This, is the Creative Commons Niki that I’ve been working on for my final assessment. At the current point in time, I do not know how to upload it to the actual CC Niki on the Networked Media blog, so I’m leaving it here for the time being… Hopefully I can figure it out soon! Also, when you click the link, make sure you download it so that it works properly.

Category Archives: Interesting

The Verbosely Voided Harey Fish

The fish trap exists because of the fish.

Once you’ve got the fish you can forget the trap.

The rabbit snare exists because of the rabbit.

Once you’ve got the rabbit you can forget the snare.

Words exists because of meaning.

Once you’ve got the meaning you can forget the words.

Where can I find a man who has forgotten words?

That’s the man I want to talk to.

– Chuang Tzu

HULLO! (to be read in Hugh Laurie’s voice when he plays Lieutenant George)

It’s been a little while. Which, on one level is a shame, but on another, perhaps reflects something else but my bottomless pit of enthusiasm for university when the end of semester approaches.

Here are a few quotes from my Ethics lecture that I found interesting. They are in relation to Olivero Toscani’s advertising work for Italian clothing brand, United Colours of Benetton.

Controversy arose when Benetton released an advertising campaign that consisted of quite shocking images stamped with the Benetton logo.

McKenzie Wark’s criticism of the campaigns negative reception…

“Of course, Benetton are seeking to gain commercial advantages from the display of these images of war and murder and death. They are no different from a newspaper or the TV news in this respect…In good bourgeois fashion, intellectuals make rules about what is proper cultural behaviour – we can have the spectacle of death in our newspapers and in our art galleries, but not in advertising. Like the man who insists his wife be faithful, but who frequents the bordello twice a week, intellectuals are not terribly consistent when setting moral parameters for the image.”

and Toscani’s personal view on the matter…

“Advertizing is the richest and most powerful form of communication in the world. [Even so] we need to have images that will make people think and discuss. Ad agencies…are far too comfortable. When the client is happy, they stop trying. They don’t want to know what’s going on in the world. They create a false reality and want people to believe in it. We show reality and we’re criticized for it. Our advertising is a Rorschach test of what you bring to the image. You can see a news photo of the fighting in Sarejevo and it’s in context; it conforms to your expectations. Shocking violence in the News is normal. But when you take the same photo out of the News and put a Benetton logo on it, people pause and reflect on their position on the problem. When they can’t come to terms with it, they get mad at us. When journalists focus on strange and serious topics, nobody criticizes them for trying to sell their stories to the media. Yet, when an advertisement touches on a real problem, everyone is immediately up in arms and protests that it’s in bad taste. It seems that an advertisement which misleads the consumer with deception and lies is considered more correct.”

Unlecturing

In response to the unlecture, where Adrian attempted to blow our minds with the notion that the internet was not, in fact, a virtual space, but was actually very physical with very real world consequences.

I think the question was, “What does it matter if there are more mobile phones with internet connections than there are people on the planet? Does the internet actually exist if we aren’t using it?” In essence at least.

Adrian responded by giving examples of all of the reasons that the internet existed in physical space, and how there was a literal, measurable, carbon footprint for every email that we send (and that, it is reasonable to describe spam emails as physical pollution).

(One of the things he failed to mention, in terms of how large Google was as a company – “Google uses more electricity than Melbourne” – was how it is storing some of it’s most recent data farms. They eliminate the problem of real estate costs by floating their servers in the ocean.)

In response to this, I agree, the internet does have a physical presence on the world. However I think the distinction lies in the fact that is is the infrastructure that takes up the physical space, and the internet itself (I suppose this really comes down to a definitional argument; what is the internet?) remains virtual. I cannot touch Facebook any more than I can touch this blog post. I can touch a server, or a screen, but not the literal thing in itself.

Similarly, I cannot access the internet without a computer or a smartphone. The internet can still exist, in terms of the fact that servers, fiber optic cables (oh Tony), data centers, technicians and electricity can exist, but without a medium through which to access it, it doesn’t exist in a practical sense. And if a person is only able to access the internet through one medium at a time, there seems little point in championing the fact that there are more mobile phones than there are people on the planet.

It seems a little like owning more than one pair of the exact same glasses so that you can read different books while wearing them. One pair for fiction, the other for biography. An iPad for social media and a computer for working.

It almost becomes an existential argument, “If a tree falls in a forest…”, and ties quite will into what we were talking about in philosophy and quantum theory, and how perception of a thing alters the physical state of the thing (Schrodinger’s Cat), but that isn’t what I imagine Adrian had considered when he was answering the question.

(Strange how we inevitably alter the context of a thing in order to suit it best to our field of specialty/interest.)

Self Organising Networks?

