If you go to submit your essay and the link provides a “Form Not Published” error, you are looking at when not logged in to Google with your RMIT identity. You need to be logged as a RMIT student. Why? Because I don’t want a form filled with rubbish from every dill on the internet. And also it automatically collects your RMIT name which is a simple way to confirm that you are you.

Category Archives: noise

Korsakow Build Our Own FAQ

Have added a new menu to the blog (Korsakow) with lots under it. Including a form page where you can ask for tech help around Korsakow. What is asked there will be posted to the blog (once I have some I’ll add a menu), and if you answer them satisfactorily you will receive ‘payment’ of one mark. The mark is simply added to whatever total you get for the rest of your work in the subject.

Money and the Greeks

The Korsakow film that was mentioned in the symposium today by Florian Thalhofer: The Money and the Greeks.

K-Films

Axel writes about Almost Architecture, a substantial K-Film about signage and the city (Matt Soar has a research interest as a designer in signage and collects the old building signs of Montréal), noting the importance of use of the soundscape. Sound, in my experience, is one of the things that is often overlooked but makes an enormous difference. Prani looks at Bear 71, a high end interactive documentary that does an intriguing mix of data, location, and ecology. Imogen meanwhile explores two interactive documentaries that aren’t made in Korsakow, seeing what sorts of things are done, being done, and what they’re about and how. Henry watches two student works and is impressed, one is an abstract consideration of collage and time, the other uses a simple, repeatable premise to make an intimate observational work. Natalie has some good comments and observations about another student film -these are great models of what you need to do for the short essay. Axel wonders about themes and consistency in some of the works viewed (good questions), and the importance of the interfaces designed and used.

Intermedia Art, Lost Leaders, and Korsakow: An Interview with Matt Soar | media archaeology lab

This is an interview with Matt Soar about a current Korsakow film he’s working on, as well as Korsakow more broadly. Well worth reading to thicken up how we can understand what Korsakow does, is for, and how.

Intermedia Art, Lost Leaders, and Korsakow: An Interview with Matt Soar | media archaeology lab.

Lives, Stories, Narrative, Teleology

You can narrate your own life, but you do that after the fact, not during it. Just as I can narrate a football game after the fact and now infer an narrative arc, and even intentionality. However, while living my life, and even while playing the game, I am not narrating. This difference is important (in relation to understanding what narrative is, and is also the foundation of ethics) because one is always happening now and the other, even with our grammatical tricks of using the present tense, is always was. It is easy (and trivial) to infer causation afterwards, even where the causation is wrong, and causation is the heart of narrative.

The second problem arises because it makes my life the centre of how I want to think about narrative, and then there seems a small step to thinking that narrative equals the world, and if it can’t be narrated then it either can’t be understood, or doesn’t matter. This could be as simple an issue as using ‘me’ as the measuring instrument for the discussion (my life is a narrative). We can narrate anything we like about the world, but this is not the same thing as what the world is. This is similar to my point that I can narrate the ‘story’ of the match, but this is not the same thing as what the match is. To make it blunt: I can narrate sex, but I think you’re an idiot if you think that is the same thing as experiencing sex or what sex is (or love, hate, anger, joy, hunger, being drunk, coffee, blue, the sky the other night, a lover’s touch) – though it would our lives much less complicated.

In a story everything happens for a reason. Everything. The reason is to progress the story to its resolution, to what we call ‘closure’. Realist stories (and the definition of realism) is to make this highly artificial model appear natural, so that it relies on coincidence and character and various ways of representing itself (e.g. hiding the fact that it is a made up thing) so that things appear ‘like’ life. But unless you think you live in the Truman Show, our lives bear virtually no relation to stories in this sense, every day they are full of real accidents, coincidences, and, well, life. For instance, in a story, you only get sick for a reason (they’re bad, it’s a moral reflection, the story wants to consider mortality), in the real world we get sick because of ‘reasons’ but these reasons are germs, bugs, malevolent cells, etc, not because I want to consider mortality – just as many ‘bad’ people get cancer in the real world and die as ‘good’ people, it’s an unusual story that does that.

Implied, Intended, Real, and Narrative

Correction and Update: Thomas Hatchman asked the tenacious questions, link corrected below!

