Posts Tagged ‘COMM1073’

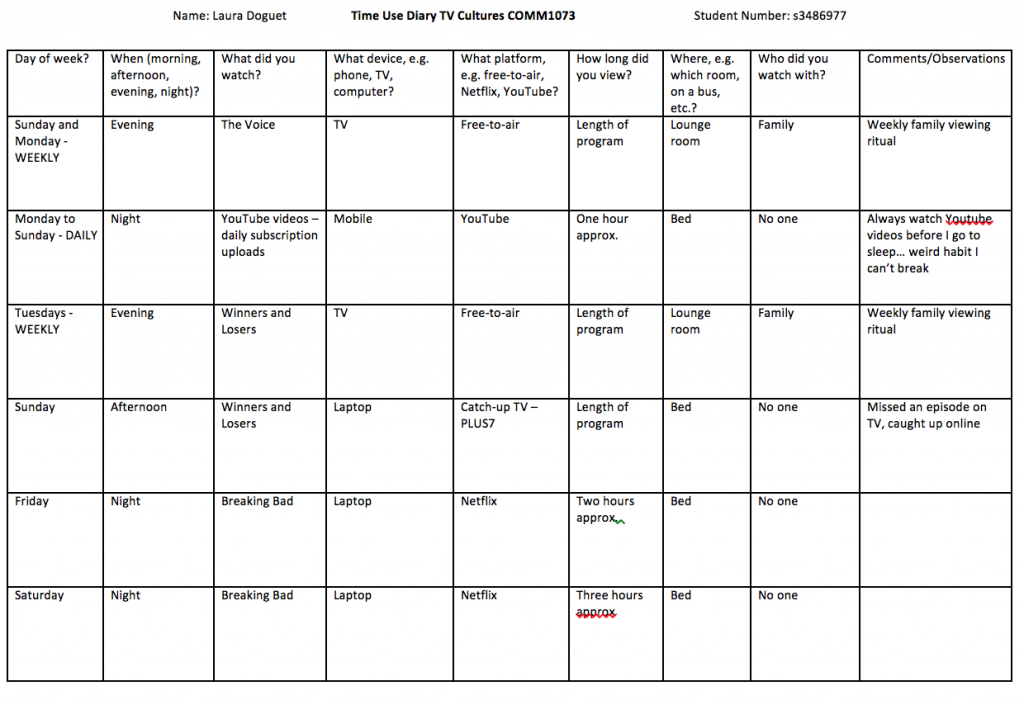

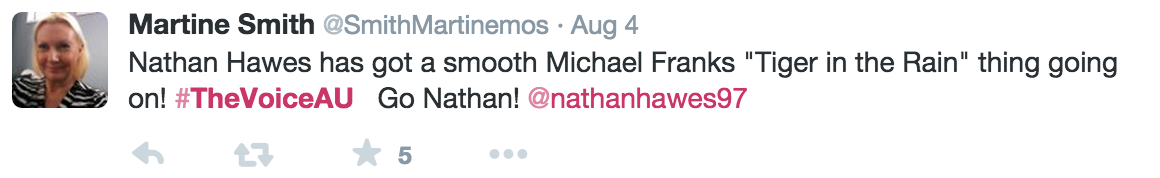

Keeping up with the time-use diary has taught me a lot about my viewing habits over the past semester. Based on the programs, platforms and devices I have engaged with, I will analyse my viewing in terms of the following four areas: YouTube in the place of TV, binge-watching on video on demand, family rituals and the power of televised movies.

YouTube is a huge weakness of mine and, as evidenced in my time-use diary, I spend more time on it than any other viewing platform. I have many subscriptions that I engage with regularly – primarily vloggers– and I find it difficult to lessen that engagement once engrossed with their channels/lives. Through the direct address of their viewers, vlogs effectively “establish conversations between the vloggers and their audience” (Aran et. al 2015). As a result of this, viewers feel connected to vloggers through them being their authentic selves and the affective dimension of their expression (Soelmark 2015). I think I also find myself spending more time on YouTube than watching TV or Netflix because watching one eight-minute video on my phone feels like less of a distraction when studying than a 40-minute episode of a TV series. However, this simply means I end up watching more YouTube videos, so either way I end up being counterproductive. Alex Juhasz describes YouTube as a “private postmodern TV of distraction,” which has proved accurate in my experience.

Binge watching is another mode of viewing which I found myself falling victim to. While I usually try to refrain from giving into the temptation during uni, I fell into a relapse over the mid-semester break as I watched a solid eight episodes of Breaking Bad in a single day (a little late to the game, I know). Lisa Perks refers to binge watching as a “media-focused floating holiday, one that affords a break from everyday drudgery through an immersive escape to the fictive world”(2014). This notion sums up my experience with binge watching as I love being so immersed in a program that you feel the need to watch consecutive episodes. Perks also notes that this mode of watching can be either motivated or accidental, and ultimately made easier by streaming services. Netflix and the like enable instant gratification as they immediately load and play the next episode before you have time to re-evaluate your life.

