Pitch – THE CARETAKER

What happens when all that is left is the quietness? No pounding of gavels or black robes and unwashed wigs harassing the hallways? Of murderers on trial, of justice-seekers and curious peepers? No one really knows, but the old man who cleans, cleans, cleans.

IDEA

Title: The Caretaker

Format: Experimental Short Film – documentary, found-footage film, use of archived videos, recorded shots of Building 20 itself, use of sounds

Length: 5-6mins (approximately)

SYNOPSIS

This short film follows six acts or segments of the life of the caretaker, a poetic reverie of the court as a place and of him as an occupant of the place.

CHOSEN IDEA – Why?

I chose this idea for two reasons:

1. Character – the Caretaker

Why I chose this idea is galvanised by the photograph I took of the the signage just outside of the establishment: CARETAKER PRESS TO RING.

It immediately gave me the perception that someone else, apart from your usual magistrates and judges, jury, clerks and court-persons, was also present in the area albeit mostly overlooked and unknown. The caretaker is an unknown character, but he is vital for the running of this great bastion of law. I felt that his life, who he is and what he does needs to be known and explored more.

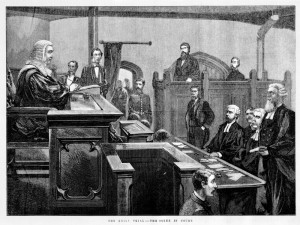

2. The Court – as a place

First time visiting the Court, I marvelled at its architectural grandeur, and on my second visit, the holy reverence the place has towards what it was before: A Magistrates’ Court. I’ve been to the Melbourne Magistrates’ Court in Williams Street, having done some work experience there beforehand and though it is a lot more architecturally-progressive and forward-looking, I could imagine the same hustle and bustle of activity happening in the Old Magistrates’ Court as well. This time, however, these sounds are now reduced to honourable silences, simple echoes of the past, punctuated mostly by natural, diegetic sounds.

The caretaker as a physical character of the court, and my own impression of what it feels like to be in that building is what made me chose to do this idea. Visually, I believe that finding appropriate stimuli to what I am trying to convey both using found-footage and own recordings, scavenged and edited, alongside the sounds of the place, will be both a challenge for me as a future filmmaker but also an opportunity to explore the nuances of what this great building used to stand for.

CONCEPT

The main concept of which my idea is inspired by is found in Shelley Hornstein’s “Losing Site: Architecture, Memory and Place.”

Quoting her, “Architecture exists as a physical entity and therefore registers as a place that we come to remember…and [architecture] can exist to be found beyond the physical site itself in our recollection of it.”

She states that the physical object itself, in a spatial framework is the “vehicle” that connects us to our memories of that place.

I work around this concept in two ways:

1. The architecture can exist or be found beyond the physical site itself in our recollection of it.

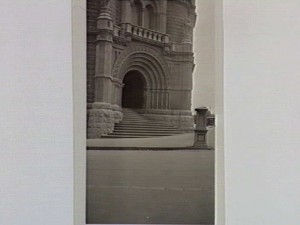

This is where the idea of scavenging found-footage works well. I’ve been to the physical site of Building 20. I’ve seen the architecture and framework, smelled the musty, carpeted air and heard the sounds associated to the building (muffled voices and violent footsteps on such an austere, quiet dominion). Therefore, the challenge now is finding works of the past, these found-footage that is associated with both the memory of the place, the physicality of the place itself, and the reverence to what the place stands for then, as the Old Magistrates Court, and of now.

2. We being capable of “orchestrating in tandem at least two parallel images of places.”

The character of the Caretaker comes into play here. I’ve read novels, watched movies and television shows and seen photographs wherein the setting of the Court is magnified and used. This is where the character of the Caretaker, what I imagined him to be based on what I’ve read plus my own experience traversing the corridors of the building, is being explored. What does he feel walking along those quiet hallways when everyone has left? What are his thoughts with the squeaking of the door hinges and the loud rapping of his feet on the floors?

This approach is explained by the following examples:

VISUAL/AUDIO REFERENCES

There are two main video references:

1. Alter Bahnhof Video Walk – Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller

Check it out here: http://www.cardiffmiller.com/artworks/walks/alterbahnhof_video.html

The participants watch things unfold on the small screen but feel the presence of those events deeply because of being situated in the exact location where the footage was shot. As they follow the moving images (and try to frame them as if they were the camera operator) a strange confusion of realities occurs. In this confusion, the past and present conflate and Cardiff and Miller guide us through a meditation on memory and reveal the poignant moments of being alive and present.

I was inspired by Cardiff and Miller’s exploration of both the past and the present in the video walk. This is one of the reasons why I chose to this particular medium as an inspiration. There’s a strange confusion of realities, and I plan to highlight this with using found-footage and real footage of the court itself.

2. The Illustrated Auschwitz

Check it out here: https://vimeo.com/100185502

“A small, cheap personal film, shot on super 8 . . . it is a documentary that completely avoids talking heads and the usual parade of facts and figures . . . the film poses the question, it is already implicitly there in the title, of how to illustrate such experience, of how to represent the unrepresentable.