Good questions and tenacity in today’s symposium from, I think Tom (and apologies if I’ve got the name wrong). I think the conversation was the idea that all is narrative, versus my contention that all is not narrative. To try to simplify, we can narrativise anything (there was a moon who fell in love with a star, the star did not feel the same way, so the moon became sad) but that is not the same thing as saying that everything is narrative (the moon ‘looks’ sad to us due to the sun’s reflection in concert with its craters). Our lives are a case in point. Stories are cause and effect narratives that, significantly, are teleological. This means they are ‘end directed’ or defined. Things happen for purposes in a story – if a train is late in a story it is because this will let two characters meet, an accident be avoided (or not avoided) and so on. It isn’t just late. If my train is late on the way home tonight, then alas it is just late. There isn’t some final cause in relation to me which is the reason why the train is late.

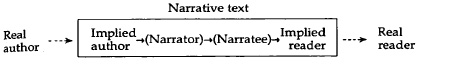

Also briefly touched on intentionality. This is also mentioned by the next reading by Ryan, but this drawing from Seymour Chatman might also help:

(Chatman, Seymour. Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1988. p. 151.Print.)

A narrative/story always has an author, as an intended statement/thing there is a real author (maker/creator) as well as an implied author within the work, while the narrator is a narrator present in the text. If they are not present there is still a sense and existing narrative voice that is a product of the text (which is why they are not the same as the real author).

Brief Videographic Moments (A Shot Is One Idea)

One thing the teaching staff will discuss in the coming week is whether we’ve noticed any changes in how things are being filmed. In my own class there was quite a difference between week two and week one, with the material much better.

When you’re filming like this, where you have at best 10 seconds, a good way to approach what you’re doing is to think of it as about one key idea, or about one thing. This doesn’t mean it might not have several shots, or move, but if it is about that object then make it about that object. If it is about light then don’t also make it about camera movement – unless the camera movement is how you make it about light. To use that last example. I might track/pan across a light, moving from dark, to burning light, to dark. Here the movement is used to make the clip address the idea of light in some way. However, if I film the light, and then move closer, then back a bit, then twirl around it a bit, the risk is that the movement gets in the way of what the shot is about, and comes across as indecision or insecurity – that you’re not comfortable with 6 or 10 seconds of just that light. Relax about the busyness, think of one shot as one idea, what you want that idea to be, and do it. Repeat if it doesn’t work.

Vanity Moment

Interview with my about using Korsakow in teaching. Vanity aside, it might be useful as it provides an overview of what and why we are using Korsakow and what a subject like this does (rather than worrying about what it is about).

The Living Documentary | MIT – Docubase

Sandra Gaudenzi (an author we’ve already read) with an interesting curated look and commentary on what she’s describing as ‘the living documentary’, part of a larger MIT project that is building an online database of documentaries….

Symposium 03 Questions

Hot out of the class (Tuesday 2:30) are the following questions (they were voted on in order of significance – those that missed out on a vote have been left out):

- Why has reality TV become so popular? Why is it that we are so interested in seeing ‘real’ lives on TV as well as stories?

- Have we lost Habermas’ notion of the ‘public sphere’ with the widespread use of mobile technologies?

- Is there a chance that the accessibility of media nowadays ruins film making instead of ‘liberating it from the old’?

- Most of the content uploaded online is never, or rarely, viewed, and receives little recognition. How effective are online sharing sites such as YouTube as a distribution network?

- What does Sørenssen mean by the ‘democratic potential of these media’? How can media be democratised?

- What is the key factor for emerging media to become as monetised or popular in that it will become the norm for all society? What is its appeal?

- Why does the corporate dollar constantly contribute to the swaying of new media towards the ‘elite’?

- Why does Astruc matter to interactive documentary?

- What does Sørenssen mean by partial public spheres? How does the public sphere fall victim to a dominating media structure?

Alexandre Astruc

Some related stuff to Astruc, who’s essay has been very influential. Two different translations, one from the US, the other from a blog that seems to be about French cinema (“My Gleanings”). Then a post by David Tames from 2010 on a major documentary site that does a nice quick job of moving from Astruc to now – Cinema Will Eventually Become a Flexible Means of Writing.

Symposium 02 Examples

The two excellent examples Seth raised today in the lecture:

MIT’s Moment’s of Innovation, which is about how documentary has always innovated around technology and showcases some recent digital examples.

And then the rather lovely The Johnny Cash Project.

For my money Moments of Innovation is really interesting if you think of it, in itself, as a documentary, rather than something that is just reporting about documentary. And again while you might think The Johnny Cash Project is about participation it is also remix, data visualisation, interactive. Trying to fit it into a primary ‘type’ commits what we call a category error.

On a related note, think about what Seth said about Google, YouTube, and analytics (tracking and analysing all the use data around a video or user). This is an example of YouTube paying attention to what a video does, rather than what it means. In spite of themselves this is a system that sort of ‘gets’ that meaning is secondary to what these things do, and that their data driven approach is not about what these things mean, but, in the small specific language of a network, what they do. Just interesting.