I also became aware of the fact that the little amount of traditional television I watch is almost always with my family. My parents and I tend to find ourselves getting hooked on two genres: Australian dramas and competition reality shows. We engage with these programs as per their weekly scheduled slot and work our nightly routines around their basis. While some scholars argue that television is disruptive to the family’s socialness, others have more of an open mind suggesting it can bring the family together and provide a topic of conversation, rather than supplant it (Morley 2005). Viewing in this sense for me is as much about spending the time with the family as it is about the programs themselves.

Finally, the last form of televisual content I found myself engrossed by was televised movies. I have a love-hate relationship with televised films as so often I wind up watching movies that I either own on DVD, or that I’ve seen many times before. For example, the other night I returned from work to find the Bourne Identity screening on Channel Nine. Despite being a quarter of the way through and aware of the fact that we own it on DVD, I persisted to watch the film on television, ads and all. While I acknowledge the absurdity this viewing habit, there is just something strangely appealing about films that are slotted into the daily television broadcast. It feels like more of a ‘special event’ than if I was to fish out the DVD or source the content online.

Evidently, the time-use diary has led to some interesting realisations about my viewing practices – the good, the bad and the questionable. It’s interesting to note the shift towards video on demand services and consequently the lessened level of engagement with traditional television. This is likely indicative of a broader cultural shift in viewing habits resultant of the evolution of viewing devices and platforms. Nevertheless, the traditional television still holds merit in the family household and will likely continue to be relied upon for years to come.

References

Aran, O, Biel, J & Gatica-Perez, D, Broadcasting Oneself: Visual Discovery of Vlogging Styles, IEEE Transactions on Multimedia, Jan. 2014, Vol.16(1), pp.201-215

Laytham, B 2012, ‘Youtube and U2Charist: Community, Convergence and Communion,’ IPod, Youtube, Wii Play: Theological Engagements with Entertainment, Wipf and Stock Publishers, p.50-71

Morley, D 2005, ‘Television in the family,’ Family Television: Cultural Power and Domestic Leisure, Routledge, p. 7-29

Perks, L. 2014, ‘Behavioural Patterns,’ Media Marathoning: Immersions in Morality, Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books, p. 15-39

Soelmark, N 2015, ‘Circulating Affect’, Structures of Feeling: Affectivity and the Study of Culture, Berlin, Walter de Gruyter, p.199-255

When we think of the terms ‘fan’ and ‘fandom,’ adjectives along the lines of obsessive, crazy and hysterical tend to immediately spring to mind. But is it necessary for individuals to align with these stereotypes to be considered a fan, and how has fan culture and the associated stigma developed with the evolution of the Internet? For the purpose of this blog post, I will be investigating the nature of media fan culture in relation to the classic US sitcom, Friends.

Known and loved by many, Friends revolves around a circle of friends living in Manhattan who face the everyday struggles of adulthood. With elements of love, loss, family and of course friendship at its crux, Friends, created by David Crane and Marta Kauffman, went on to become one of the most popular series of all time (Davies 2013). While the rave reviews and ratings at the time of the show’s inception were indicative of its success, its ability to stand the test of time to this day certainly says something about the loyalty and dedication of both its old and new fans alike.

Image source: tv.com

The term ‘fan’ refers to “somebody who is obsessed with a particular star, celebrity, film, TV programme, band; somebody who can produce reams of information on the object of their fandom, can quote their favoured lines or lyrics, chapter and verse” (Duffet 2013). Hardcore Friends fans uphold a level of devotion in line this definition: they can watch episodes over and over again and still find them hilarious, have the ability to relate every life situation to a Friends episode and quote all of the characters word-for-word.

Fandom, on the other hand, relates to the collective of individuals who hold a shared level of devotion and mutual interest towards a popular culture artefact, often likened to a modern cult following (Ross 2011). A sense of community and belonging can derive from participating in a fandom and some argue that fans are “motivated as much by the values of collective participation with others as by devotion to the persona [itself]” (Horton & Wohl 2006). However, despite the positive outcomes that result from their participation and the growing acceptance of fandom as a permanent sub-culture of society, negative connotations persist to follow in their wake. Henry Jenkins claims that fandoms are “alien to the realm of normal cultural experience” and “dangerously out of touch with reality” (2012), while Matt Hills classes them as “obsessive, freakish, hysterical, infantile and regressive social subjects” (2004). Although these are somewhat accurate representations of your stereotypical ‘Directioners’ and ‘Beliebers,’ I would argue that it is not reasonable to class Friends fans in this condescending regard. When a program is widely considered to be high quality and in good taste, it deserves to have people follow it, enjoy it and actively engage with the program and like-minded others.

