Are humans in control of our own destiny?

I’m not going to lie; I struggled with yesterday’s lectorial quite a bit. It was on the theme of media materialism, which is to say (I think), it was about media as physical artefacts rather than theoretical concepts. Daniel was our lecturer again and he explained to us concepts such as the ‘anthropocene’, or the age of man on earth, and he discussed a whole range of examples of end-of-the-world scenarios on film. At the end of the lecture, he asked us to blog on one of five prompts, one of them being my choice in the title above, ‘humans are in control of our own destiny’.

I chose it because I once again saw a link between media one and my literary studies course. That very morning in textual crossings we had watched ‘predestination’, an Australian-American sci fi movie that was filmed around Melbourne and even in RMIT.

If you haven’t seen the film and intend to (and if you like sci fi I recommend you do because I quite enjoyed it), look away now to avoid spoilers. Basically, the film questions how much we are in control of our own destiny through looking at time travel and the possibility of an infinite, paradoxical time loop. Basically, the central character (who seems to be three characters at first, and then two, and then finally we realise it has been the same person all along) is born a woman, and meets a future version of herself after a sex change to a man, with whom she conceives a child, the birth of which causes her to become the man that will go back in time and impregnate her past self. The baby is taken shortly after birth, and it is later revealed that she is in fact both her own mother and her own father. Furthermore, as he (now a male) is taken back in time in the first place by a mysterious time agent who is seeking to capture a terrorist bomber, it slowly becomes clear that the time agent is another, surgically altered future version of himself and an even further distant future version is the bomber. Are we still following?

It’s complicated, I know, and to be honest bordering on the ridiculous. However, despite the fact that I managed to see every single plot twist coming before it happened, I didn’t really notice how ridiculous the story really is while I was watching it. It’s a well-told story that asks an interesting question: what if time travel were possible, and somebody used it to go back into their own timeline and create an event that their future existence depended on? Would they then be ‘predestined’ to go on to live that life, or would they have a choice, could the control their own destiny?

It’s an interesting philosophical question because at many times in our own lives – as Daniel was suggesting with this prompt – we already ask ourselves if we are in control of our lives and our destiny as a human race as a whole, or if some events must occur. As John asks Ethan Hawke’s time agent before he realises he is his future self, “Yeah, but don’t you sometimes think that things are just inevitable?” To which the agent replies, “Yes, the thought had crossed my mind.” Throughout the film, the central character is faced with several choices between what is ‘predestined’ and what he/she wants. After falling in love with his past self as a woman, and remembering the hurt he caused himself, John is reluctant to leave Jane and tries to shoot the agent, before the agent explains to him what his destiny is.

Look, it’s all very complicated I know, but it’s an enjoyable film that imaginatively and philosophically asks the question, are we in control of our own destiny?

Team project update

Sorry the posts are a bit light-on this week (slimmed down a better buzzword perhaps?), but it’s assessment time and I’m neck-deep in powerpoints about Airplane!, essays about financial rhetoric and, of course, the media one team assessment.

As I posted last week, so far I’ve done my article, and I’m hoping to complement it later this week with a twitter feed or blog roll that will hammer home our message of interactivity.

The big news since last update is that we’ve recorded our opening vlog. It hasn’t been uploaded yet (I’ll link it here when it is), but I think that it went well. The three of us (Dusty, Jac and I) recorded ourselves introducing our blog, and plan to insert video annotations to demonstrate the interactivity audiences have when looking at our site. We spoke to camera vlog-style, as we wanted to emulate the techniques of online video producers whose examples of interactive media we are exploring. It was a bit difficult to talk to camera without laughing or getting embarrassed, but we ended up with a video in which each of us took turns explaining the overall idea of the blog and what we’ve been doing individually.

Speaking of which, Dusty managed to score a cool interview with a popular instagram user that you can check out here. I’ll keep you posted for more updates; look forward to Jac’s photo essay on social media and some more interviews from Dusty.

