Tagged: reading

Picked up the wrong book

I just found this article from The New Yorker about comprehension with online reading and training to read deeply on the internet. An interesting market: digital apps to train students in the tools of deep reading.

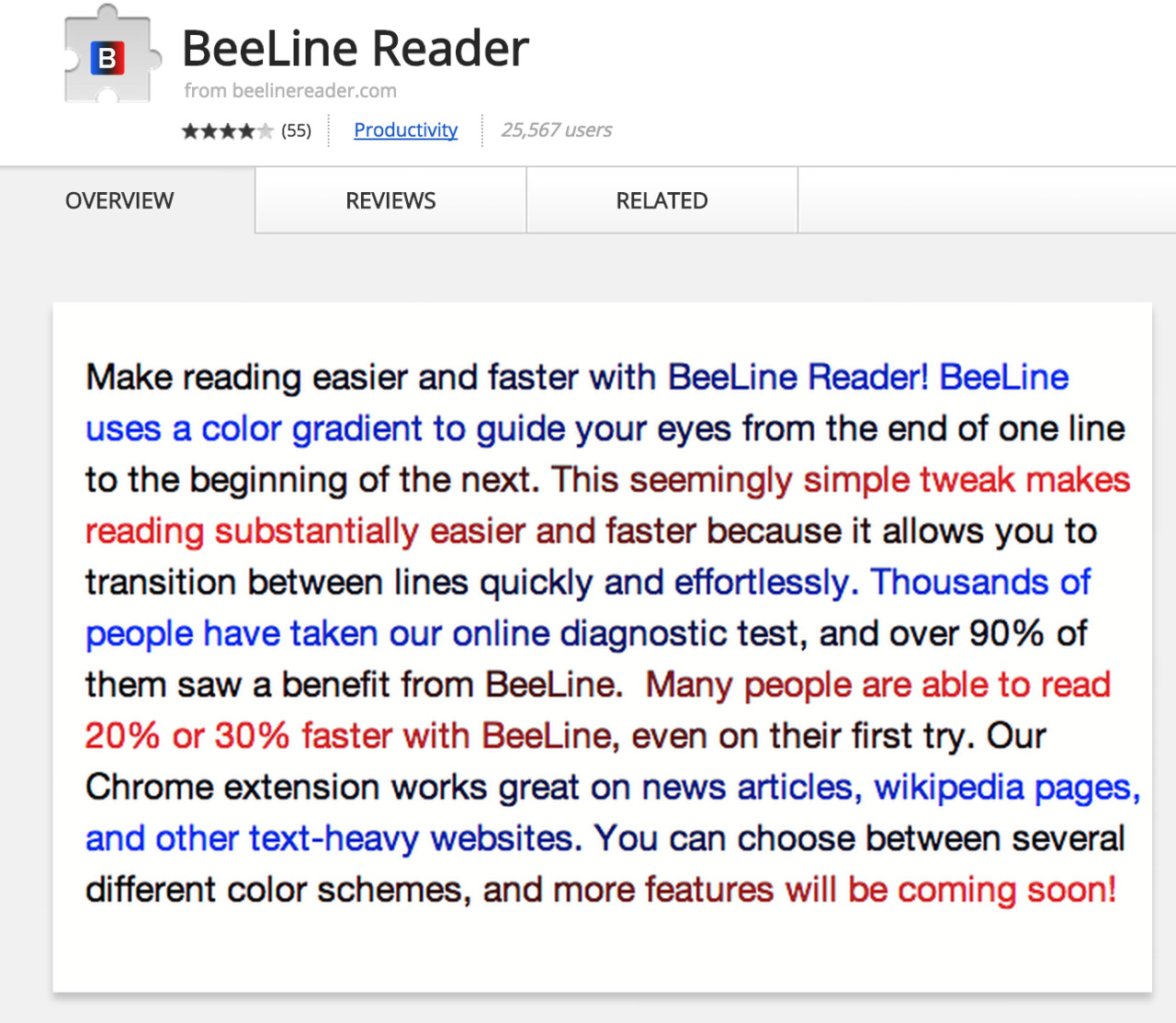

We read more quickly when lines are longer, but only to a point. When lines are too long, it becomes taxing to move your eyes from the end of one to the start of the next. We read more efficiently when text is arranged in a single column rather than multiple columns or sections. The font, color, and size of text can all act in tandem to make our reading experience easier or more difficult. And while these variables surely exist on paper just as they do on-screen, the range of formats and layouts online is far greater than it is in print. Online, you can find yourself transitioning to entirely new layouts from moment to moment, and, each time you do so, your eyes and your reading approach need to adjust. Each adjustment, in turn, takes mental and physical energy.

—

Julie Coiro, who studies digital reading comprehension in elementary- and middle-school students at the University of Rhode Island, has found that good reading in print doesn’t necessarily translate to good reading on-screen. The students do not only differ in their abilities and preferences; they also need different sorts of training to excel at each medium. The online world, she argues, may require students to exercise much greater self-control than a physical book. “In reading on paper, you may have to monitor yourself once, to actually pick up the book,” she says. “On the Internet, that monitoring and self-regulation cycle happens again and again. And if you’re the kind of person who’s naturally good at self-monitoring, you don’t have a problem. But if you’re a reader who hasn’t been trained to pay attention, each time you click a link, you’re constructing your own text. And when you’re asked comprehension questions, it’s like you picked up the wrong book.”

Ryan + Bogost

Ryan’s reading regarded the semantics of a narrative, with the suggested definition: “story is an event or sequence of events (the action), and narrative discourse is those events as represented.”

The following dimensions were also suggested to define what a narrative is:

I like to think about narrative and story because I enjoy reading and writing both fiction and non-fiction, so this reading is interesting to compare these two genres, but I’m unsure of the importance of this reading in regards to what we’ve studied so far in the course. Previously we have discussed in lectures that definitions by definition are inherently wrong and there are always exceptions to the rule, and that we shouldn’t waste time thinking about which box our work fits in to. On the other hand, I have felt strangely liberated by the constraints of the constraint tasks, so perhaps this reading can fit in to the course this way, but I’m still unsure. Ryan mentions the ‘do-it-yourself’ toolkit for definitions based on her eight conditions, so maybe we are able to satisfy ourselves with only a couple of these factors and ultimately define things individually.

Bogost’s reading about lists and literature made me ask myself if our sketch tasks are the film equivalent of a written list. For example, here is a ten second clip of things that define me: guitar, laptop, a candle, etc. It’s quite reminiscent of Barthes’ list of likes and dislikes mentioned in the article.

Books belong to their readers

Chantelle‘s entry this week about books that change each time you read them excites me almost as much as I think they excite her, and it reminded me of something I read once that asked a question along the lines of: what if when we read we are reading what we want to read, or in a sense what our imagination makes up as we go along, ie that we write what we are reading as we read it.

I also think this is the cutest thing I have ever read:

With the aid of technology, we can create millions or trillions or billions (not sure which is bigger) of stories.

While I think the idea of an ever-changing and never-ending book is amazing – I mean we have all mourned that heartbreak of when a really good book ends, right? – I can’t help but think it already exists.

It’s funny, but it seems each time I read James Joyce’s “Ulysses”, it’s a different book, begging the question: Has the book changed… or have I?

It’s one of Ted Mosby’s quintessential quotes, and it gives a nice insight into this idea. My life has literally been changed by certain books: they have this power of changing the way you think and subsequently how you go about your life. And I like to believe I grow as a person and a creative as I open my mind up to new ideas. As our experiences grow, our perspectives change, our prejudices are disrupted… these factors all influence who we are, and often re-reading a favourite book after a few years can feel like reading an entirely different book all together. Has the book changed, or have I? I know that I’ve changed, but I don’t see why these concepts are mutually exclusive. Books belong to their readers; we impart our own meaning; we construct our own knowledge from the information presented to us.