After watching the documentary ‘The Decisive Moment’ featuring a reflective monologue by the father of street photography Henri Cartier-Bresson (who I will shamefully admit to not knowing before this class), I became inspired by his philosophy of awareness, presence and sensibility, where you “don’t think [but] act!” (Analogish 2016).

Bresson’s style of photography lends itself to natural occurrences rather than posed images, and in this sense, he is not trying to push a point or create a static meaning; it comes by itself and can be evoked by the person viewing the image.

He prefers to photograph a person in their natural environment when capturing portraiture and prefers to be in the moment with his subject (either in complete silence or establishing questions to provoke reactions).

Due to the limitations of photography and technologies, Bresson’s works were shot on 35mm film in black and white. This is a convention, as the people and places captured were living in colour, however we as an audience are viewing the images in black and white.

In the documentary he discusses the idea of the first impression being the “most important” (Analogish 2016) when capturing images, and in this sense no two images are alike, nor can they be recreated. This focus on movement and capturing moments in time rather than staging an instance is where his ‘street photography’ title defined his style.

Bresson was not interested in documenting, despite having taken some iconic images of the changes that would take place in post-war torn colonial countries such as Japan and India, where according to Bresson these places “pulse with interest” (Analogish 2016), his methodology and approach without context to the photographs would make them seemingly appear as ordinary imagery, in spite of their cultural and iconic significance.

Hokkaido, Noboribetsu, Japan, 1965.

Honshu, Japan, Farmers demonstrating against the US Army drill on their lands, 1965.

Tokyo, Japan, a farewell service for the late actor Danjuro held on November 13th 1965 at the Aoyama Funeral Hall (according to Shinto rites), 1965.

What I find most interesting is his unwillingness to be labelled a surrealist photographer despite this distinct theme running throughout his works. He would prefer being described as a photojournalist.

As stated in the Week 5 reading, legacy or hallmark photography was once seen as “absolute material accuracy” (Price & Wells 2015, p 15), as photographers were limited by resources and didn’t have the affordance of digital photography, where if connected to online storage ports such as iCloud or Google Drive, the amount of photos people are able to produce is limitless. In this sense, unlike Bresson’s confinement to 24 photos, there is no constraint.

Who is the practitioner (what is their name?) and when were they practicing?

I have chosen to analyse “photojournalist and cultural observer” Chi Modu, a Nigerian born and New Jersey raised photographer who is responsible for creating some of the most iconic images in hip-hop and infamous for documenting the ‘golden years’ (late 90’s) of hip-hop in America. Modu, like Bresson, doesn’t consider himself a “hip hop photographer” and believed that he just happened to photograph what he was motivated by.

Chi Modu in Soho, 2018.

“I’d been shooting documentary style photography and realised that someone needed to apply the same seriousness of photojournalism to shooting rappers.”

With the photo or video you are examining when was it produced (date)?

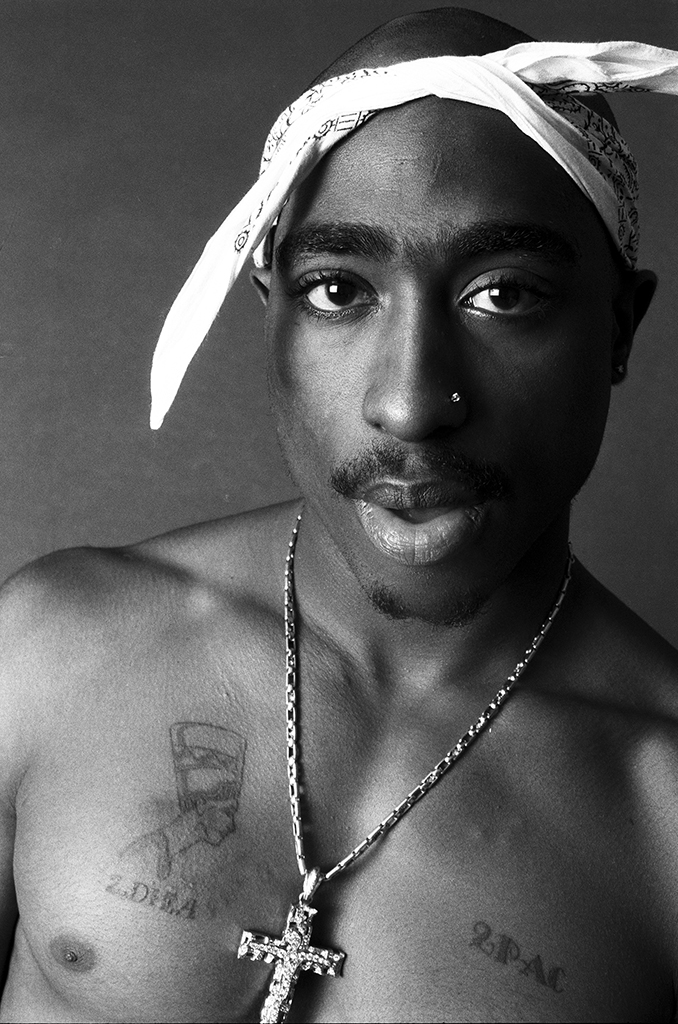

This image of rapper Tupac Shakur was taken in 1993 and shot in Atlanta, Georgia. This photo was a part of a series of images featuring the artist in front of a navy screen in the rapper’s Atlanta home.