Assessment season short post: it’s puntastic

Project update

Seeing as our lectorial yesterday was all about remix culture, which I’ve already blogged about, today I thought I’d upload an article I wrote for my group project about Twitter and TV audiences. It’s a bit long, and it needs a bit of polishing yet (it’s only a draft) but I hope you enjoy it!

It seems like an age ago that the symbol # simply meant a number; nowadays it is synonymous with the twitter hashtag, an online paper trail that links together conversations from hundreds of users around the world. When talking about the interactivity of modern TV audiences, it’s impossible to acknowledge the importance the humble hashtag has gained in allowing people to connect both with broadcast content and each other.

The very term ‘broadcast’ refers to mass communication, implying a universal form of entertainment that way uniformly experienced by a wide range of people. For the first fifty years, this was the truth of TV; even if audiences interpreted a TV show in different ways, it was still very much a one-way conversation in terms of their input into the creation of a show. Today, twitter (and social media) has changed all that. As Chris Copeland wrote in Adweek, “TV has a new love — that little blue Twitter bird.”

Stephanie Moritz in PRweek explains the “new kind of interactive TV” created by Twitter, saying that “Twitter and TV go hand in hand.” Moritz refers to the way in which audience members live, widely broadcast comments can be picked up by TV producers and in turn affect the way the show is made. While this has always been possible in slow motion (fans complaints must always be taken into consideration if a show is to be successful), Twitter makes that process instantaneous.

A simple example is that of The Block, an Australian renovation reality show that frequently shows fans’ tweets on the screen and invites them to take part in online quizzes that get broadcast at the end of an episode, the hashtag function allowing tweets about the show to be conveniently packaged into one stream. This gives viewers another level of engagement with the show that makes them feel like they are actively participating and interacting with the program.

But this isn’t complete interactivity, because it doesn’t affect the outcome of the show. A better example of this would be British comedy panel show The Last Leg, during which twitter polls are taken, fans’ joke answers to questions get read aloud and viewers have the chance to ask ‘#isitokay’ questions that form the basis of panelists’ discussions. Have a look at this example about The Great British Bakeoff:

As Moritz says, “a well-timed tweet can create an immediate buzz”, and there’s no doubt that interactive TV like this gets Hills’ audience engaged with the show; frequently he suggests humourous hashtags that trend on Twitter while the show is on air. But the importance of the hashtag relates not just to the interactivity of TV audiences to the show itself, but to each other: “viewers follow along on social media to converse with like-minded fans”, says Moritz. Twitter allows audiences to not just actively influence the content of a show, but to share, discuss, argue and bond with others with similar interests.

