Aug

2015

The Social Experience of Broadcast Television: TV Cultures Post #2

The evolution of televisual systems and social media has not only transformed the way we engage with content, but also the social relations that exist between audiences. Instead of watching and discussing the grossing program with the family, viewers are taking to social media to start the online discussion live as events unfold. For the purpose of this blog, I will be discussing the how the social experience relative to broadcast television has changed, in particular, how scheduling and the proliferation of social media has shaped how we interact with fellow viewers of a program.

Historically, watching television was primarily a social and family-oriented event or experience. We all know the image of the typical white middle-class family spending some quality time together as they sit mesmerised in front of their one-and-only television set. While this image may seem out-dated, it still holds relevance in society today. So what is it about television that makes it such a socially unifying resource?

Television programs are scheduled strategically to reach their target audience at a time when it suits them. For example, in the evenings it is assumed that children and parents have returned from school and work respectively, and wish to wind down with some family friendly programs. This effectively brings the family together as the programs are timed to suit their lifestyles and also usually their mutual interests. Consider singing competition show, The Voice – one of those programs that everyone can get sucked into. Typically, watching The Voice with family or friends is a more fulfilling viewing experience than watching alone as we can commentate our thoughts and feelings on the program to those around us. For example…

“I can’t believe he or she got through to the battle rounds with that song choice!”

“OMG, I know right?”

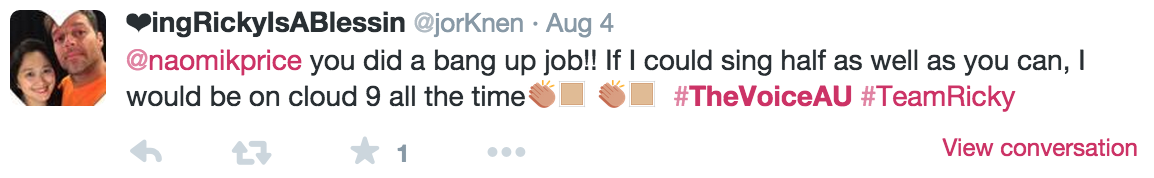

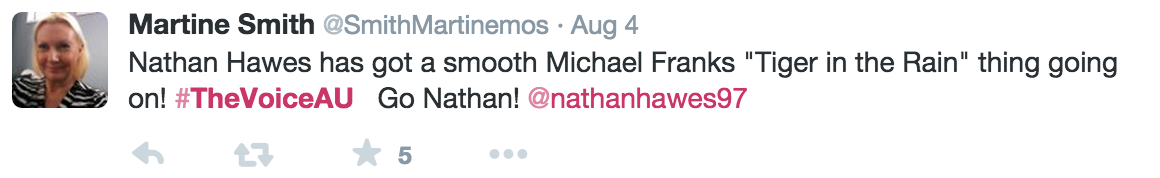

While this remains a familiar scenario in some homes, social television has taken on new meaning with the recent proliferation of the Internet. For one thing, increased television ownership enables family members to call dibs on a TV to themselves (Singer 2010). Consequently, instead of communicating with the family, they instead take to social media via a second screen to participate actively in the live discussion with equally passionate strangers (Ingrey 2014). When The Voice is on TV for instance, Twitter and Facebook blow up as people engage with others in the viewing community about the happenings of the show.

Even if watching on their lonesome, scheduling reassures viewers that someone else in the world has watched it ‘alongside them.’ If they need to vent about whether or not ‘so and so’ deserved to win that battle, it is more than likely that someone in the viewing community will share their frustration at that moment. The imagined community – a perceived community, culture or nation of viewers – becomes more real as viewers can see the comments flood in live as the show is broadcasted (Anderson 2006). This reinforces feelings of belonging and community to viewers, resulting in a (mostly) positive social experience, albeit online.

It is interesting to note how scheduling can have such impact over our own viewing habits and behaviours, as well as how we subsequently interact with others.

REFERENCES:

Anderson, Benedict, 2006, ‘Introduction’ in Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, Verso, London, p.6

Ingrey, Melanie, 2014, ‘Triple Screening: A New Phenomenon,’ weblog post, 23 February, Nielsen Insights, viewed 10 August 2015, < http://www.nielsen.com/au/en/insights/news/2014/triple-screening-a-new-phenomenon.html>

Singer, Melissa, 2010, ‘Televisions are breeding faster than Australian households,’ The Sydney Morning Herald, July 19, viewed 9 August < http://www.smh.com.au/digital-life/hometech/televisions-are-breeding-faster-than-australian-households-20100718-10g3k.html>