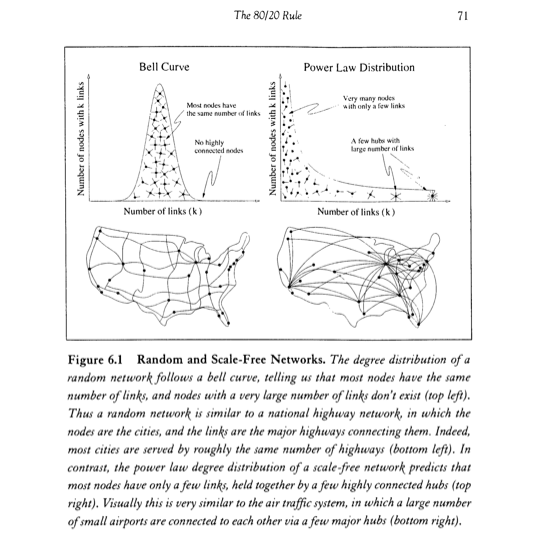

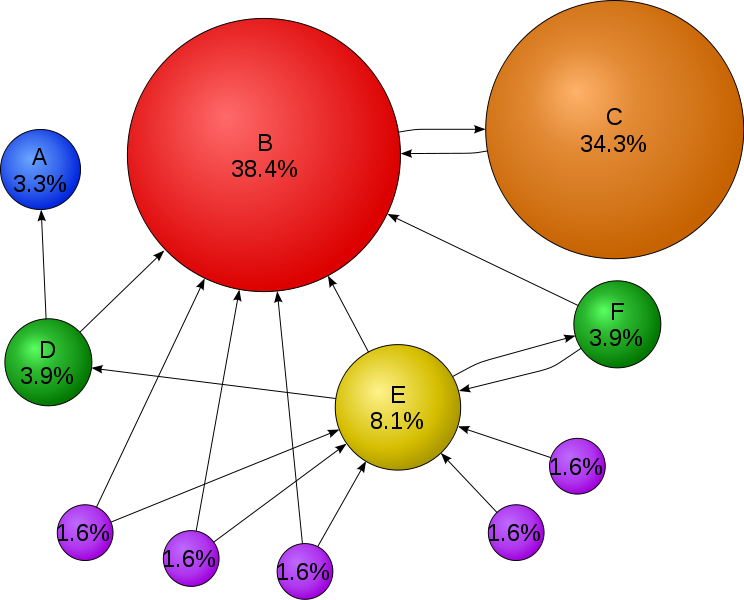

One of the readings for this week, a chapter in a book by, Albert-László Barabasi, called Linked: How Everything Is Connected to Everything Else and What It Means for Business, Science, and Everyday Life, discusses the idea of the 80/20 rule.

It is basically the idea that 20% of things do 80% of the work, leaving the other 80% to do 20% of the work. It is a phenomena seen across the board, from 20% of pea pods producing 80% of the peas, to 20% of people earning 80% of the money, and is to do with what is known as a Power Law.

“Gutside academia Pareto is best known for one of bis empirical observations. An avid gardener, be noticed that 80 percent of bis peas were produced by only 20 percent of the peapods. A careful observer of economic inequalities, be saw that 80 percent of ltaly’s land was owned by only 20 percent of the population. More recently, Pareto’s Law or Principle, known also as tbe 80/20 rule, has been turned into

the Murphy’s Law of management: 80 percent of profits are produced by only 20 percent of tbe employees, 80 percent of customer service problems are created by only 20 percent of consumers, 80 percent of decisions are made during 20 percent of meeting time, and so on. It has morphed into a wide range of other truisms as well: For example, 80 percent of crime is committed by 20 percent of criminals.”

(This is the third time I have tired to upload this post, and the third time it has failed after I have rewritten it from scratch. It’s enough now. Just read the article and think what you want.)

Unlecture Week 7

So, after listening to Adrian talk about the death of context for half an hour, I wasn’t able to restrain myself, and wrote a post about why I disagreed with it. Here is what I wrote.

“My initial reaction was to want to write a post about this immediately, but as the case was, I had a two hour class right after the ‘unlecture’, and was unable to. This might prove to be a good thing, as my possibly emotional, and probably unreasonable reaction has since been tempered and I’ll no longer be shooting from the hip, so to speak, and might be able to argue this point better.

In essence, I disagree on several different levels, with what was discussed by Adrian in the ‘unlecture’ this afternoon. I understand his self admitted (seemingly in a keen way) position as devil’s advocate for these slightly challenging ideas, and for that reason, I assume no personal offence will be taken. I agree with some of your more progressive notions; the death of the book other than that as an object of literary study and the idea that as producers and that we are not being paid for our product but for the experience had by the consumer when using the product. Today’s discussion, however, was different. Not only because it challenged long held preconceptions about the role of an author, but because it seems to approach the argument from a limited point of view.