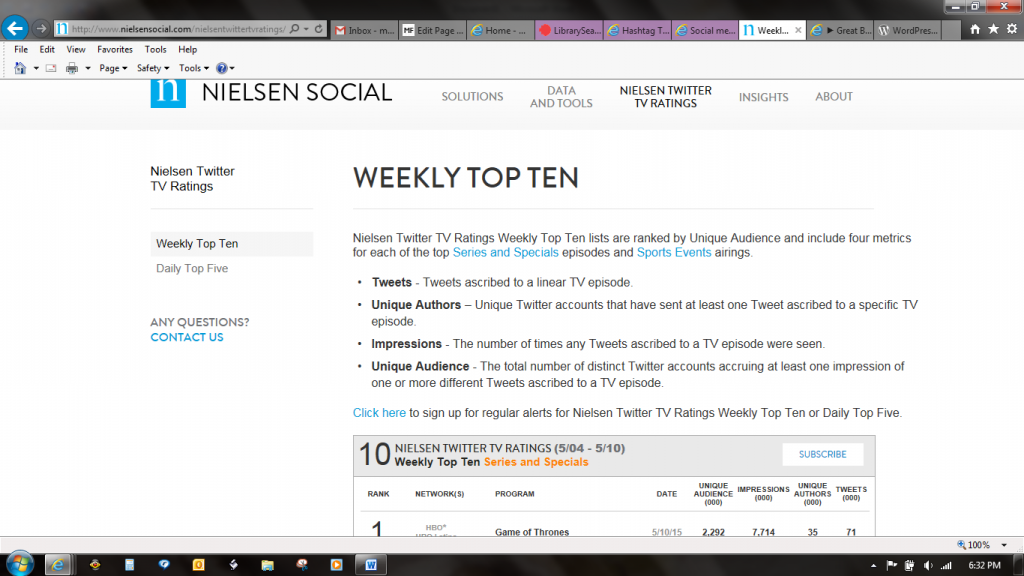

Furthermore, Twitter’s capacity for fostering interactivity has commercial benefits as well, such as more accurate TV ratings. Neilsen, who for many years have been in charge of measuring TV ratings, but have been limited by the ultimately uninformative single number that is how many households are watching a particular program at a particular time. It’s unfortunately a rather inaccurate number, as it’s difficult to distinguish between members of a household and to understand their qualitative engagement with a program. In the age of Twitter, however, Neilsen uses a set of four criteria to assess Tweets and create a new ratings system. There are a few flaws, such as the limited and specific demographic that uses Twitter, however as an accompaniment to the existing ratings system it provides valuable data about audience engagement.

However, it is important to remember that there are still many flaws in using Twitter as a tool to engage with TV audiences. Chris Copeland looks at the use of Twitter at the 2012 Grammy’s, and notices a few key difficulties, such as the sheer mass of tweets that can be created: “Since the volume of tweets (at 200,000 per minute) [during the 2012 Grammy’s] would be the equivalent of a full-length novel every hour, I’m guessing no one read every single comment made about the show.” It’s a valuable point; producers and consumers alike need to be able to filter tweets for relevance in order to be able to gain information and engagement from Twitter users. Furthermore, Copeland highlights the tendency of Twitter fans to focus on events rather than ongoing TV series, saying that “Massive watercooler moments like the Super Bowl, the Oscars or even the presidential elections are ideal for social TV . . . but it’s not there yet for social TV during the average drama or sitcom . . .” The article is a few years old now, and I would argue that Twitter users are tweeting more regularly now, but Copeland’s point is still relevant as big TV events still get much more Twitter coverage than ongoing series.

It has been argued that broadcast TV can bring us together by creating an experience that can be simultaneously shared by large populations, and the interactivity encouraged by Twitter only enhances this. As Stephanie Moritz writes, “TV is alive and social”, and we can only assume that the rise and rise of Twitter will lead to a greater and greater fluidity between TV producers and audiences

What not to buy: consumer advice

Today, I want to do a quick shout-out to one of my new favourite shows, The Checkout on ABC1.

The Checkout is all about consumer information, and breaking down myths about big-company bulldust and what rights consumers actually have. While it may not be about the media in terms of being about film or TV, it certainly discusses mediated communication, often in relation to advertising.

For example, one episode talked about the phenomenon of gendered marketing, particularly relevant to my post on colour a few days ago.

More recently, another episode discussed the advertising power of the word ‘natural’. The producers did a random survey of people on the street asking what expectations they would have of a product labelled ‘natural’. The results were unsurprising and not unreasonable; respondents said they would expect it to be organic, healthy and free of added fats or sugars. But of course, the Checkout crew found this wasn’t the case. The problem is, ‘natural’ is a very difficult word to define, which gives companies license to use it in just about any way they choose. Unhealthy, fatty, sugary foods can all be counted as ‘natural’ under the word’s vague definition.

Another great segment of the show, relevant to the advertising and photography side of media, is ‘product versus packshot’, in which footage of what an actual product looks like is compared to what it was shown to look like on the packet. Some classic examples include:

I don’t know that anyone actually expects things to look like they do on the packet, but it’s interesting nonetheless to see them side by side.

