Have added a new menu to the blog (Korsakow) with lots under it. Including a form page where you can ask for tech help around Korsakow. What is asked there will be posted to the blog (once I have some I’ll add a menu), and if you answer them satisfactorily you will receive ‘payment’ of one mark. The mark is simply added to whatever total you get for the rest of your work in the subject.

Monthly Archives: March 2014

Money and the Greeks

The Korsakow film that was mentioned in the symposium today by Florian Thalhofer: The Money and the Greeks.

Constraint 05

Relations. A film image by itself says a lot, but in many other ways it is quite mute. That Vine clip of a coffee cup, playing as it does with the autofocus and autoexposure of the iPhone’s camera, shows a particular cup and saucer and spoon with particular qualities. It is all description (notice the texture, hue, and light on the surface of the saucer, it’s tone, shape and the shadow). But it doesn’t ‘say’ much – it isn’t really yet narrating anything, it’s simply a coffee cup, saucer, and spoon. Add a title, and make that a part of the work (in this case “glow to orange”) and things change a bit. Now the title orientates the short clip with a little bit of direction and focus, it seems to be about simply the arrival of this particular orange, its intensity and appearing is perhaps more important than what it is, suggesting a certain sort of abstract relation to the thing, and the film. Perhaps it’s more poem than story?

Take that brief shot of a cup, saucer and spoon and if you placed it in relation to other shots, then things change dramatically. Surround it with other cups and I have a work, that at a minimum, I might take to be about cups. Or surround it with other things ‘appearing’ as brief intensities of colour, and I’m perhaps got a film that is thinking about colour (perhaps in the spirit of the Delauney’s.

Relations between therefore carry great force to change what we understand the shot to be about.

This week’s theme begins to consider what sorts of relations there might be between other things, and how these might be filmed. These tasks invite poetic interpretation and an effort to think from something else’s point of view.

- make a six to ten second clip that is about someone else, not from your immediate family – and film them in a way that describes who you think they are, without filming their face

- make a six to ten second clip that describes an object from the point of view of an animal in your home

- make a six to ten second clip that describes either air, sky, water, or earth, from the point of view of a plant

- in each clip you should only show the parts of things, not wholes

Technical

- each clip should be six to ten seconds in length (if you use Vine they will be six)

- editing can be done in camera, or after

- the video needs to be published into your blog (you can use vimeo, blip.tv, or embed them yourselves)

- there should be one video clip per blog post

- the source media needs to be available as H.264 video

Film Essay

Apologies for any confusion as I’ve just looked at various documents and things are confusing. The film essay that is due shortly, the outline is located here, the actual description via a Google document, and you can submit it via a google form.

K-Films

Axel writes about Almost Architecture, a substantial K-Film about signage and the city (Matt Soar has a research interest as a designer in signage and collects the old building signs of Montréal), noting the importance of use of the soundscape. Sound, in my experience, is one of the things that is often overlooked but makes an enormous difference. Prani looks at Bear 71, a high end interactive documentary that does an intriguing mix of data, location, and ecology. Imogen meanwhile explores two interactive documentaries that aren’t made in Korsakow, seeing what sorts of things are done, being done, and what they’re about and how. Henry watches two student works and is impressed, one is an abstract consideration of collage and time, the other uses a simple, repeatable premise to make an intimate observational work. Natalie has some good comments and observations about another student film -these are great models of what you need to do for the short essay. Axel wonders about themes and consistency in some of the works viewed (good questions), and the importance of the interfaces designed and used.

Your Commentary on K-Films

James likes Born to Die, a student film from 2012. I haven’t invited you to look at previous work like this before, and I’m not sure if it will make any difference to anything, but in general I’m surprised by the generally positive response to previous work. Confusion is a recurring comment, but this, of itself, is neither a good or bad thing. Kate looks at Ennui and uses de Bono’s hats to do the work.

Intermedia Art, Lost Leaders, and Korsakow: An Interview with Matt Soar | media archaeology lab

This is an interview with Matt Soar about a current Korsakow film he’s working on, as well as Korsakow more broadly. Well worth reading to thicken up how we can understand what Korsakow does, is for, and how.

Intermedia Art, Lost Leaders, and Korsakow: An Interview with Matt Soar | media archaeology lab.