The main notes that I took, to help me remember exactly what heresy you were promoting, was that it is impossible for the context of a work to survive, and that an author has no control of the interpretation of the work by the audience.

On the second point, to some extent, I agree. An author is not able to control how their work is read. A Muslim will read Dante in a very different way to a Christian. A report on the success of an agricultural technique used on a farm in New Zealand will be read by an Ethiopian in a very different way to a Norwegian. That is the nature of context. Everything is subjective, and there is categorically no possible way to have perfect communication. No matter how you say something, it will be interpreted in different ways by different people. Loaded language used by journalists will mean something different to me, than it might someone who hasn’t studied media. That is the nature of language. It is imperfect. Which leads to it’s own plethora of problems, none of which I have much room to discuss here.

His other proposition, however, that context cannot survive once a work is published, or produced, is what I do have a problem with.

Context, is everything. To suggest that one should take a work as an isolated incident, removed from the author and the time it was published, it ridiculous, plain and simple. How can you possibly remove a work from it’s context. And I don’t mean that as, “How could you possibly, it simply isn’t right (morally) do disregard such a long standing tradition”, but rather, that it is not possible (literally). How can you achieve a higher objective plane where the context of a work no longer affects an interpretation of it?

I remember reading somewhere once, that to read and understand Dante, you have to be a Christian for as long as the reading takes, or at least, words to that effect. To understand the author, you must insert yourself into the context of the author, in order to best understand it. How, otherwise, would you be able to marvel at the Wright brothers achieving flight for the first time, if you refuse to allow yourself into the context that is a flightless 1903. For the whole of my life, flight has been very achievable and is done thousands of times every day across the world. Who cares if the Wright brothers did it 110 years ago? Because of the context. It is in the context of the event that flight had previously not been achieved by humanity, thus making it an enormous step forward for us as a species. It was the context, as was illustrated in an interesting YouTube video about who certain people are successful, that showed they were one of several teams attempting flight at the same time, and were by no means the most financially or materially supported. That similarly increases the significance of the event.

If context cannot survive with a work, why is it that only last semester, while studying Kafka, Linda Daley suggested to us that we read his diaries to better understand his work? And that to read more of his work, including his articles, autobiographical pieces, short stories, and other people’s accounts of him, would also help our understanding of him.”

This was unfinished, but I think the points still stand by themselves. After I wrote that, I had a chat with Eliot about what exactly Adrian might have meant, and he suggested that he might mean it more specifically in the context (HAH!) of hyper-text narratives. And with this, I would agree. That is the function of the hyper-text narrative. To remove the authors context in order to give more agency to the reader.

But still, while a reader might have 30 options as to where the story goes next, those 30 options are still somewhat a reflection of the authors own context. A hyper-text narrative written in 1890 in Texas (supposing there were any hyper-text authors in Texas in 1890) might write about an adventure across the south of the United States, and as the protagonist, you come across a seated black person on a packed bus. Your 30 options might then be variations on how you might remove him from his seat so you are able to sit down. That might be a perfectly justifiable course of action in the context of 1890’s Texas, but in the present context, we might struggle with the ethics of choosing the best way to remove a person from their seat, because they are black, from the 30 options presented to us. The context of the author then affects us today, when we read the work. We are unable to avoid our own context while reading it (as is the nature of context), but similarly, we are unable to avoid the authors context as the choices he gives us within the hyper-text narrative will inevitably be choices that seemed reasonable to him when he wrote the text.

Perhaps, as Eliot suggested, Adrian worded his argument rather too strongly, so as to best carry his point, and for that, I might forgive him. We are all prone to exaggeration on points that we believe passionately about, and as his passion seems to be the forward progression of media and cultural texts generally, it makes sense that he might push his point strongly.

Thoughts on that?

X&Y

When you hear X&Y, it’s not surprising that your thoughts turn instantly to the popular Cold Play song, from the album of the same name released in 2005. After selling 13 million copies, this is understandable.

(After writing the first sentence of this, I thought of dear old Patrick and his long and detailed monologues about various albums and artists. Though as my intention is to neither bore you or ax you to death, I might get to the point.)

Forgetting this, and basing the title purely from a quote from Albert Camus‘ novel, The Stranger, I decided to call a short clip I made last semester X&Y as well. It was for a class called Editing Media Texts.