On the whole, the show is not only entertaining but provides some really valuable advice on how to avoid being screwed by big corporations. Check out the show on ABC iview or on Thursday nights at 8pm, so you can enjoy the show and so I don’t feel bad about all their stuff that I’ve embedded here 🙂

Remix

The schoolkid in me punched the air today to see that one of our readings for next week was actually a video (score!). Have a look:

https://vimeo.com/19447662

The video – and our other readings as well – brought up some really interesting points about originality that I felt linked really well to my course in literary studies.

The video above (by Kirby Ferguson) basically claims that everything is essentially a remix of everything that came before it, which is a concept we have been exploring in literary adaptations. At first, this may sound just plain wrong; surely there are plenty of stories that haven’t been told before?

That’s quite true, and to say that everything is a remix isn’t to say that it doesn’t have significant creative merit. It’s merely an acknowledgement of the fact that audiences have come to expect certain codes and conventions from media texts (see my post on semiotics for more information about this), and that most media texts will use – or ‘remix’ – these expected elements. It’s not, as Ferguson points out, a ‘conspiracy theory’, or even an attack on Hollywood originality; in fact, it’s often the adaptations of these conventions that makes a media text enjoyable.

For example, in addition to exploring direct homages and copies, Ferguson talks about adaptation of genre. Every media text that we consume can be seen to fit into a genre of some kind, and this is because of the conventions of the genre it adopts. For example, a film that ends with two protagonists falling in love would probably be described as a romance. In literary adaptations, we qualify this genre classification as an adaptation (or, in Ferguson’s words, a ‘remix’), because in adopting that stereotypical romance ending the film can be seen as adapting the storyline of every other romance film that ended the same way, from Romeo and Juliet to Twilight.

Furthermore, I would argue that, contrary to popular belief, this adaptation is not representative of a lack of originality but in fact contributes to the pleasure of engaging with a text. If the film showed the two protagonists dancing around each other for months, scared to profess their love and engaging in various catastrophic, comical events, but then ended without them getting together, I think as an audience we’d be disappointed. It’s because we’re so used to that genre’s formula that its unsatisfying when a media text doesn’t adapt that traditional storyline. That’s not to say that a film with an unhappy ending has to be unsatisfying, so much as it means it’s of a different genre. It’s this constant ‘remixing’ of existing plot structures that has led to cultural theorists such as Christopher Booker (what an appropriate name) to argue that all stories can be classified in certain set categories.

But having said all that in favour of adaptation, where do we draw the line? Where does something stop being a pleasant re-imagination of our existing expectations and start being a truly unoriginal copy? It’s an issue that’s particularly fraught with controversy when using the specific terminology of ‘remix’, so highly associated with the music industry. One of the other readings, which I personally felt was a little lengthy and irrelevant to our actual studies, nonetheless brought up the interesting idea of the impact of technology on remix or adaptation culture. Once upon a time, although you could use someone else’s idea in your own media text, you still needed to create the work from scratch. Now, technology has allowed users – from Hollywood producers to dolts like me with a decent laptop – to physically incorporate existing material into their own work.

At times, I think this can be a good thing for all parties involved. Earlier in the year, I wrote an essay for literary adaptations on the new Stephen Moffatt series Sherlock, and discussed in detail the enormous amount of fanfiction surrounding it. In addition to writing textual fanfiction, fans of the show have used graphic editing software to not only reimagine the show’s characters but to collide it with other texts. For example, there is a wide internet following of fanfiction known as SuperWhoLock, that combines the shows Sherlock, Doctor Who and Supernatural, such as this amazingly well-edited video by John Smith in which graphic editing allows two of the shows’ protagonists to meet:

I don’t think anyone can question the creativity of this work. Not only does this phenomenon of remixed fanfiction allow fans greater interaction with the show (I argued in the essay), it seems to have been well-received by the producers who playfully allude to Sherlock‘s fans in the show itself and who have suggested a cross-over episode may be in the works.