Lives, Stories, Narrative, Teleology

You can narrate your own life, but you do that after the fact, not during it. Just as I can narrate a football game after the fact and now infer an narrative arc, and even intentionality. However, while living my life, and even while playing the game, I am not narrating. This difference is important (in relation to understanding what narrative is, and is also the foundation of ethics) because one is always happening now and the other, even with our grammatical tricks of using the present tense, is always was. It is easy (and trivial) to infer causation afterwards, even where the causation is wrong, and causation is the heart of narrative.

The second problem arises because it makes my life the centre of how I want to think about narrative, and then there seems a small step to thinking that narrative equals the world, and if it can’t be narrated then it either can’t be understood, or doesn’t matter. This could be as simple an issue as using ‘me’ as the measuring instrument for the discussion (my life is a narrative). We can narrate anything we like about the world, but this is not the same thing as what the world is. This is similar to my point that I can narrate the ‘story’ of the match, but this is not the same thing as what the match is. To make it blunt: I can narrate sex, but I think you’re an idiot if you think that is the same thing as experiencing sex or what sex is (or love, hate, anger, joy, hunger, being drunk, coffee, blue, the sky the other night, a lover’s touch) – though it would our lives much less complicated.

In a story everything happens for a reason. Everything. The reason is to progress the story to its resolution, to what we call ‘closure’. Realist stories (and the definition of realism) is to make this highly artificial model appear natural, so that it relies on coincidence and character and various ways of representing itself (e.g. hiding the fact that it is a made up thing) so that things appear ‘like’ life. But unless you think you live in the Truman Show, our lives bear virtually no relation to stories in this sense, every day they are full of real accidents, coincidences, and, well, life. For instance, in a story, you only get sick for a reason (they’re bad, it’s a moral reflection, the story wants to consider mortality), in the real world we get sick because of ‘reasons’ but these reasons are germs, bugs, malevolent cells, etc, not because I want to consider mortality – just as many ‘bad’ people get cancer in the real world and die as ‘good’ people, it’s an unusual story that does that.

Symposium 2, the Anthologised Editing

Yeah, let’s begin with a whinge. Tuesday, teaching and meetings from 10:30 to 5:15. Wednesday, only time to teach, today should be my research day (a day spent writing, editing, reading) but instead am catching up here, doing admin. Tomorrow, meetings and additional teaching from 11:00 to 4:30 when I have to head home. So I jump in to my RSS feed for integrated to find 435 unread blog posts. (wipes brow.)

So, some catch up.

Bec notes around taxonomies that rather than work from a definition, make what you want to make and let someone else worry about what it is – or isn’t. Documentary is also about having something to say, and saying it. Mardy has very good notes, and yes, define things by what they can do, not what they mean. Gina notes that taxonomies are useful, but perhaps don’t misjudge this for what things are (something I’d certainly agree with). Torika picks up the point that taxonomies make the world seem discrete but in reality there is always and for ever variation between things, so what comes to be in one box rather than another is both arbitrary, and therefore informed by (pick: politics, power, ideology, etc). Ali notes the role of power in classification, and uses this to also think about Habermas, YouTube, Sørenssen, the public sphere and taxonomies. Sam adroitly notes the point that taxonomies are about trying to define and classify a world that, in actuality, is not the same thing as how we define and taxonomise it. Brenton sees that taxonomies create boundaries, which can cause stereotypes, whereas we might want to begin from the premise that everything is different in itself, not similar. Not sure Brenton realises how radical a proposition that is, but it is at the heart of recent work in what we call the ‘post humanities’. Laura has some notes, worth checking, ditto Koston… Tiana seems to have picked up the point about entanglement, also provides a good thing of what was described as the ‘linguistic error’ or ‘semiotic error’ where we think language is all there is and exhausts all that can be or is. We are trained to jump straight past the thing in itself (experience, reaction, object, event) to what it means, to its description or analysis. But what things do, and what we can do, is not the same thing as what they mean, or might mean (what that mosquito means for me is quite different to what I ‘mean’ for it, let alone what it means for my blood).

