Week #6??? I did what I thought I couldn’t and took a little off week.

45 Years (2016) dir. Andrew Haigh

11/04/16

A sensual piece from Haigh, almost acting as a companion piece to Michael Haneke’s Amour (2013), but with tragedy in truth as opposed to loss. Not too much to say about this as I was deathly tired when I saw it, and walked 20 minutes back home only to realise that I’d left my wallet in the cinema. A lady behind me bawled her eyes out. Big ups for the ending, and Haigh’s effortless and restrained direction. ★★★½

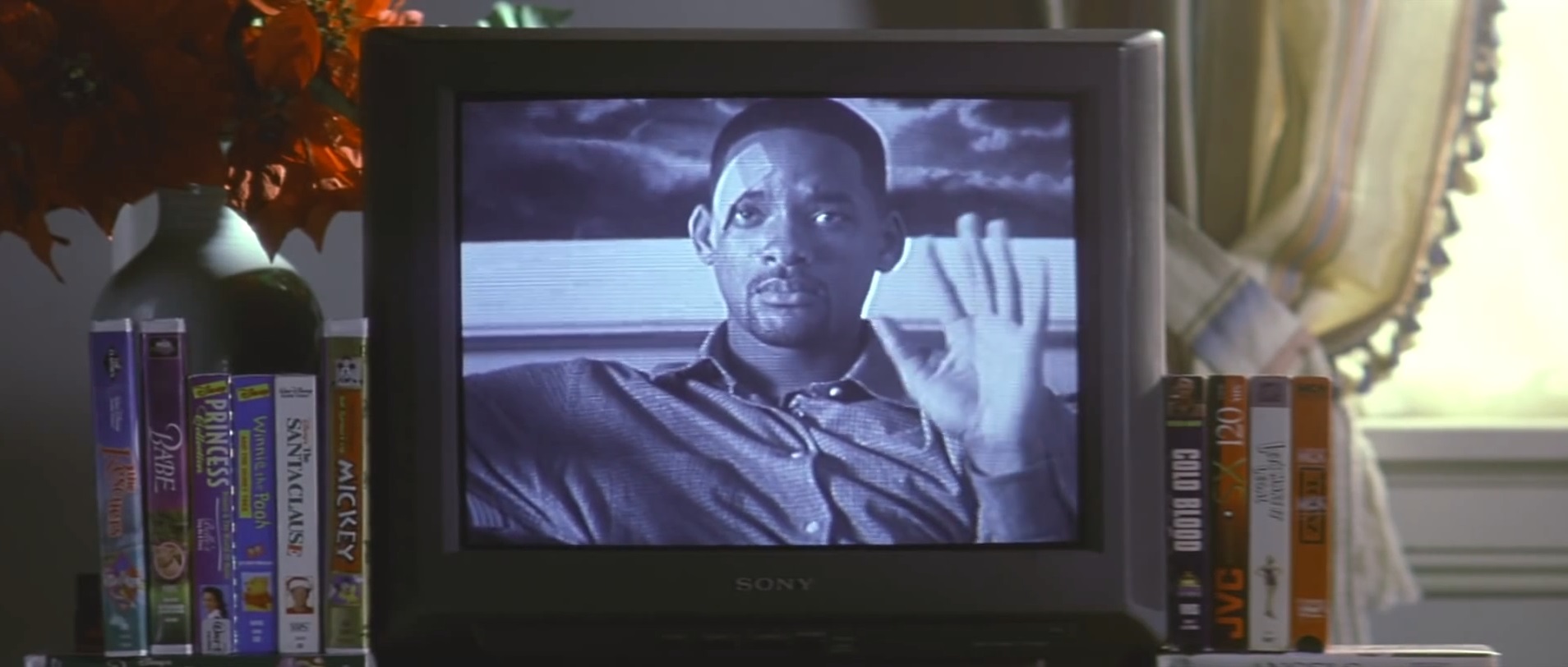

Enemy of the State (1998) dir. Tony Scott

12/04/16

Ah, vulgar auteurs, how I love you–some of the most interesting and visually creative directors working today (I’m looking at you, Michael Mann) fall under this umbrella, and Scott is as much of an auteur as the rest. Longing the day when I can marathon his catalogue.

Written for Letterboxd:

Humanity captured as fluctuating waveforms, blips on a radar, man’s physical existence bound spatially by invisible frequencies (the The Conversation homage) where the truth is perceptible only through deep lenses or played back on a tape. Conspiracy trumping conspiracy, where the state of paranoia is stomached because that’s all there is left to bear (“Baby, listen to this fascist gasbag.”). Paranoia as personal assets reimagined as polygons floating in government databases (who knew what Jack Black was capable of). Scott poses strands of the NSA as bumbling goons, hired thugs with their only dialogue colloquial (and always concerning haircuts); people who steal kitchen appliances for the fun of it (“I’ll be back for my blender.”), who hold all the control but know not what to do with it, always caught second place in a perpetually escalating hell-fire of a race (which concludes customarily in an epileptic culmination of blood and gunfire). A sensationalised view of American privacy of government property through and through, though not without Scott’s action film degradation (this is a Jerry Bruckheimer production after all) which keeps activity high but fulfillment low. I still haven’t seen The Conversation, supposedly this film’s Big Brother? ★★★½

McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971) dir. Robert Altman

13/04/16

Altman season has started at the Cinematheque!!! Here, the man (the myth, the legend…) crafts the perfect ‘anti-Western’, a film less concerned with the stand-offs and the high-stake gang tensions than the power of capital and forbidden love. McCabe & Mrs. Miller is a sensory overload; in usual Altman fashion characters speak all the time, all at once, as Leonard Cohen bursts the film into episodes of sorrowful Western ballots and cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond boasts a widescreen Panavision spectacle (best for Westerns). Seen in not so glorious 35mm–never seen a print looks this rough. ★★★★

3 Women (1977) dir. Robert Altman

13/04/16

rewatch

Written for Letterboxd, last August:

A vague, sensually confounding piece, a dream on-screen, a babbling dreamer and a graceful outsider’s formation of an inexplicable relationship. I am deathly in love with Altman’s style in every sense, his inquisitive zooms and ambient conversation, his free-flowing character interactions and longing shots. The recurrence of fantastical, feminine creatures and clear influences from Bergman’s Persona, along with the fact that the film literally is based on Altman’s dream leave something deeper to be found, uncovered and desired.

Written for my blog, now:

I feel like my thoughts on this have stayed in line with my previous evaluation, though I’ll be damned if someone watched this alone at home and found it nearly as hilarious as the people in my cinema did–whether they were laughing at it or with it I don’t know. Likely a punch to the gut to many in the final minutes when, in a dreamy haze of superimpositions and tight strings, the more invisible titular 3rd woman has a miscarriage. The entirely of the concluding ~20 minutes is haunting, goosebump-inducing cinematographic fear. I don’t know if Altman can top Nashville (1975) at this point. ★★★★

I’m ready to get back into the action next week.