But of course there is a sinister side to this as well, especially when it comes to music culture. When artists such as Robin Thick or Colin Hay can be sued under the law for their songs merely having the same melodic structure as others, there’s no doubt that songs that actively use existing material will be held accountable as well. But is there no originality in remixed songs? I know I personally own a few Cedric Gervais remixes of Lana Del Ray songs that I wouldn’t have bought otherwise, simply because I like the remix far more than I like the original, despite their clear similarities. The remixes in question have actually sold quite well, so I can only assume that Lana Del Ray has recognised this creative input and is accepting of it.

It’s a fine line, and one that many have argued is still yet to be drawn as copyright and intellectual property law struggles to catch up with the technology that allows this new sensation of ‘remix culture’.

And considering that was my 963rd word (sorry for the essay guys!), I’m off to verify my credentials as the admin of a blog called Couch Potato. Toodle pip!

Institutionalised

Tuesday’s lectorial was all about media institutions. Having already felt sorry for the students who have this as a topic for our next assessment, I was keen to learn more, and glad when Brian started by answering the question “what is an institution?”

In doing so, he asked us to look not at media but at the institution of marriage, and think about why we would define it as such. The points brought up were interesting and really translated to media institutions:

1. Legal requirements A part of being an institution definitely has to do with legal requirements. As marriage is bound by law (both in terms of the marriages recognised and not recognised by the law), so are institutions. For example, 2011-2012’s Leveson Inquiry in the UK led to criminal charges for many involved in News of The World‘s hacking scandal, demonstrating that as an institution it is bound by and held accountable to public law.

2. Values and ethics This was an interesting one, because it is clear that marriage values are different around the world; where in the West we idealise marriage as being the ultimate announcement of love, in India it is still common and somewhat acceptable for marriages to be arranged on the basis of compatibility or even mutual familial benefit. However, it is important to note that while these values differ, they exist in all forms of marriage and thus make it an institution. Similarly, while the values of institutions differ, most have some sort of code of ethics that they operate under. For example, just recently an SBS reporter was fired after tweeting controversially his disapproval of ANZAC day. It was not his right to his personal opinion that was in question, but rather the discord between this view and SBS’s core values of tolerance and respect.

3. Representation in popular culture Think the end of every Disney film ever. Think The Wedding Singer, or Four Weddings and a Funeral. Weddings are a pretty important part of our culture and so are reflected in much of our media. Similarly, media institutions are in turn reflected in our popular culture and our media. For example, stepping away from a corporation and looking at a broader institution, journalism is a concept that is often dissected in our popular culture. From Zoe Barnes in House of Cards to Will McAvoy in Aaron Sorkin’s The Newsroom, we often see journalists on screen and an examination of what journalism is, what good journalism is and what makes it what it is today. It’s this scrutiny that makes it an institution.

4. Money Or industry, perhaps, would be a better way to put it. One of the key factors that makes an institution an institution is in making money itself (such as a corporation), or its role in creating an industry that makes money. Looking at the wedding example, while you may not turn a profit in getting married yourself, it’s guaranteed that someone is: the caterers, the venue, the dress-makers, florists, bakers . . . When it comes to media, it’s hard to think of an institution that doesn’t make money. Even not-for-profit media institutions contribute to the industry, such as RMITV, which doesn’t make money itself but promotes the media industry and launches careers of talented young media-makers. (Like me 🙂 )

Pretty in Pink

I’d like to return to semiotics today if I could, and talk particularly about the social conventions relating to colour.

A few weeks ago, I wrote a post about semiotics, after we focused on it in one of our lectorials. Basically, semiotics is the theory that discusses communication through signs, and the meaning we gain from signs. Eg, if I hold up my forefinger and middle finger in the sign of a v, you might read that as a sign for peace. There’s nothing about my fingers that actually contains the meaning of peace, but it’s a socially accepted sign that you can recognise.