Perhaps.

Symposium Notes 02

Today’s discussion about taxonomy and classification and analysis. And that weird botany example. Let’s rewind and do it all again. In botany we have species. Species are different types of plants, so for example we have over 700 species of gum tree in Australia. What defines a gum tree as belonging to one species or another generally consists of differences amongst bark, leaves, and most importantly flowers and gum nuts – the reproductive parts. Historically someone comes along, reckons that plant there is new, grabs a specimen, writes a very detailed description of it, and that becomes the benchmark for that species. Once another one is sufficiently different, it is a new species. What counts as ‘sufficiently different’ is, though, a point of debate. What the debate is doesn’t matter. What matters is that it is debated because there is not this simple ‘flick’ or ‘difference’ between species, but that there will always be examples where an individual will have some of the qualities of one, and some of the qualities of others. It is a graduated scale, analogue, not discrete and digital. Now, what matters is not whether this is a new species or not, what matters is to recognise that gum trees all vary and so what matters is the extent of the variation, not the fact of variation.

All classification schemes have to do this. They have to invent a boundary or rule that says ‘these qualities or attributes mean you are a part of this group’, and so by definition if you don’t have these then you’re either out, or in another group. Where that boundary sits is always an argument informed by power (whether this be politics, authority, evidence), so it isn’t neutral (which means it isn’t only about the things we are classifying). But this system also creates for us an understanding of the world where things live in particular categories, whether gum trees, dogs, gender, bodies, or interactive documentaries.

The risk and danger then with a taxonomy is that when you build your system what you take to be the ‘specimen’ becomes a centre, and distance from this centre comes to define difference, but why is that specimen (that particular documentary) the centre rather than another one? Similarly, what comes to matter is how that documentary is like what the taxonomy identifies, which risks not seeing, or noticing all the ways in which that particular documentary has other qualities, attributes and abilities too. It creates a world of boxes, when the world isn’t actually boxes. Of course everyone who uses these classifications will tell you that this isn’t the case, that of course the world is complicated and messy, but, well, this is useful as a method and what else can we do? It might be useful as a method, but a method, not the method. As I said today a more interesting approach, certainly right now, is to look at individual works and systems and software platforms and services individually and specifically in relation to what they are. ‘What they are’ is code for what they can do and what they do do. Not what they mean, that comes after, but what they do.

Why? Well as I outlined in the symposium, if I look at a person I can use large scale things (taxonomies) to make some crude assumptions, but that’s not a good way to understand who that person is. To understand the person I need to pay attention to them, to what they do, and then I can worry about or try and work out what that might mean (for you me). If I don’t then I fall into large categories that at best become stereotypes. The difference is significant and lets me build things (arguments, ideas, even taxonomies) from the bottom up. What things do is right now more interesting than what things mean, if only because when we go straight to what they mean we risk missing, not being able to see, what the things are – which surely is the point of classifying them in the first place. So the method I’m proposing is to begin from the understanding that everything varies, and to make that a first principle, rather than identifying what things have in common and making that our first principle. It’s about recognising a world of difference, change, movement, and variation as given and that taxonomies are (false) moments of imagined stillness.

Symposium 02 Questions

The Tuesday 12:30pm class have put their collective enquiring minds together to bring these questions as the prompts for the panel next Monday (11:30am in 80.10.17).

From the Hight reading:

1. Documentary as a ‘project’ in regards to definition is becoming very broad – so, does it need to be redefined or broken up into categories? Does a taxonomy of definitions need to be created?

2. (p. 4) “The second dynamic is the appropriation by digital platforms of aspects of documentary’s discourse and aesthetics, refashioning them especially within participatory online cultures.”

How do documentary practitioners work with participatory contributions in regards to copyright and intellectual property?

And then from the Aston and Gaudenzi reading:

3. In regards to understanding the four categories of interactive documentary – How are they important independently, or should they complement each other?

4. (p.126) “..different types of i-docs demonstrates that a variety of i-docs is already established, and that each of them uses technology to create a different interactive bond between reality, the user and the artefact”

How exactly are these relationships formed using different technologies? What connections can be made between different types of i-docs in regards to how they use technology?

5. (p. 131) “He referred to the 90-0-1 principle, as cited by Jacob Neilsen (2006), which suggests that there is a participation inequality on the Internet with only 1% of people creating content, 9% editing or modifying content, and 90% viewing content without actively contributing.”

In regards to updating this evaluation – how have these statistics and practices altered with developments in social media since 2006?