Chantelle‘s entry this week about books that change each time you read them excites me almost as much as I think they excite her, and it reminded me of something I read once that asked a question along the lines of: what if when we read we are reading what we want to read, or in a sense what our imagination makes up as we go along, ie that we write what we are reading as we read it.

I also think this is the cutest thing I have ever read:

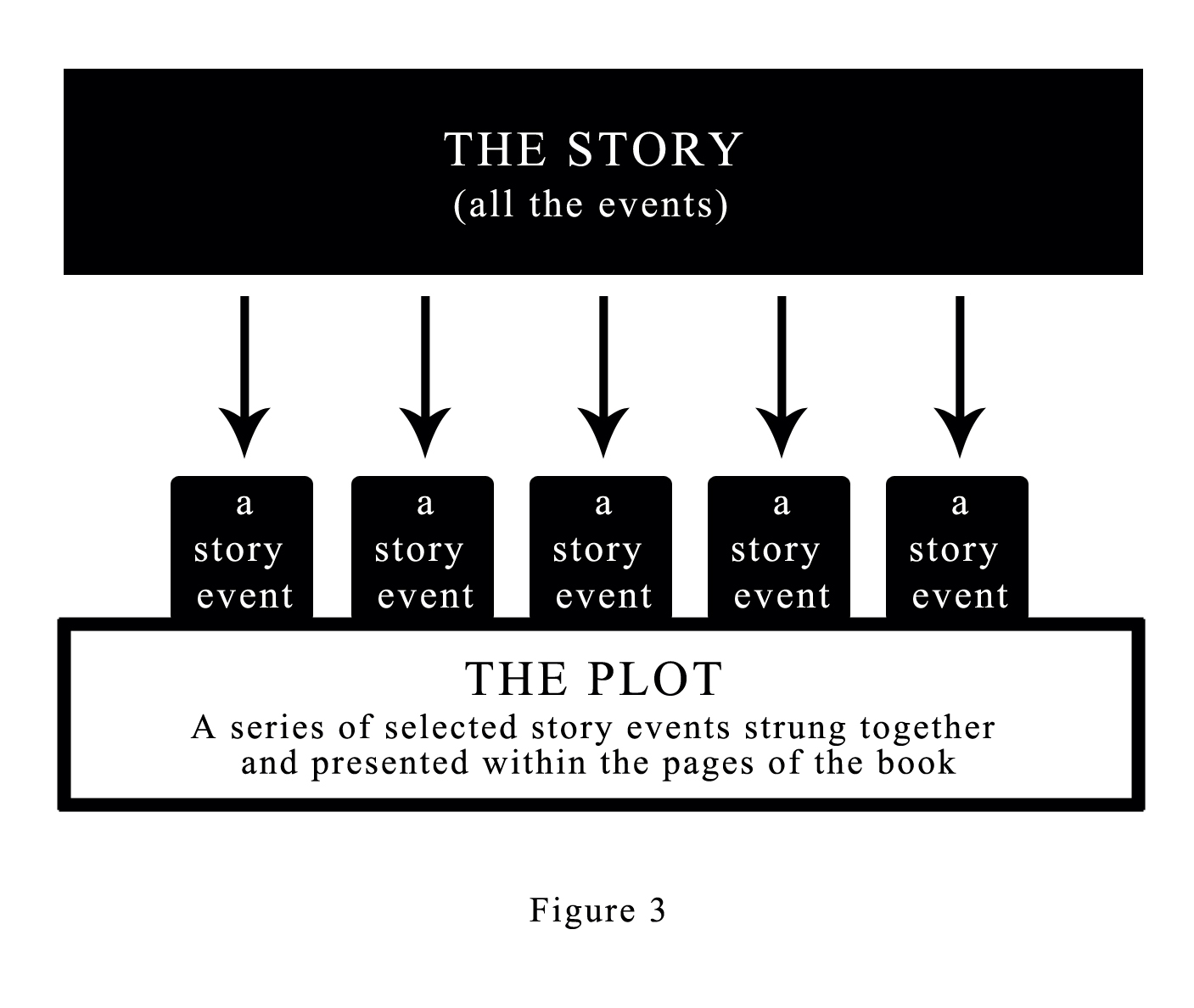

With the aid of technology, we can create millions or trillions or billions (not sure which is bigger) of stories.

While I think the idea of an ever-changing and never-ending book is amazing – I mean we have all mourned that heartbreak of when a really good book ends, right? – I can’t help but think it already exists.

It’s funny, but it seems each time I read James Joyce’s “Ulysses”, it’s a different book, begging the question: Has the book changed… or have I?

It’s one of Ted Mosby’s quintessential quotes, and it gives a nice insight into this idea. My life has literally been changed by certain books: they have this power of changing the way you think and subsequently how you go about your life. And I like to believe I grow as a person and a creative as I open my mind up to new ideas. As our experiences grow, our perspectives change, our prejudices are disrupted… these factors all influence who we are, and often re-reading a favourite book after a few years can feel like reading an entirely different book all together. Has the book changed, or have I? I know that I’ve changed, but I don’t see why these concepts are mutually exclusive. Books belong to their readers; we impart our own meaning; we construct our own knowledge from the information presented to us.