In my last post, I talked about Scott McCloud’s article on ‘the gutter’, and the meaning we create to fill in the gaps in comics. I mentioned that this applies to a range of different media, and this was what we talked about in our lectorial yesterday. Guest speaker Liam Ward (RMIT lecturer and media extraordinaire) spoke to us about film editing, and he had a pretty interesting take on it. He said that while most people see editing as a way of fixing movies, he says it as ‘breaking’ movies because you create gaps in the action in which the audience can fill their own meaning.

For example, let’s say there’s an episode of your favourite sitcom in which the decidedly unsporting protagonist decides he wants to join a gym. There is a shot of him stating his commitment to his new project, and then there is a shot of him sweaty, red-faced and exhausted. We haven’t seen him at the gym, but the edit implies a passing of time that allows the audience to imagine that he has been to the gym and that it hasn’t been easy.

Now imagine a man walking down the street in jeans and a t-shirt with a backpack. Where is he going? To work maybe, or to see friends? Now imagine that shot in between the shot of the man stating he will go the gym and the one of him sweaty and tired. All of a sudden we can say pretty conclusively that the man is going to the gym.

That’s what’s called the Kuleshov Effect. It’s a film theory that states that just about all the meaning an audience gains from a shot is not actually contained within the shot but in the shots around it. This phenomenon was first observed by Russian media theorist Lev Kuleshov in the 1910s, and it makes a lot of sense. Take a look at this video that Kuleshov created as an experiment to test his theory:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zUZCPPGeJ1c

Now it doesn’t work for everyone, but most people find that the earlier shots affect the way they interpret the actor’s expression. After the soup, he looks hungry. After the child, he looks sad (or like a creepy child-killer if you ask me). After the woman, he looks lustful. The point is, the cuts between the shots and the arrangement of the shots affected their meaning.

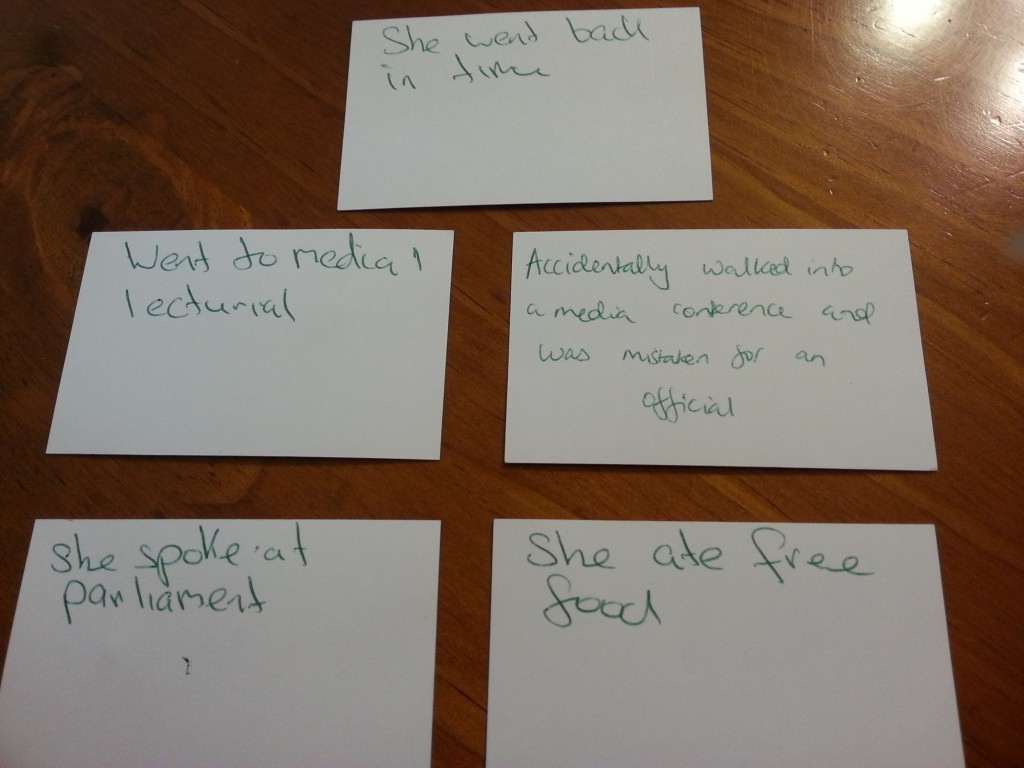

To test this phenomenon – and indeed the power of editing – ourselves, in media one we in pairs had the challenge of creating a five sentence story in which all of the sentences could be rearranged, and the story would still make sense. We worked our way up to this, but in the end this is what my partner Russell and I came up with:

It may not be the most exhilarating story in the world, but hey, you have a go, this stuff is more difficult than you might think! It was particularly interesting though to see how the different arrangement of the same five events affects our understanding of them. If ‘she got free food’ follows ‘she was mistaken for a media official’, then it implies that that’s why she got the food. But if it follows ‘she went to parliament’, it implies she got the food at parliament. (By the way if it’s seeming like a really weird story that’s because it started off with us describing our day. And then adding time travel.) While not particularly revolutionary, it’s important when looking at editing to understand how the selection, omission and arrangement of certain elements affects the audience’s understanding of cause and effect and therefore narrative. And it’s not just relevant to media but our lives in general. When you’re telling your mum about your day, “I went shopping and met a friend” is slightly different to “I met a friend and went shopping.” And that, my friends, is the power of editing.