This year’s university graduates will be graduating into a workplace which is significantly different from previous years, as Australians turn towards the emerging realm of the sharing economy.

The sharing economy is fuelled by collaborative consumption, meaning that consumers are moving away from traditional, centralised organisations and instead enlisting the services, skills and information shared by peer-to-peer communities. It is founded on the notion of access, rather than ownership.

Instead of booking hotel rooms, millions of people are now choosing Airbnb to fulfil their accommodation needs, which allows homeowners to rent out spare rooms in their apartment or house at their chosen rate. Similarly, taxi companies are facing serious threats from business models such as Uber and Lyft which connect passengers with drivers in a ride-sharing service.

Uber has arrived at a time when the Australian taxi industry is fundamentally flawed and is in desperate need of reform. Their innovative business model has seized a gap in the market and is now offering a more efficient, safe, and accountable experience.

The NSW Government has placed sanctions against the use of Uber, and other governments across Australia are currently debating its legality. Now is the time to assess how our consumption habits are changing with the arrival of the sharing economy, and adapt into these trends so that we can fully reap their innovative benefits.

Last year Time Magazine named collaborative consumption to be high on their list of 10 ideas that will change the world.

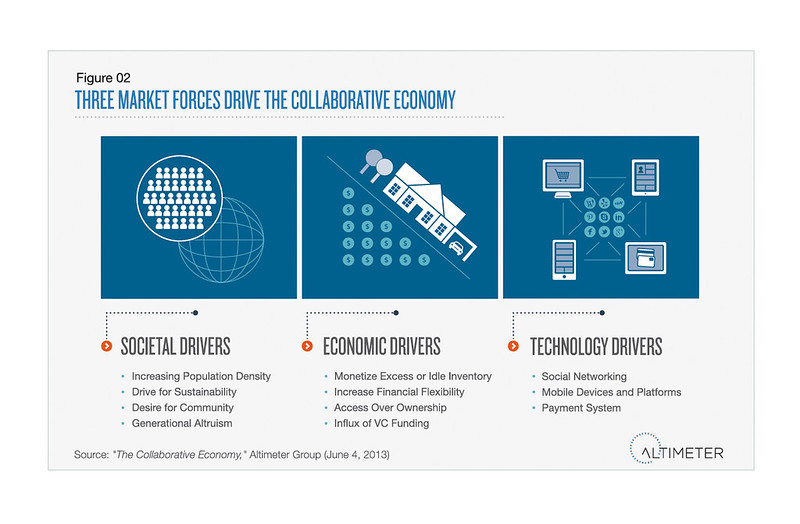

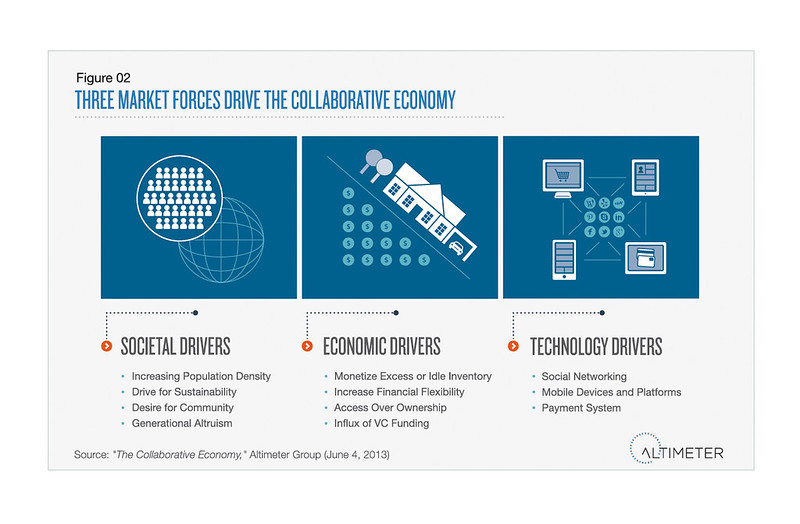

The sharing economy is driven by a very deep social and economic shift that has been enabled by developing technologies. Businesses in the sharing economy have found a way of matching ‘I need’s with ‘I have’s.

Open marketplaces such as Airtasker, Freelancer or oDesk allow users to outsource their skills to the highest bidder. This enables a more flexible use of talent, and is part of the growing casualisation of work which is fundamentally reshaping our conception of work and the employment market.

This is a reaction to the growing need to stay competitive in the globalised international marketplace. Skills are now being shared across national borders and jurisdictions to go wherever the money and demand is. What has resulted is a virtual global village, or a global market square, where skills and service are traded, bartered, and shared, extrapolating a model that is hundreds of years old.

Some organisations such as Google, Facebook, and more locally, NAB, are already using this trend to their benefit. By utilising strategically designed work spaces and the technique of ‘hotdesking’ they allow more interaction and collaboration between colleagues.

Melbourne City Council has also encouraged the use of shared resources with the Melbourne bike-share scheme, community rooftop garden projects, and carpooling schemes for city commuters. Collaboration on this scale can reduce waste, contribute to more community building, and invest in local economies.

The sharing economy is empowering because we are no longer passive consumers. We now have a changed role to play in the economic makeup of our societies. We are creators, collaborators, contributors, financiers, producers and providers.

The sharing economy is fuelled by reputation. The currency with which peers trade is trust. Modern consumers are placing their confidence in peer-reviews and recommendations, much more than advertisements or direct communication from a company. We seek the advice from users with similar backgrounds and experience, rather than trying to cut through the spin of corporations.

However, more organisations must continue to shift how they conduct themselves amidst the modern marketplace, by readjusting their understanding of the patterns of work. No longer are there strict working times, as the lines between personal and professional continually blur.

We need to readjust our expectations, as this cohort of graduates may be an army of digital-natives who are both flexi-workers and micro-entrepreneurs. This is an incredibly empowering time, however it does not come without criticisms.

Opponents of this trend warn that further generations will face worsened conditions and less job security. Many organisations resist the advent of new technologies for fear of change. However, major industry players believe that the collaborative revolution will be as big as the Industrial Revolution.

There are challenges that need to be overcome, such as existing legal structures which do not offer space for the emerging roles of the sharing economy. Copyright and intellectual property laws will continue presenting difficulties in instances of co-creation. The contractual rights and obligations of a flexible worker must be strengthened. But traditional models are outdated, and do not allow for the innovation and connectivity provided by our networked, multimedia age.

We are encountering a crucial paradigm shift in how we live, work, play, create, learn and consume. The employment market must prepare for modern graduates to live and breathe the characteristics of the sharing economy.