While the term is perhaps more commonly used and referred to in this generation, fandoms have existed in our society since the early 1900s (Duffet 2013). It is their means of participation since the advent of the Internet, however, that have taken on new extremes and thus transformed their image. Friends began in 1994 and concluded after 10 strong seasons in 2004. For the vast length of this time, the Internet was not readily accessible and today’s most influential social media platforms did not exist. Nonetheless, the fandom found other ways to express their love for the show. For example, the water cooler effect was in full swing as fans would discuss happenings of the program the next day at school or work; individuals could purchase VHS versions of the show or DVDs when they eventually became available for additional content; or, they could engage with the occasional article and/or interview published in print media. Today, Friends fan culture has been revived and revolutionised through the integration of content across an array of different mediums online. There are social media accounts and pages solely dedicated to the program, memes on every corner, fan fiction, fan art, online quizzes and the list goes on. This proliferation of content has likely ignited a new wave of Friends fans, whilst further fuelling and satisfying the love of those who have been there from the start.

Evidently, the Friends fandom has not only stood the test of time, but they have also adapted to the changing ways of the media landscape in their expressionistic endeavours. Despite the cynicism that comes hand in hand with fandoms, Friends fans remain civil and untouched by the negativity knowing that their love for the program is justified.

References

Davies, M 2013, ‘Friends forever: Why we’re still loving the hit TV show 20 years on,’ Daily Mail, October 20, viewed 23 October 2015, <http://www.dailymail.co.uk/home/you/article-2465332/Friends-Why-loving-hit-TV-20-years-on.html>

Duffet, M 2013, ‘Introduction,’ Understanding Fandom: An Introduction to the Study of Media Fan Culture, Bloomsbury Publishing, p. 22-76

Hills, M 2004. ‘Defining cult TV: texts, inter-texts and fan audiences,’ in A. Hill and R. Allen, ed., The Television Studies Reader. New York: Routledge.

Horton, D & Wohl, R 2006, ‘Mass Communication and Parasocial Interaction: Observations on Intimacy at a Distance,’ Participations, Volume 3, Issue 1, viewed online October 20 2015, <http://www.participations.org/volume%203/issue%201/3_01_hortonwohl.htm>

Jenkins, H 2012, ‘“Get a Life!” Fans, Poachers, Nomads,’ Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture (2nd Edition), Routledge, p.9-50

Ross, S. 2009, ‘Fascinated with Fandom: Cautiously Aware Viewers of Xena and Buffy,’ Beyond the Box: Television and the Internet, Blackwell Publishing, p.127

The evolution of televisual systems and social media has not only transformed the way we engage with content, but also the social relations that exist between audiences. Instead of watching and discussing the grossing program with the family, viewers are taking to social media to start the online discussion live as events unfold. For the purpose of this blog, I will be discussing the how the social experience relative to broadcast television has changed, in particular, how scheduling and the proliferation of social media has shaped how we interact with fellow viewers of a program.

Historically, watching television was primarily a social and family-oriented event or experience. We all know the image of the typical white middle-class family spending some quality time together as they sit mesmerised in front of their one-and-only television set. While this image may seem out-dated, it still holds relevance in society today. So what is it about television that makes it such a socially unifying resource?

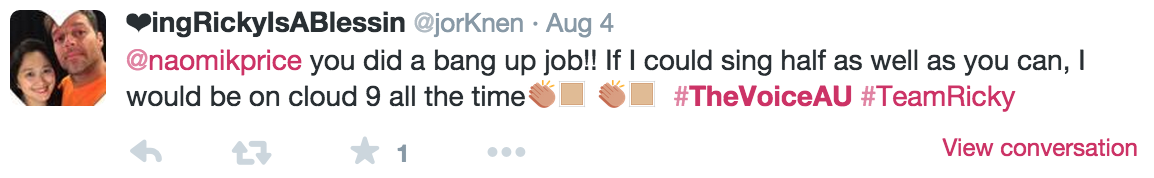

Television programs are scheduled strategically to reach their target audience at a time when it suits them. For example, in the evenings it is assumed that children and parents have returned from school and work respectively, and wish to wind down with some family friendly programs. This effectively brings the family together as the programs are timed to suit their lifestyles and also usually their mutual interests. Consider singing competition show, The Voice – one of those programs that everyone can get sucked into. Typically, watching The Voice with family or friends is a more fulfilling viewing experience than watching alone as we can commentate our thoughts and feelings on the program to those around us. For example…

“I can’t believe he or she got through to the battle rounds with that song choice!”

“OMG, I know right?”