How was the photo or video authored?

It is unclear what medium Modu used for this particular image. Similarly to Bresson, Modu likes to capture moments in his portraits rather than staging a pose, action or expression. Black and white photography in portraiture was his specialty as he was able to balance the light and contrast backgrounds and shadows to create depth in his images. This worked especially well for hip-hop artists who were often unpredictable when placed in front of a camera. This style of photography emphasises the West Coast gangster rap/thug complex of rappers during this era.

Raw film, Tupac Shakur, 1993.

How was the photo or video published?

Chi Modu mainly used print media to distribute his works, and has recently uploaded an online gallery featuring his works on his website. More recently, he has also utilised social media to reach a wider audience. His Instagram page features never before seen photos, throwbacks and captions which often include information about artists and images.

Chi Modu’s ‘Uncategorized’ installation at the HVW8 Gallery in Los Angeles, California.

Snoop Dogg released his ‘Neva Left’ album in 2017, with cover shot by Chi Modu (original image shot in 1993).

How was the photo or video distributed?

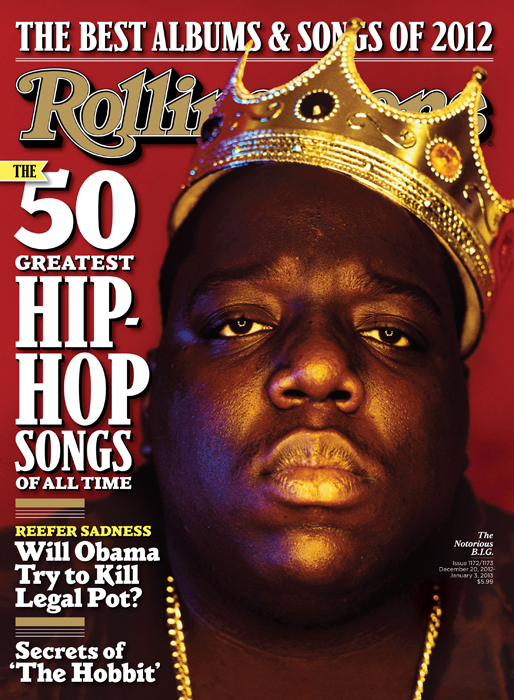

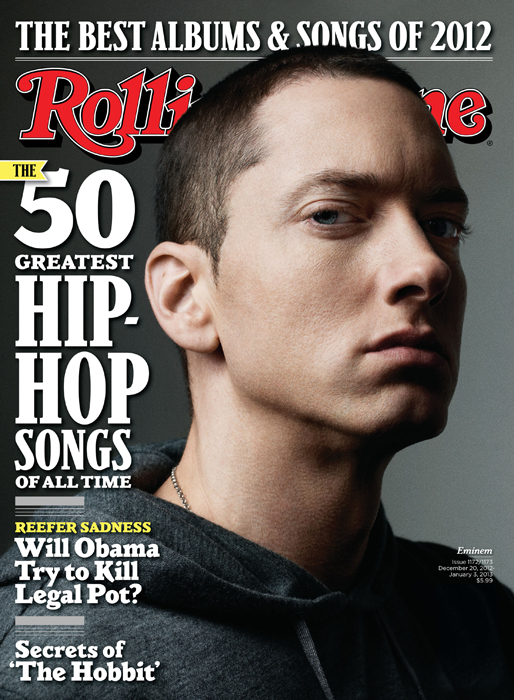

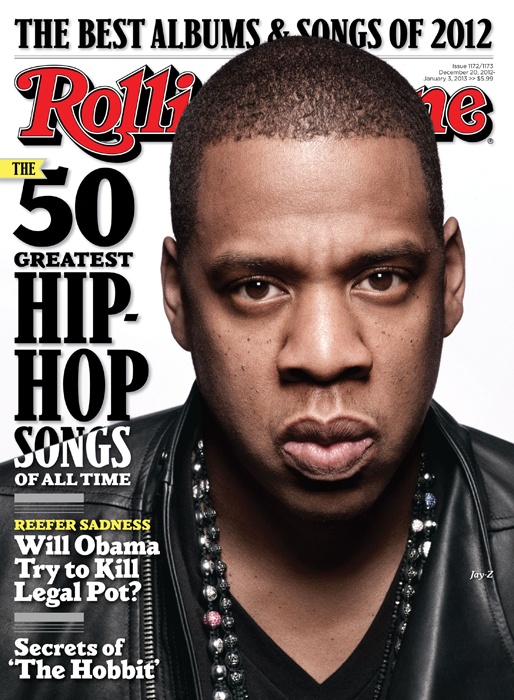

This image became the cover photo for the January 2013 rolling stones cover for the 40th anniversary of the brith of hip hop. It was 1 of 4 covers which were released to honour the 50 greatest hip hop songs of all time. The other artists featured included Notorious B.I.G, Eminem and Jay Z.

References :

Analogish, Henri Cartier-Bresson – The Decisive Moment, Vimeo, viewed 3 September 2018, < https://vimeo.com/178360907>.

Price, D & Wells, L 2015 Photography: A Critical Introduction. 5th ed., Routledge, New York

http://www.chimodu.com

http://pro.magnumphotos.com/Catalogue/Henri-Cartier-Bresson/1965/JAPAN-1965-NN145319.html