The studio was for me a great opportunity to expand my own creative practice, as I even though I’ve written a lot of fiction before, I’d never attempted to write a screenplay previously. The topics and exercises we covered in class brought up a lot of interesting points in regards to the unique affordances of screenwriting and visual storytelling. A main point that stuck out for me personally were discussions of the function of a screenplay – this being its intention to become a film – and that therefore everything in a screenplay must point toward this, like the emotions of a character must be shown audio-visually, which creates a more unique challenge when compared to writing for a novel.

For my final project, I was drawn to the creation of a screenplay for a short animated film, because I was drawn to the affordances of animation as a medium when compared to other types of films.

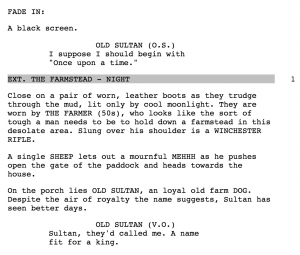

One of the main decisions I struggled with was whether to include narration or not. Since I was adapting a fairytale, and narration is a standard trope in the telling of fairytales, and it was present in all of the short films I was inspired by. But I was concerned that it might lead to be too much of a narrative crutch and a shortcut instead of actually using audiovisual storytelling. Ultimately, I decided to include both narration and dialogue but in limited amounts. The narration took the form of a voiceover from the titular character, which I decided to write in a style inspired by the film noir genre, as this worked on more than one level. It created a relationship between the generally dark themes of film noir and my screenplay, so that the dark themes in my own story feel genre-appropriate. This also allowed me to play upon the genre conventions of fairy tales as well – the screenplay opens with the voice over “I suppose I should begin with “once upon a time,”” spoken by the lead character. This acknowledges right of the bat that the story is based on a fairy tale, but expresses reluctance: it is not your typical one.

This was the first time I had ever attempted to write a screenplay, and though at first I was daunted by it, mainly because the formatting seemed so difficult to master, once I settled in to start writing I actually found it very easy and really got in the zone. I think because I am naturally a very concise writer to the style of screenwriting is well suited to me, compared to writing flowery prose. I feel that I improved a lot within this studio, which is pretty obvious when comparing an early draft of my screenplay with a later one:

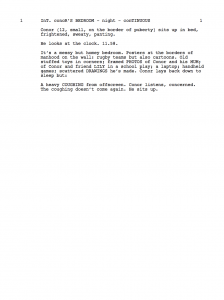

Excerpt from early draft.

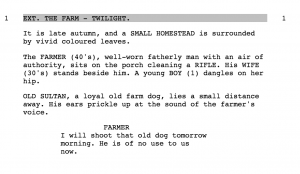

Excerpt from later draft.

This is the first scene of the screenplay, and I think the later draft functions much better as an opening, as it opens with action and character (the farmer walking), and foreshadows the coming violence (the rifle) is therefore much more engaging. Also, the dialogue in the early draft is not very refined – its simple exposition and I think I found ways to convey this information more subtly in the final draft.

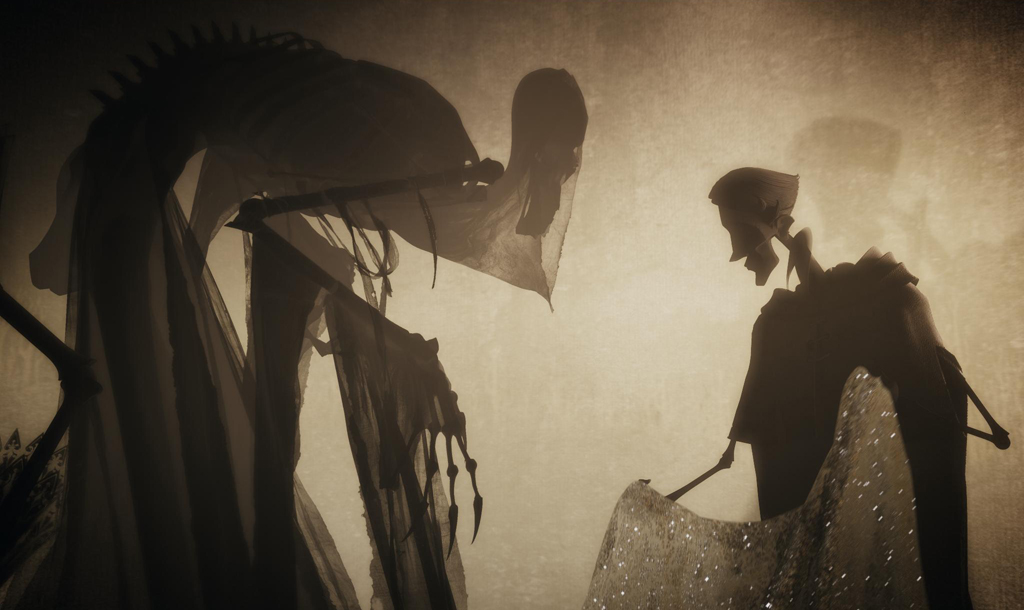

Though I am happy with my final screenplay, one thing I think I struggled to do is really take advantage of the medium of animation. The screenplay could quite easily be adapted just as a normal short film. I tried to add descriptions that would give an animator or art director added direction, like “an exaggerated roaring fire” and “a high-contrast scene.” Though to give more clarity, I added a note at the beginning of the screenplay that the screenplay is intended for an animation, and some notes on the style, and hopefully this will allow the reader to visualise the action as an animation specifically.