The task was to generate 2 mins multimedia aiming to serve as a self-portrait to present as our major assessment. There was, however, a catch about this. Firstly, all of the sources material had to be publicly available, meaning we had to get it from either Wikimedia Commons or Archive, so as not to be breaching copyright. Secondly, we also had to meet these criteria:

- No more than 50 words of text.

- Seven still images.

- Two videos.

- Two soundtracks: one ambient/music, the other voice track.

These criteria made the task more interesting, and more difficult at the same time, which in the end, turned out to be positive.

Have a watch of it, and let me know what you think, either here, or on YouTube.

As We May Cite

The Bush article, As We May Think, is referenced in a lot of the other readings for this course.

Is the importance of an article the number of times it is cited by other sources? Google thinks so.

Dying Breath of the Book…?

One of this weeks readings was a section from a book, The End of Books — Or Books Without End?: Reading Interactive Narratives, by Douglas, J. Yellowlees. It was quite long, which was rather taxing, but it did make some interesting points about several issues, including the future of the book in the face of e-readers and new technologies.

One interesting passage argued that even though technology has passed the book by, history suggests to us that this does not necessarily mean the end of the book.

“Even if ou became used to reading in this way, it is hardly likely that digital media like hypertext are going to supersede books, regardless of how much critics like Miller or Birkirts fret over the fate of the book and le mot juste. Radio and cinema went foraging for slightly different niches once television debuted on the scene, and ballooning numbers of video rentals, airings on premium cable and satellite channels, and pay-per-view showings have all helped recoup losses for films that were absolute dogs at the box office – and unexpected boom for Hollywood. It is hard to imagine books becoming the horse of the twenty-first century – a possession that has lost so much of it’s utility that only the well-to-do can afford to have one around.”

The article places the discussion in the context of hypertext, and how these kinds of technologies will affect traditional reading experiences. What, for example, would happen if you were never able to read the same book twice? And that by virtue of your past experience, will read a text one way, as opposed to if you reread it again two weeks later?

This question is much less of a hypothetical example and more of a reality once we admit the possibility of the self being as fluid as a choose-your-own-adventure novel. The question then becomes, if we are now being forced to be aware of this fluidity of our own perception in terms of the different texts we consume through specifically built structures like hypertext, will that affect our conscious reading of traditional paper books?

If we become aware of the fact that we never take the same path through Wikipedia twice, even when searching for the same information, then will that awareness extend to when we are reading a hard cover of Jane Austen? Will we begin to consciously realise that our attitudes to a character we may have hates on our last reading, are perfectly able to change on this reading due to a near infinite number of different variables?

The question was summed rather perfectly by Brian, when he compared the discussion to the quote by the Greek philosopher, Heraclitus, “No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man.”

Late Than Never?

I just read through the article that was set for us to read several weeks ago, As We May Think, by Dr. Vannevar Bush.

I thought the article was quite interesting, especially as it showed what a visionary Bush was, and what he was able to suspect might be possible in the future. Especially his comments on the technology of photography, and about the possibility of, “dry photography”. As he suspected, “often it would be advantageous to be able to snap the camera and look at the picture immediately”. This is digital photography. And we must not forget that he wrote the article in July of 1945, close to 70 years ago.

Another part that I thought was important was his foresight to notice the possibility of information overload, and that the point would arrive where the content being created was greater than that which was possible to consume. He used the example of Mendel, whose discovery of the laws of genetics, which was lost for a generation as it was not read by the few people who could put his thought into practice and make the discovery public. This is now an even greater concern following the advent of the Internet. What if the key to curing the AIDS virus was stored away on a hard drive in a university somewhere, unread and unappreciated. The idea reminds me of this passage from a letter by Antoine de Saint-Exupery, the French author and aviator. (I also find it interesting that Bush published his article only 13 months after the premature death of Saint-Exupery. The fear of too much information was a common worry in those years.)

“I prefer the sale of a hundred copies of a book I don’t have to blush for to the sale of six million copies of a bad book. This is justified egoism, because the hundred copies will carry much greater weight than the six million ever could. The belief in number is one of the fallacies of the age. It is the most select journals that are the most illuminating; the ‘Discourse on Method’, even if it had no more than twenty-five readers in the seventeenth century, would nevertheless have changed the world. ‘Paris-Soir’ with its yearly tons of paper and it’s two million readers has never changed anything.”

Does anything we write have any weight anymore? Is what we are writing pushing the human race forward, or even having any positive or constructive influence on the world around us?

It is also the only ethic that worries me about this subject. The notion of being a content producer. For who is to say that I am only adding to the clutter and chaos of information on the internet by writing here? Does the fact that I can publish my own content mean that I necessarily should? What is really more valuable to be found here than in the angsty ramblings of a 13 year old girl with a Tumblr account? Who am I, really, to say anything?