Symposium 04 Questions

- Bordwell and Thompson state that after watching Rail Road Turnbridge a person “cannot see bridges in the same way” thus experimental films are not just art for arts sake. Can/are Korsakow projects art for arts sake, or can they effect the way people see things? Or like Rail Road Turnbridge are they both at once?

- Bordwell and Thompson devote a lot of attention to the formal structure and sequence order to deconstruct films, yet through some i-Docs the individual creates their own unique structure. What other methods can we employ to deconstruct i-Docs, and does this interactive structure take some creative control away from the author/filmmaker?

- Do the readings of experimental films rely on the audience that is observing them? And if so to what extent is experimental film an interpretation?

- Can you present a persuasive argument using rhetorical form with a Korsakow type film?

Implied, Intended, Real, and Narrative

Correction and Update: Thomas Hatchman asked the tenacious questions, link corrected below!

Good questions and tenacity in today’s symposium from, I think Tom (and apologies if I’ve got the name wrong). I think the conversation was the idea that all is narrative, versus my contention that all is not narrative. To try to simplify, we can narrativise anything (there was a moon who fell in love with a star, the star did not feel the same way, so the moon became sad) but that is not the same thing as saying that everything is narrative (the moon ‘looks’ sad to us due to the sun’s reflection in concert with its craters). Our lives are a case in point. Stories are cause and effect narratives that, significantly, are teleological. This means they are ‘end directed’ or defined. Things happen for purposes in a story – if a train is late in a story it is because this will let two characters meet, an accident be avoided (or not avoided) and so on. It isn’t just late. If my train is late on the way home tonight, then alas it is just late. There isn’t some final cause in relation to me which is the reason why the train is late.

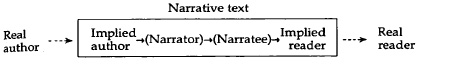

Also briefly touched on intentionality. This is also mentioned by the next reading by Ryan, but this drawing from Seymour Chatman might also help:

(Chatman, Seymour. Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1988. p. 151.Print.)

A narrative/story always has an author, as an intended statement/thing there is a real author (maker/creator) as well as an implied author within the work, while the narrator is a narrator present in the text. If they are not present there is still a sense and existing narrative voice that is a product of the text (which is why they are not the same as the real author).

Reading 04

The last readings (Bordwell and Thompson) was about narrative, documentary, non narrative and experimental film. The things we want to think about for Korsakow, and our Korsakow films, fall closer to non narrative and the experimental. One way to think about what then to “narrate” (in scare marks as it isn’t really narrative) and as a method to compose such works in Korsakow is through the idea of the list. So, this week’s readings, which I confess are on the academic scale at the upper end, begin from Ryan’s outline of narrative and story, where we can see that diaries and the like might not, for her, fit the definition. This definition, which is independent of any particular media (unlike Bordwell and Thompsons), also emphasises the role that the reader has, where the reader’s attribution of ‘intent’ (so understanding what ‘intent’ is is important) is the clincher.

From Ryan there is an extract from the computer game and platform studies scholar Ian Bogost. He is a materialist media scholar, who argues that to understand software, media, and so on it is not enough to pay attention to meaning but also to what the things are, and what they can do. A method he proposes to begin to do this is ‘ontography’, and in the extract he discusses how lists are not narrative, and what they might do. Listing, in some form, turns out to be a very practical way to approach making, and reading, Korsakow films.

Finally there is a supplementary reading from material media archeologist Wolfgang Ernst. This is heavy going (well, he is German), and like Bogost, Ernst argues that simply studying media from the point of view of what they mean (whether sociopolitically, as texts, or for audiences doesn’t much matter) very much misses what they are.

[Extract] Ryan, Marie-Laure. Avatars of Story. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006. (PDF)

[Extract] Bogost, Ian. Alien Phenomenology, or What It’s Like to Be a Thing. Minneapolis: University Press of Minnesota, 2012. Print. (PDF)

Supplementary Reading (mega advanced)

[Extract] Ernst, Wolfgang. Digital Memory and the Archive (Electronic Mediations). Ed. Jussi Parikka. Univ Of Minnesota Press, 2012. Print. (PDF)

Constraint 04

Relations. Literal ones this time. Things gain meaning for us because we place them in relation with each other, via us. When we do this what the thing is in itself becomes almost secondary to the ‘force’ of the relation. For example that bench out my window is a seat which has a particular relation to my body. When I sit on it I am aware that it is timber, made from a log, but it’s ‘woodenness’ or ‘timberness’ is not really what matters to me about the bench so much as its ‘benchness’. What it is in itself (wood, grain, cellulose, once a tree trunk, something living, food for termites and other insects) is reduced because it is placed and so understood in relations by and via me (my bench, a rustic bench, furniture, garden decoration).