What I want to talk about this week is colour as part of semiotic theory. About a week ago I uploaded a post about a poster I made for Hockey Victoria’s Women and Girl’s Round. As you’ll notice, the poster is mostly in pink and reminds us to wear pink on the day (hence my pink fingernails in the picture below). At the Women and Girl’s Breakfast with guest speaker Nova Peris, we were even given pink towels and roller balls.

I’m definitely in two minds about all this pink. As a feminist, there’s a part of me that hates the way we feel we can reduce a whole gender to a single colour, especially one that is somewhat associated with childishness and, for want of a better word, sissy-ness.

But on the other hand, also as a feminist, I love having a clear and recognisable way to celebrate women in my sport. I don’t just play hockey; I coach it, I umpire it (as you can tell from my shirt in the picture) and I’m a member of my club’s committee. I live hockey, and I’m lucky enough to be able to see first-hand the amazing skill, dedication and sportsmanship women bring to my club. However, I’m unlucky enough to be a able to understand how little respect there is in the world for women who play sport. I love that Hockey Victoria has a Women and Girls Round, and I love the idea of getting people to show their support through wearing pink.

And there’s no denying that pink is recognisably feminine, even though this wasn’t always the case. If Stephen Fry and QI are to be believed, up until the 1940s it was actually the other way around; pink was used for baby boys as it was a watered-down form of the aggressive and masculine red, where powder blue was a cooler colour and therefore suited to the girls. At some point, though, they switched, and today the colours are pretty universal signifiers of each of the genders. For example, take a look at this Huggies ad, which demonstrates perfectly the use of the two together:

And it’s not just for gender that colour has significant meaning within the world of semiotics. For example, what more widely recognised signs for ‘stop’ and ‘go’ are there than the colours red and green? And although it may be different in other cultures, in the Western World it’s still generally accepted that you wear black to a funeral.

Colours are a perfect example of semiotics; in most cases they have no literal association with what they signify, and yet our social conventions assign them meanings of their own. While this can lead to frustrating simplification of more complicated issues (such as gender), on the whole it allows for communication that transcends language and can be widely understood.

Let’s get academic

In yesterday’s tute, our group took the opportunity to pool resources for our annotated bibliography. Basically, in preparation for our assessment on interactive media audiences (working title: participation generation), we all looked at a variety of sources and summarised them in reference to their academic value and relevance to our project. I’m not going to write up too much here, because the bibliography is pretty wordy in itself (hence why I’ve only uploaded my section), but it’s pretty fascinating if you’re interested in media theory. Read it, skim it or just look at the pictures (spoiler alert: there aren’t any). Enjoy!

1. Cover, R; 2006; ‘Interactive media, narrative control and reconceiving audience history’; New Media and Society; Sage Publications (Chicago); volume 6 issue 1; pp. 139-158

I found this to be a fascinating, in-depth article that was particularly relevant to our group’s work because it focussed not just on how interactivity exists for modern media audiences but on the resistance to this interactivity, a point that I had not considered before. Cover talks about a ‘battle of control’ between media creators and media audiences, describing how some interactivity – such as using elements of a media product in another – can be dislike by media authors. I think this was a particularly unique and interesting take on media interactivity that I will make an effort to incorporate into our project as I hadn’t thought of it before. Cover also discusses the way in which interactivity has redefined the term ‘audience’, which could provide a good way for us to link our focus on interactive media to our wider subject area of audience. I found Cover’s section on the history of interactivity a little irrelevant, as his contention seems to be ‘we’ve always wanted to interact with texts but never could’, however he did cite one example that I think we could discuss in our media product, which was an SBS TV show as early as 2002 called Twentyfourseven that invited viewers to vote by SMS to determine the ending to the show. I had never heard of this happening in TV before and seeing as we were wanting to discuss a similar example from YouTube, I think this is something we could definitely discuss in our project.

