edit

verb

- to choose material for and arrange it to form a coherent whole

- to expunge; eliminate

- to prepare by deleting, arranging, and splicing, by synchronizing the sound record with the film, etc.

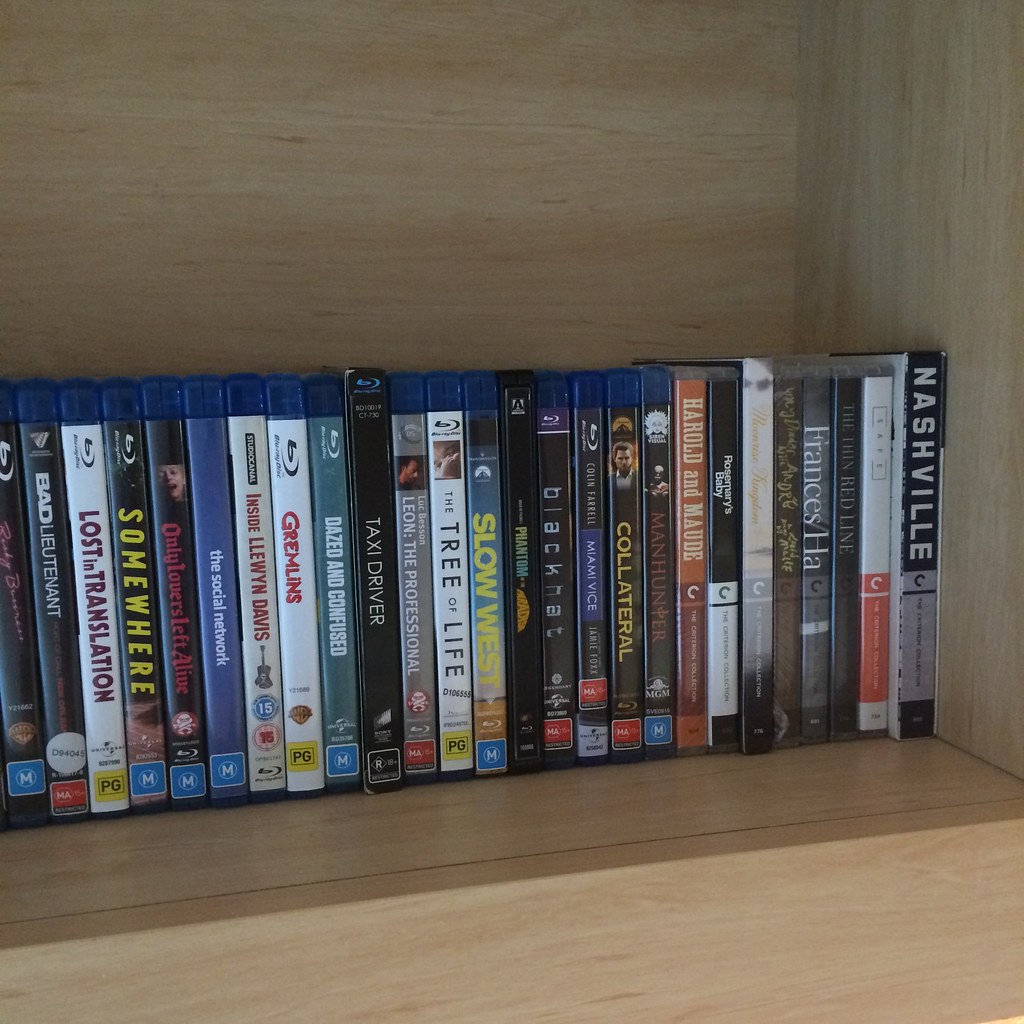

Editing is one of the most underrated techniques in the world. While watching a film most people fail to properly acknowledge the beauty of the edit. If you walked out of the theatre and quizzed your friends on their favourite aspect of the film, how many do you think would pick editing as a highlight? Much of this arises from the fact that the majority films these days are generally edited coherently, ensuring basic temporal and spatial continuity–and it figures, editing is so frequent and camouflaged that it becomes hard to notice it, let alone grade it. Some will say that good editing is editing you don’t notice at all, and other citations range from “Movies become art after editing“, and “The film is made in the editing room“. So in order to fully appreciate the edit it’s necessary to take it back a step (or in this instance step all the way to the opposite end of the spectrum) and look at bad editing: the infamous basketball scene from Catwoman (2004).

It doesn’t help that the scene is deeply cringeworthy at a base level (how you gonna do that in front of those kids, Catwoman?); the sporadic and haphazard editing only makes the scene incomprehensible and, in many ways, unwatchable. What could have been achieved in less than 20 cuts is done in ~130 of the most purposeless and ugly shots of the 21st century. The cuts hold no weight and bear no tension, lifelessin comparison to the masterworks of a Leone or Kurosawa. Catwoman itself was a disaster, so its incoherence can’t be entirely blamed on the editors (Halle Berry later blamed Warner Brothers: “Thank you for putting me in a piece of shit, god-awful movie… It was just what my career needed.“), but when the job is put in the right hands, the results can be electrifying.

As touched on by Jeremy Bowtell in the week #2 lecture, editing is as much about the ‘spaces between‘ as it is about juxtaposition and the combining of parts to create new meaning. Film editor Walter Murch (2005) [whose credits include Apocalypse Now, The Godfather: Part III and Jarhead] argues not only that ‘the cut [should] reflect what the editor believes the audience should be feeling‘ at a certain moment, but should ‘advance the story‘ and ‘occur at a moment that is rhythmically interesting‘. So when these suggestions are applied to a film like Catwoman, where does it rank? If random and volatile zooms and cuts are your thing, then obviously you’re in heaven, but to the average person the frequency and meaninglessness of the editing is jarring. Sometimes it’s beneficial to keep things simple.

A film like La Jetée (1962) relies heavily on editing; its existence is central to its use of, and with these restrictions Marker succeeds in creating something wholly unique and wonderfully spellbinding. An album of b&w photographs, a few simple cuts and a little help from an insightful narrator is all it takes to build a world from the ground up. A scene doesn’t have to be a violent flurry of transitions, like in Catwoman, but more a methodical and structured arrangement of shots, like in the scene below: Sergio Leone’s The Good, The Bad and The Ugly (1966).

Morricone’s scoring here also plays an enormous part in the creation of tension between the three central characters (a touch easier on the ears than Mis-Teeq’s Scandalous) but at its simplest it remains one of the most sweaty-hand producing scenes ever put to screen, achieved in half the amount of shots in Catwoman‘s basketball scene and with a 100% higher success rate. A true emotional high.

Here, less is more, but excess isn’t always detrimental. Take the stairway shootout from Brian De Palma’s The Untouchables (1987) as the perfect example:

Utterly absurd but undeniably engaging; a true nail-biter. De Palma’s trademark slo-mo (and intimate focus on set pieces) elevates a basic gunfight into a gritty, edge-of-your-seat extravaganza complete with high-stakes pram down the stairs action (coincidentally also scored by Morricone). All in all, there is no one perfect way to edit. Much of the style depends on context, genre and overall meaning, the emotions attempting to be conveyed or the tension attempting to be exuded. The beauty of the edit is something to be appreciated, no matter how many times it involves Halle Berry groping a man on the court.