That we are the only species that tell stories (well, apart from Klingons).

- images are connected depending on cultural relevance otherwise they’re just an ’empty’ image.

- Space between images – the large the more artistic they can seem eg. Hollywood explains much more. Art films less.

- Lastly, here’s a link which reminded of what Miles was saying about being not being a ‘bottom feeder’ (or inbetweener) in the contracted skills on Blade Runner http://io9.com/142-behind-the-scenes-photos-reveal-blade-runners-minia-1691950942