2. Brennan, K; 2014; ‘Audience in the service of learning: how kids negotiate attenion in an online community of interactive media designers’; Learning, Media and Technology; Routledge (London); volume 40 issue 2; pp. 1-20

This article was a little disappointing for me, as it was not quite what I had expected and less relevant to our project than I had hoped. Nonetheless, it had some interesting points that we could use in our project. The paper outlined a long term qualitative and quantitative study undertaken by MIT, in which a website named ‘Scratch’ was started for young people to produce and share ‘projects’. This was my first issue with the paper: though the analysis of the research methods and findings was in depth I found it difficult to understand exactly what ‘Scratch’ was and the nature of projects produced on the site. It also became clear that the focus of the research was on interaction between media producers, rather than media that was itself interactive (our focus), making it less relevant to our project. However, it still had some interesting findings, particularly regarding the youth market that our focus on online media might lead us to concentrate on. Firstly, the idea of social media users being ‘audiences’, a point I had not considered before. The paper suggests that in some respects ‘Scratch’ resembles social media sites such as Facebook or Twitter, and yet describes users not as such but as ‘audiences’. The idea that your friends on Facebook become your audience when you are posting things such as videos or photos (or perhaps even voicing your opinion on an issue) was a considered and new one (I thought), and one I would look to using in our project.

3. Finnerty, A J; 2011; ‘NCM media networks and audience entertainment group engage movie audiences with the first national interactive big screen cinema game in the us’; Business Wire (New York); accessed 2/4/2015

While the content of this article was very interesting and it was relatively easy to read, as an academic resource for our purposes I have to say it is probably quite limited. The article (somewhat dated now as it was made in 2011) describes a new (at the time) interactive video game advertisement that was to be shown in movie theatres before feature films. Lasting 90 seconds, the video seats the audience next to a classic cartoon character on some sort of log flume ride, and by collectively raising and moving their arms, the audience forms one mass “human joystick” that controls the character as it moves and allows them to collect points along the way. While I found this a particularly interesting concept, I would have to suggest that the article’s credibility as an academic source is somewhat limited by its obvious (to me at least) bias. Phrases such as “the audience always wins by being among the first in the U.S. to experience the future of cinema advertising” and “this exciting new campaign” suggest to me that the article was produced by someone affiliated with the creators of the video, and thus its analysis of the impact of the video is probably limited. Nonetheless, I think that there are a few important points that our group can gain from this source: one is the idea of physical interactivity – that is, not just online discussion but actual movement that affects a piece. The second relevant point is interactivity in the cinema; generally cinema audiences are seen as being fairly non-interactive (at least in comparison to online or broadcast media), so it was interesting to look at interactive audiences from that perspective.

4. US Federal News Service; 2010; ‘Social media: presenting MCAs new river to an interactive audience’; US Federal News Service (Washington); accessed 2/4/2015

I have to concede that this was a particularly poor article. Its first problem was that it was overly simplistic and fairly unanalytical; the first two-thirds of the article seemed to be dedicated only to describing a brief (and completely shallow) history of media, which was useless from an academic perspective. I also did not realise when first selecting it as an article that it had actually been produced by the United States Marine Corps. Thus, the remaining third – which actually did discuss interactive media – focused entirely on the use of interactive media by the US Marine Corps. It was obviously biased to shed good light on this institution, and so lacked depth in its analysis of media use. However, this did not mean that it was entirely useless; while we may not refer specifically to this article in our project, it provides an interesting perspective on the industrial uses of interactive media, particularly social media. For example, the article discusses the value of social media in distributing advertising, stating that “every time a Facebook user becomes a fan of a Marine Corps page, an update is posted on their profile for all of their friends to see. This creates numerous opportunities for Marine Corps pages to reach millions; and as a Facebook page traffic increases, so does the traffic to official websites.”

