I love Melbourne’s Laneway Culture. Really, I do. And no, you most likely won’t find me with an obscure-coloured Holga and my Oxfords traipsing along these little lanes taking photographs of macarons in velvet-coloured boxes or sipping authentic chocolat chaud. I live too far away for this kind of endeavour, but when I do get the chance, oh do I try.

But I’m here to engage with Professor Martyn Hook’s articulation of the reason behind the sudden emergence of such culture. And it has nothing to do with the quirkiness of them hipsters.

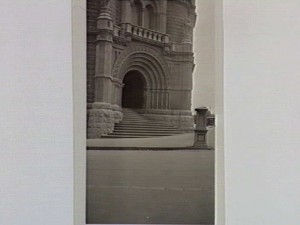

Night Vision of Melbourne, Australia

Melbourne seen from the International Space Station at night reveals its young history. Unlike the winding streets in older European cities, Melbourne’s streetlights follow a more planned grid system. Established in 1835 around the natural bay of Port Phillip, Melbourne is the capital of the state of Victoria in Australia.

I’d like you take a deep breath in before we continue. Don’t you just want to say “Whoa” but with a full stop instead of a violent exclamation point? I’m spellbound by the composition, the singularity, all perpendicular lines, unbent, untwisted. And if you zoom in a lot closer, you’ll see what I’m talking about with those laneways.

Professor Martyn of RMIT’s architecture and design described the superimposing of the grid not as a landscape function, but in fact, an economic one. The Laneway Culture is vibrant and unconventionally appealing, and that’s exactly the point. The very city of Melbourne, divided up by streets thanks to the power of the grid lines, is an invitation for commerce. What can be done there? What can be traded? How can these smaller streets be used?

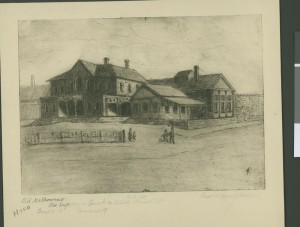

And RMIT University works the same way. Looking back, RMIT had been a closed-off University, barricaded by a watchman who made certain that only students were allowed to pass through, specifically in Bowen Street. Nowadays, anyone can pretty much walk in, walk through and no one would give a water’s dam that they are actually walking through an academic institution. And why would they?

RMIT organises itself as close to how the city organises itself too. The University invites the city in so there’s the commerce there. And RMIT is surrounded by civic centres, much like the whole of Melbourne. Looking from Bowen Street, there’s the State Library of Victoria to your right and across from that, Melbourne Central. Up top is the Old Melbourne Gaol, and to your left, the City Baths. Sound civitas enough for you?

Practice

I loved the notion of “letting the city in.” It makes me think of the security issues that may arise with this pursuit of commerce; the value of the University as a whole in the eyes of both students and staff as opposed to those unaffiliated to it. The Laneway Culture (more of in the next post) and the superimposing of a grid on every new map back whence Colonial days because systems are a must.

It really does make me think more of the reasons behind the making of the city, and specifically, of RMIT itself and how I may be able to document Building 20’s significance in my future project.

Some in the list:

- Economic Function

- Commerce

- Surrounded by civic centres – what does this mean?

- Maybe Building 20’s exterior placement has some sort of significance that can be researched and further developed?

- Does the interior of Building 20 have anything to do with its surroundings? And if so, how can I use this to my advantage in telling my story and representing place?

Oh, lots to think about!