Similarly, this documentary talks about the experience of a woman who survived the infamous Auschwitz concentration camp as a child. The film documents her story while providing a collage of images, most not directly linked to the story.

I will use footage to both directly link and not link it to the story I’m telling in, providing the abstract of emotion in the court.

One main sound reference:

3. Nocturne – 360documentaries

Check it out here: http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/360/nocturne/5617366

Mainly the beginning sounds, diegetic, introducing the setting. I’m going to be utilising the same entry in my piece before the visuals begin.

4. Other –

archive.org sounds and reels.

WORK SO FAR

1. Video –

I went to Building 20 with my trusty Everio HD Camcorder to film myself walking through the buildings and room in Building 20. I specifically chose to use this camera just so I can see what a “grainy” footage would look like.

For the final recording, I will be using the JVC Pro HD camera.

For editing, I will be using Adobe Premier Pro and thanks to George, special effects.

2. Footage – archive.org, sounds, photographs, etc.

I’ve started compiling some footage that I will be using in this folder.

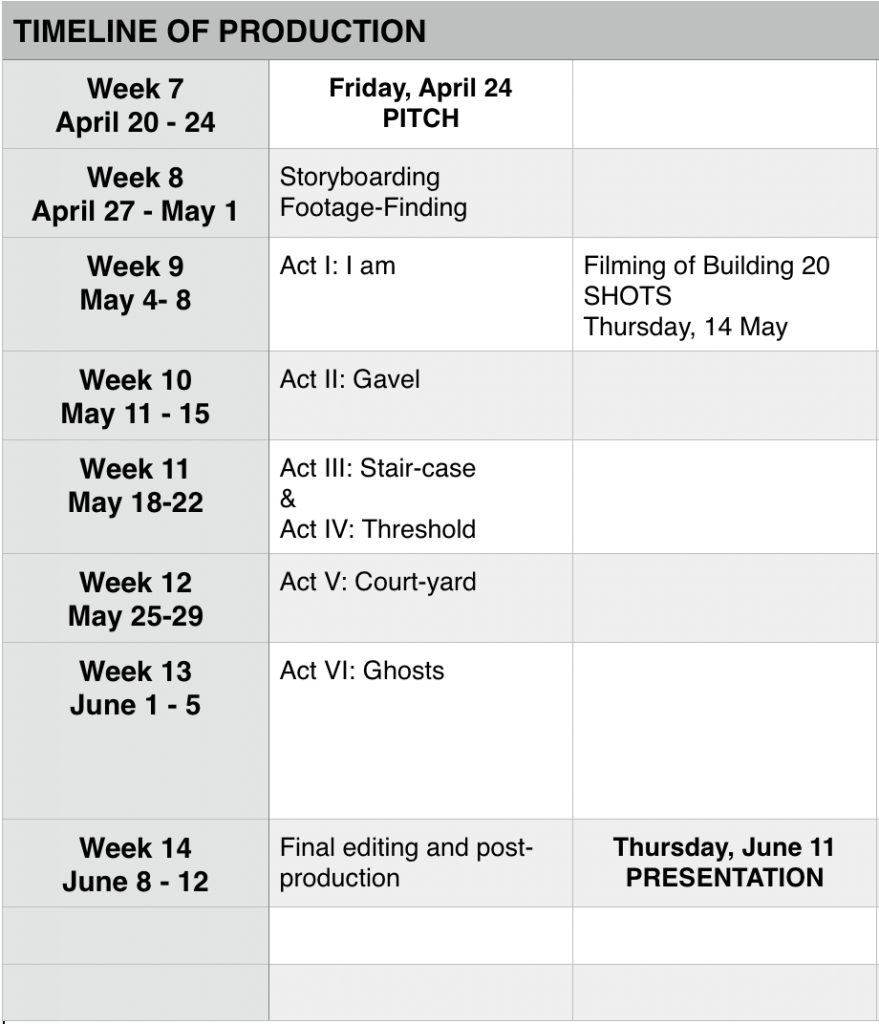

3. Six Acts:

I’ve also come up with the six acts or segments that my video is divided up in which helps in categorising and organising production:

Each Act explores a different aspect of the Place. i.e. Act I – I am introduces the character of the Caretaker, Act II- Gavel is about the utilising of the court and so forth.

Act Length:

30-40 seconds each, max 1 minute

ORDER OF WORK

ACCESS & HELP

Filming – may need to use tracking equipment for the tracking shots; people to help out on the day of the shoot

Adobe Premier Pro – general editing queries

WORKS TO DATE

Check out my Ghosts and Spaces page here for past and up-and-coming blog posts and constant updates about the film!

One look at the professor, entering an intimate class of 12 (and sometimes less) and you know that he’s got a bag-full of knowledge to share. And sharing he so articulately does.

One look at the professor, entering an intimate class of 12 (and sometimes less) and you know that he’s got a bag-full of knowledge to share. And sharing he so articulately does.