The tasks this week invite you to think about yourself in regards to relations. What relations form you?

- make a six to ten second clip that is about your immediate family (your immediate relations) – however, you cannot show anyone’s face

- make a six to ten second clip that shows objects or things that you have that define you

- make a six to ten second clip that shows a parts of a place or places that define you

- in each clip you should only show the parts of things, not wholes

Technical

- each clip should be six to ten seconds in length (if you use Vine they will be six)

- editing can be done in camera, or after

- the video needs to be published into your blog (you can use vimeo, blip.tv, or embed them yourselves)

- there should be one video clip per blog post

- the source media needs to be available as H.264 video

Brief Videographic Moments (A Shot Is One Idea)

One thing the teaching staff will discuss in the coming week is whether we’ve noticed any changes in how things are being filmed. In my own class there was quite a difference between week two and week one, with the material much better.

When you’re filming like this, where you have at best 10 seconds, a good way to approach what you’re doing is to think of it as about one key idea, or about one thing. This doesn’t mean it might not have several shots, or move, but if it is about that object then make it about that object. If it is about light then don’t also make it about camera movement – unless the camera movement is how you make it about light. To use that last example. I might track/pan across a light, moving from dark, to burning light, to dark. Here the movement is used to make the clip address the idea of light in some way. However, if I film the light, and then move closer, then back a bit, then twirl around it a bit, the risk is that the movement gets in the way of what the shot is about, and comes across as indecision or insecurity – that you’re not comfortable with 6 or 10 seconds of just that light. Relax about the busyness, think of one shot as one idea, what you want that idea to be, and do it. Repeat if it doesn’t work.

Sørenssen, Sobchack, (Bought to you by the letter S)

Sam, writing about the Sørenssen essay, wonders about the democratisation of democracy, and the key question of whether all our access to making and distributing has realised Astruc’s vision. It’s a good question, and the idea that if you can use data to work out what people want then provide it, while one option, is also a risk to create sameness, homogeneity and repetition.

Zoe writes about the Sobchack essay and how QuickTime movies are likened to Cornell boxes. I also think this (Cornell boxes) is a very useful way to think about many Korsakow films, and as Zoe notes, perhaps your own computer is a sort of Cornell box too? Gina loves Astruc because it is about film making in itself. I agree. It isn’t about film making in the service of some master (action, narrative, audience, money) but trying to find a way to think it for itself. Respect, as Ali G would say.

Edward uses Sørenssen to think about the relation of technology to cinema, speculating about possible futures. Imogen like others notes the three main points of changes to making and access, more egalitarianism in media, and possible new forms. And his example of this is the elderly man on YouTube (which is a very interesting case study from the point of view of what video now is becoming). Laura also summarises the essay well, picking a very good quote: “there will be several cinemas”, that’s a nice way to think of this subject, it’s one variety of these several cinemas that we’re trying to invent. Koston has a nice overview of the rise of the digital camera and its impact on making, in terms of access but also that we can now see it (how easily we have forgotten what once was).

Bec has excellent dot point summary of the Sørenssen, wondering if the rise of amateur making is such a good thing. Mia recognises that the essay is from 2008 so was written before the smart phone + mobile internet + (Instagram video, Vine, etc) exploded, and so thinks about using a mobile phone to make documentaries. Astruc I would have expected to have been all over this, as this is surely (along with GoPro’s and their ilk) a camera stylo? Kylie discusses Astruc and Sørenssen in terms of the changes wrought by technological shifts. Miguel looks at Sørenssen and concludes that ‘true filmmakers’ posses ‘true power’, perhaps, but what work is ‘true’ doing here? (It is key to the argument but not actually defined.)

Nadya, taking some advice, wants to know if democratisation of media making also means the loss of film form, of I think she means informed, crafted, reflexive, self aware media making. It’s a great question.