While this remains a familiar scenario in some homes, social television has taken on new meaning with the recent proliferation of the Internet. For one thing, increased television ownership enables family members to call dibs on a TV to themselves (Singer 2010). Consequently, instead of communicating with the family, they instead take to social media via a second screen to participate actively in the live discussion with equally passionate strangers (Ingrey 2014). When The Voice is on TV for instance, Twitter and Facebook blow up as people engage with others in the viewing community about the happenings of the show.

Even if watching on their lonesome, scheduling reassures viewers that someone else in the world has watched it ‘alongside them.’ If they need to vent about whether or not ‘so and so’ deserved to win that battle, it is more than likely that someone in the viewing community will share their frustration at that moment. The imagined community – a perceived community, culture or nation of viewers – becomes more real as viewers can see the comments flood in live as the show is broadcasted (Anderson 2006). This reinforces feelings of belonging and community to viewers, resulting in a (mostly) positive social experience, albeit online.

It is interesting to note how scheduling can have such impact over our own viewing habits and behaviours, as well as how we subsequently interact with others.

REFERENCES:

Anderson, Benedict, 2006, ‘Introduction’ in Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, Verso, London, p.6

Ingrey, Melanie, 2014, ‘Triple Screening: A New Phenomenon,’ weblog post, 23 February, Nielsen Insights, viewed 10 August 2015, < http://www.nielsen.com/au/en/insights/news/2014/triple-screening-a-new-phenomenon.html>

Singer, Melissa, 2010, ‘Televisions are breeding faster than Australian households,’ The Sydney Morning Herald, July 19, viewed 9 August < http://www.smh.com.au/digital-life/hometech/televisions-are-breeding-faster-than-australian-households-20100718-10g3k.html>

Dead Set is a horror/drama mini series in which a zombie apocalypse leaves the Big Brother housemates as the only remaining survivors. Sound ridiculous? Sure. But it is a clever concept created by British broadcaster Charlie Brooker. As an avid zombie fan himself, he believes “every person in the country must’ve fantasised at some point about what would happen if some terrible apocalypse occurred during a run of Big Brother (2008).” Dead Set follows protagonist Kelly, a worker on the fictional program, who manages to save herself and seek refuge in the house of oblivion.

Image source: andykinsella.com

The show can be read in a variety of ways, but in this blog I wish to focus on the way it represents the relationship between reality TV, its producers and its viewers. While Brooker claims that the series is “primarily a romp,” he encourages audiences to be the judge for themselves. The show spoke to me as a critique against reality TV and its creators, but predominantly the culture and following behind the genre itself.

The first episode in the series begins with housemate Joplin questioning the attraction and merit of television shows like Big Brother in our society. From the get go we are thus led to question how reality TV influences us, and why are audiences are so besotted by it.

According to S. Shyam Sundar – professor of communications and co-director of the Media Effects Research Laboratory at Penn State University Park – reality TV is “much more seductive [than other types of programming] because it seems much more real, much less orchestrated (McDermott 2012).” While this is true to some extent, it is widely recognised today that reality TV is typically not a true representation of ‘the real.’ Dead Set highlights this as Kelly doubts her new job: “the show and the crowds and everything, it’s not really real is it?” This comment encourages viewers to think past what we see on screen and question the validity of what is labelled as “reality.”

To elaborate, reality TV is universally recognised as ‘trash.’ Big Brother of all shows is perhaps the epitome of this, thus making it the obvious choice of program to use as a basis for critique in Dead Set. Brooker also notes that “all zombie movies eventually boil down to a siege situation,” and the secluded, camera-filled Big Brother house would be an ideal and original setting.

In many ways, the mindless zombies in Dead Set attempt to represent and undermine the viewers of reality television. The show likens reality TV to an infection, taking over the world as it gains popularity and sucking in its victims in one by one. Once people start watching shows like Big Brother, they get addicted and cannot pull themselves away. Note the parallel to out-of-control, brain-dead zombies.

Brooker also draws attention to the flaws of reality TV production as viewers are led to immediately despise the money-hungry, ignorant producers in the fictional run of Big Brother. Presumably (and hopefully) this is an exaggerated version of what goes on behind the scenes, but nonetheless it inclines viewers to question the values and priorities of reality TV production as a whole.

Dead Set definitely leaves you with a lot to think about – from the problems with reality TV, all the way through to how to survive a zombie outbreak. It certainly is an interesting representation of some complex underlying issues of the reality genre, making for a thought provoking watch.

REFERENCES

McDermott, Nicole, 2012, ‘Why we’re obsessed with reality TV,’ Greatist, 11 July, viewed 10 August 2015, <http://greatist.com/happiness/why-were-obsessed-reality-tv>

Brooker, Charlie, 2008, ‘Reality bites,’ The Guardian, 18 October, viewed 11 August 2015, <http://www.theguardian.com/film/2008/oct/18/horror-channel4>