She Drives lives! Making this film has been a really valuable, rewarding experience and I’m really proud of how my group worked together to achieve what I think is a pretty high quality finished product. It’s the first short film I’ve made during my degree that I would be happy putting in a portfolio.

I’m especially pleased with how we navigated the creative process together. Collaboration is obviously an all-too-common sticking point for a lot of people, but for me it’s actually the best part of the filmmaking process because, most of the time, working to each other’s strengths results in a better product. I don’t have a digital SLR camera and couldn’t have achieved the kind of cinematography that Anna, Izzi and Zitni were able to achieve if I was on my own, so I was very happy they took on those roles… and She Drives looks incredible because of it. Likewise, I took on the challenge of bringing those shots to life through sound, and though I’m not 100% happy with the quality of the interview audio I am happy with how lived-in the film feels now that there’s a bed of atmospheric car noise deep in the mix.

(Note for the future, though: when shooting, SHUT UP ON SET. You never know what audio you’re going to end up needing, and a lot of our B-roll had people (especially me) talking and chatting all over it. I was able to piece together enough atmosphere from what we had plus some stock sounds, but it would have been much easier if I could have used the sound from our B-roll even just as a starting point.)

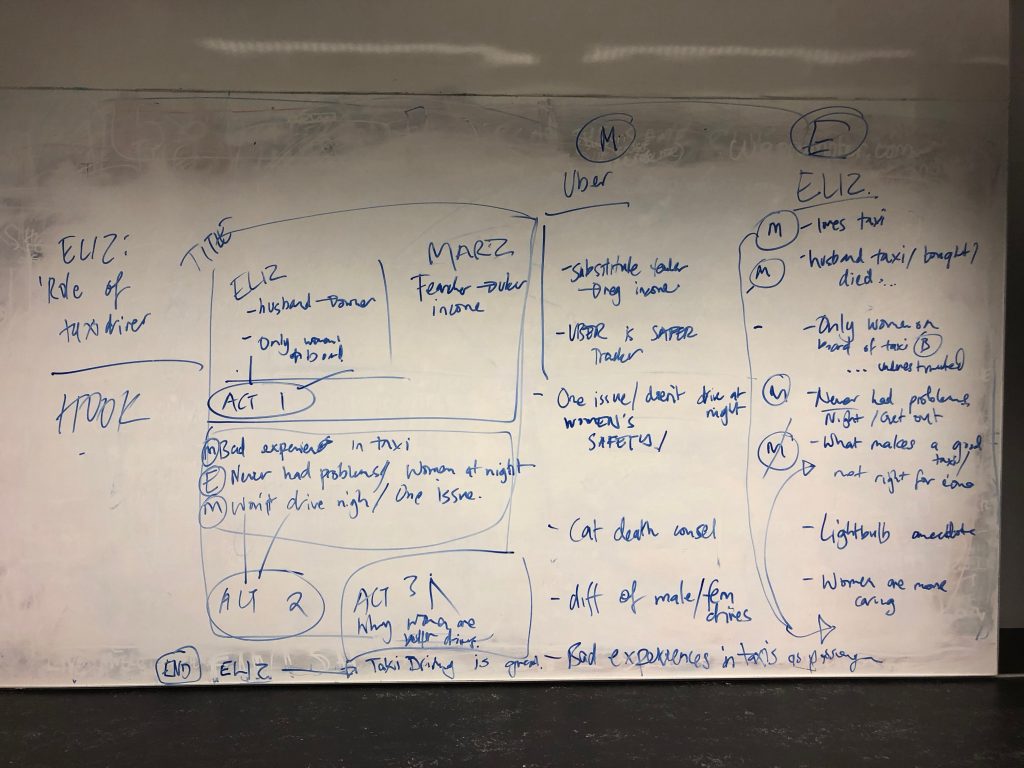

We did, as is always the case, face some challenges in getting She Drives finished. The most significant challenge was that we lost a lot of time waiting to set up an interview with a Shebah driver that ended up not happening. This was a major frustration because the Shebah driver was originally a core part of the idea we pitched, so without her we had to reconfigure our film into something different. It all ended up being fine, of course, and I’m happy with the film as it stands, but Izzi spent a lot of time going back-and-forth with Shebah when, in hindsight, that time was wasted and could have been better spent on something else. But even without saying anything, I think the group naturally understood that it’s better to move forward with the material you have (even if it’s not exactly what you first imagined) than to hold up production for an indeterminate amount of time while you try to get everything exactly as it was in your proposal. So we quickly moved on without a Shebah driver, and changed our film around to accommodate the loss. Through the whole production process, Izzi and Alice (who found our taxi driver, Elizabeth, and organised an interview with her) were both really great at keeping us all informed, and any lost time was really down to people outside of our group.

Other than losing our Shebah driver, we really didn’t have too many problems — or, I guess, any problems we did face were easily overcome, because we were quite harmonious as a group. We easily slipped into our roles, kept each other accountable, had no trouble asking each other to do things, and we all volunteered to help each other out when needed. I have to admit I was worried that a group of five might lead to some group-dynamic issues, but there were none at all.

Often, at least for me, these reflection exercises end up being a long list of problems large and small, with notes and ideas on how to avoid or deal with them in the future. It feels so refreshing that in my final studio, my reflection is full of nothing but positivity.