Norma Salvador has been in the nursing industry for over 20 years. From her confrontation with death and the possible future of nursing; she shares the vulnerable human condition that nurses balance with on a personal and professional standard.

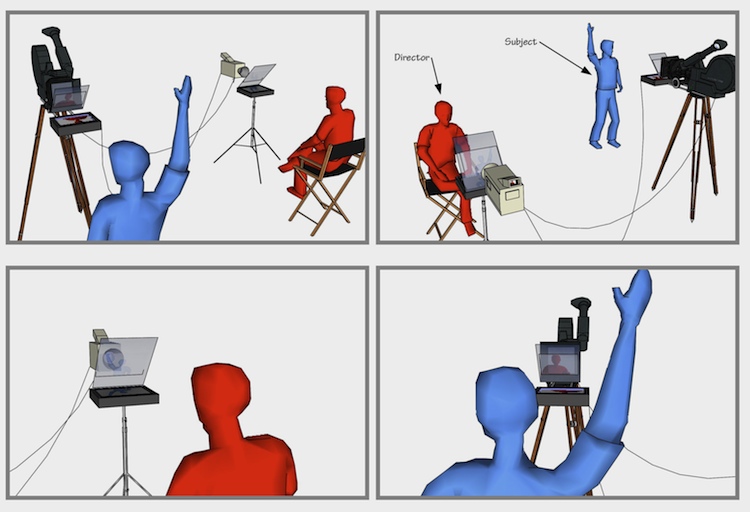

A Sony X70 and lapel microphone were used for the interview while a Canon 7D was used for filming the b-roll footage.

Edit 1

Edit 1 for Standard of Care was the longest and most gruelling edit of them all if I were to be completely honest. Condensing and cutting away 15 minutes’ worth of footage, especially most of the ‘um’s’ and ‘uh’s’ into just over 2 minutes took way longer than expected. The interview itself is cut down into a progression that concludes with her sounding advice to other promising nursing students.

In the beginning, the viewers are confronted with a story about how she experienced the death of her first patient – at this stage the viewer knows nothing about this woman and are immediately hooked with the shock of the taboo subject of death. Combined with this opening is a b-roll of a lowering heart beat monitor followed by a woman setting up an IV without her face showing and then cuts to a doll lying down on a hospital bed from the corner of a hospital window. As she introduces herself, the mystery is unveiled and humanises Norma to the viewer as a nursing facilitator who has been in the industry for over 20 years.

As she continues to talk about this relationship between patients and their families with herself, the viewer is given a glimpse of Norma at a lab demonstration of what occurs when checking for a patients vitality levels and to a short montage of what occurs when resuscitation is needed.

During her explanation of technology on the nursing industry, I decided to focus the interview entirely on her so the viewer can be more invested in this future that could potentially affect them as future patients.

Her final words are straightforward in that nursing is not for everyone as it is a passion and is then matched with a b-roll of her current position as a nursing facilitator. Her passion and hard work has led her to teach about her passion.

Re-watching this as a YouTube video, I noticed that there were a lot of cuts that didn’t match the background music, but managed to keep up with the pace of Norma’s fastening responses. Although it juxtaposes the pace of Norma’s responses, the background music complimented the tone of the piece well and managed to not outshine the b-roll in any way.

Edit 2

Unlike the first one, the editing process was not so lengthy. However, the challenging part was to incorporate a different focal point within the interview. I noticed that the interview itself is quite dense and deep for a viewer to digest and understand, so I managed to cut it down to by about 10-30 seconds to get straight to Norma’s point without any rambling or repetition.

In saying so, it is an interview on YouTube that if a viewer were to miss a point she makes, then they’re able to fast-forward or rewind as many times as they wish. Through the use of b-roll’s I decided to focus on visual representations to provide association to such an intense topic.

As Norma recounts her first encounter with death, a montage occurs. A close up of her clenching hands rubbing her wedding rings, a close-up of her eyes blinking immediately cuts to a birds-eye view of the city to set her location and also represent the fragility of life.

A b-roll is featured again at the explanation of how nurses support their patients and families throughout the emotional preparation of a patient’s death. However, the b-roll features a compilation of plants and flowers that are featured throughout Norma’s office environment as a reminder to the audience that even the nurses are even affected just as much from a personal and professional level throughout the heavy process that reminders of hope is uplifted throughout the office space.

The final b-roll sequence showcases a montage between Norma working as a registered nurse to working as a nursing facilitator to represent how Norma worked hard as a nurse to provide that standard of care to her various patients’ while also teaching her knowledge and expertise to the next nursing generation embarking that oath to provide high standards of care. Furthermore, she mentions the importance of how theory knowledge translates into real-life practice – something that still continues to abide by as a teacher.

Edit 3

It was difficult to not being able to film Norma teaching a class but then realise it was unnecessary within the context of the interview. This third edit incorporates elements from the first and second edits after re-watching and nit-picking each section within them. I managed to create a hybrid, and honestly, a better rough cut of the interview. This third edit definitely encapsulates Norma’s passion and challenges she faces as a professional that inevitably affects her on a personal level.

I decided to utilise the shorter cut of the interview while her passion for nursing is at the forefront. A short montage introduces the interview to somewhat recreate a semi-flashback of the death of her first patient with the blinking of her eyes, followed by an image of a cemetery.

In this version, a b-roll is incorporated during her explanation of how technology affects nurses in the future. This is visualised through found footage of the Vietnam War nurses transitioned to footage of Norma setting up an IV. This demonstrates how technology has changed over the years but the empathy of good nurses has never hindered.

Similarly to the second edit, the importance of human emotions in treating patients is emphasised through the compilation of plants within the office area as Norma appears to concentrate on continuing with her paperwork.

To conclude the video, Norma during the interview appears as if she is answering the viewer on a personal level and acknowledging the importance of sticking to your morals and values to provide the best standard of care for the patient’s dignity and for their loved ones.