5. Smith, D K; 2014; ‘iTube, youTube, weTube: social media videos in chemistry education and outreach’; Journal of Chemical Education; ACS Publications (Washington); volume 91 issue 10; pp. 1954-1959

This article was interesting to read in that it was written by a science professor, and so came not from the perspective of a media academic but from the perspective of an ordinary person seeking to enjoy the benefits of interactive, online media. The author, David K Smith from the University of York, was looking for ways to engage his students further in their chemistry units. He reflected upon popular chemistry channels he had seen on YouTube, and so decided to utilise the site in his own teachings. The article outlines not only his own creation of YouTube videos but his student’s use of YouTube to create projects that explore chemistry. Overall, the article was very easy to read and quite accessible, which kept me engaged and interested in the subject matter, but obviously its relevance to us was limited as its focus was not on a media perspective. However, the structure of the article itself and the research within it I felt was quite telling of the benefits on interactive, online video. For example, there was one section where Smith was analysing the duration of hits on his videos, as YouTube can supply the information regarding how long a particular viewer has watched a video. Smith’s use of this information to understand his viewers’ habits and in turn shape his content I thought was a very valuable insight into the value of interactive media technology, and a point that we could definitely incorporate into our own work. Smith further highlights the way in which interactivity can help producers tailor their content when he says, “the comments feature of YouTube enables a real dialogue with viewers, for example, if there are things viewers have not fully understood, want further information on, or disagree with.” This industrial value of online interactive technologies is a point that will be worth discussing in our project.

6. Dembin, R M; 2015; ‘I saw it in the lobby’; American Theatre; Theatre Communications Group inc. (New York); volume 32 issue 1; pp. 62-64

I found this to be a fascinating, well-written and engaging article. While other articles I read focused on digital and broadcast media, particularly online media, this article focused on theatre, which I thought was a really interesting format in which to look at interactivity. Dembin describes the particularly modern idea of an ‘interactive lobby’, looking at examples of when producers of a theatre show have created interactive exhibits, displays and activities for the lobby space of their theatres. These displays ranged from the traditional, such as a ‘face-in-the-hole’ painting that allows audiences to feel transplanted into the story, to more complex, modern activities such as show-specific apps and touch-screen displays for comments. I thought the idea of looking at interactive audiences not just in the online sphere but through physical, tangible interactivity was relevant to our project as it was not something I had considered and therefore something we should look into to including in our work. Dembin also brings up some points about interactivity that are relevant observation for our project as they can be transferred to other media formats; for example, he discusses the idea that interactivity can connect audiences not just to the media text but to each other: “These installations bring theatregoers closer not only to the play they’re seeing, but to each other as well.” I think interactivity of audience members with each other, as well as with a text, is an interesting extra dimension we could add to our project. I think this article will provide a valuable source of information to us as it makes good observations but is quite accessible and easy to read.

7. Lang, T; 2013; ‘Evolution of interactive print’; Target Marketing; North American Publishing Company North American Publishing Company (Philadelphia); volume 36 issue 6; pp. 23-24

This article, such as the article about the interactive cinema ad, I thought was particularly interesting because it discussed interactivity within the context of a medium that is not usually associated with it. Unfortunately, the article doesn’t actually talk much about audiences, but still creates an interesting discussion regarding interactive technologies. It discusses the technology of the ‘visual search’, a technology that allows users to take pictures of printed images and text with their smartphones or portable devices and do a web search based on that picture. It was a well-written article, and easy to read, however its lack of focus on audience limited its relevance to us. However, the focus on print was particularly interesting to me and I think something we could consider drawing on in our project. The article also had a focus on brand engagement, which I think would be particularly interesting to discuss in our project; advertising draws heavily on interactivity and interactive media in the modern world and this article could give us some point to include. For example, Lang says, “Engagement is key; it’s no longer profitable to talk at consumers with stale content. With these new technologies, marketers can truly embrace and crosspromote multiple platforms, enabling consistent communications across all touchpoints. A marketer’s dream!” Another interesting and relevant point Lang makes is interactivity across more than one medium: “So wouldn’t that [the control modern audiences have over their own media consumption] require marketers to not pick a platform – mobile/online vs. print/offline – but instead find a way to consistently communicate across all channels?” This is a point I feel we could include in our project.