The Internet age has opened up a wealth of vast accessibility to a large range of media. Currently, we’re witnessing this change quite quickly and drastically. Just in my lifetime, I grew up obsessively recording material as it aired, pausing and recording through commercials, on many shelves worth of VHS tapes, from 1 of the big 3 channels we had— then rose digital television, offering over 20 free-to-air channels (the quality of content is questionable but hey, it’s better than just 5 channels to choose from). Then came DVD, and then short-lived HD-DVD booted out by Sony’s Blu-Ray. Now, we’re living in an age where physical copies aren’t the end-all-and-be-all of consuming entertainment with the inescapable rise of streamed on-demand content.

The rapid growth of online technology has changed the way markets are formed, especially in the film industry. In 2004, Chris Anderson penned a piece for Wired Magazine exploring the concept of ‘The Long Tail‘ and explored the new economic model the entertainment industry was latching onto. This concept covered the breadth of ‘hits and misses’ in entertainment and the opportunities for those ‘misses’ to gain their own steam as niche markets. I’d like to use this space to explore the changes technology has served for audiences as well as distributors as I prepare for contributing in this generation of constantly progressing media. What I’ve experienced as an avid audience member and consumer, and have seen as I research this topic, provides insight into opportunities film marketers can take on to innovate the methods being used.

Chris Anderson explains The Long Tail by way of an Arctic Monkeys album’s decline rate.

“We’re stuck in a hit-driven mindset — we think that if something isn’t a hit, it won’t make money and so it won’t return the cost of production” (Anderson, 2004). This hit driven mindset related to the 80/20 rule discussed in Albert-Làszló’ Barabàsi’s ‘Linked: The New Science of Networks‘ in 2002. “A power law distribution does not have a peak. Rather, a histogram following a power law is a continuously decreasing curve, implying that many small events coexist with a few large events.” (Barabàsi, 2002).

The ‘hit driven mindset’ refers to those with the power of exposure and popularity in the histogram, where all the blockbusters and general public hits reside. The ‘long tail’ end of the histogram where ‘many small events coexist’ is where the niche markets reside with possibly little exposure, but still residing with some profit nonetheless. The head of the histogram where the blockbusters reside used to be the one with all the power, leaving the niche markets in the tail unexposed, especially in the time before online dominance.

The age of the Internet has brought down the limitations of the physical world. Supply and demand —supply the material, and there will be a demand for that material— how strong that demand will be is not up for guesswork but the very fact that it’s available leaves it open to consumers. The endless ‘shelf space’ of online marketplaces which is further reinforced with the non-existent shelf life of the material, the endless opportunities for niche markets to gain steam are infinite, without the need for bulky overhead.

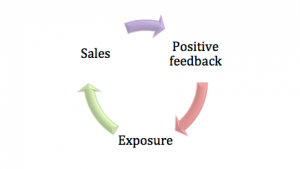

Anderson examines the rise of a book regarding British climbers touching death in the Andes, titled Touching The Void. Receiving critical acclaim that was not mirrored in its commercial success, Touching The Void fell from relevance. Ten years later, another book dealing with similar themes in climbing and tragedy titled Into Thin Air, storms into commercial success. Touching The Void suddenly becomes a best seller, spending 14 weeks on top of The New York Times Bestseller’s list, and spawned a docudrama in the thick of it. This would go on to prove the power of recommendation algorithms, as the success of Touching The Void can be pinpointed to Amazon.com’s recommendation algorithms, which then lead to the ‘positive feedback loop’

Up until recently, we as audiences and consumers have been subjected to mainstream blockbusters as a knee-jerk response to 20th century supply and demand trends, focusing on economic gain. This is not the case now.

Let’s take the rise of on-demand entertainment, which is quite often being heralded as the nail in the coffin for brick-and-mortar rental establishments. Video stores of course had their wide selection, but it was always constrained to availability and niche markets weren’t necessarily easily, and readily catered for. It’s not to be compared with what’s available to customers nowadays, where with a click of a mouse you’re led to a long list of similar films and television shows. An algorithm has replaced the video store clerk that suggests what your next rental should be, and with the wider selection online readily available, you might just find yourself watching something so obscure (yet familiar to your tastes) that you wouldn’t have found through non-technological means.

For example, we are seemingly in a world where our technologies are beginning to know us better than we know ourselves. Netflix’s algorithm’s are set up on intricate details of your watching habits ranging from what genre you often watch, down to the time of day you watch them. This information is then collated and what you watch next is determined and based off your habits that you might not necessarily even notice. On top of usage-generated algorithms and processes, Netflix possesses 76,897 genres. (Madrigal, 2014)

To build upon Netflix’s algorithms, Netflix’s engineering director Xavier Amatriain states that unlike eBay, their company model is based on recommendation rather than search, whereas eBay’s results is 90 percent search. Close to 80 percent of what people watch on Netflix stems from Netflix recommendations rather than search methods. (Vanderbilt, 2013)

Netflix, as well as Amazon’s recommendation examples shed light on a new way consumers can reach their next source of entertainment. This can greatly enhance the nature of film distribution. With the age we’re in now, filled with metadata and optimized search engines, the key to using this information is deconstructing the material. More specifically, tagging and precise marketing. Audiences and consumers alike have predilections that they’re accustomed and comfortable with and what The Long Tail’s analysis of Touching The Void presents is that consumers will consume when it’s closely related to their tastes.

This leads to the ancient proverb of ‘this film was marketed wrong’ (obviously not an ancient proverb, but something we’ve heard time and time again). We’ve seen critically acclaimed films fall under the bus when it comes to box office figures, though luckily, such films find themselves cult classics long after their theatrical run.

A film in which I’d like to draw attention to in this case is David Fincher’s 1999 (now) cult classic, Fight Club— a film displaying the degradation of society into consumerism and the crisis of masculinity into nihilism that stems from the very consumer-driven society it critiques. With a budget of $63M and a domestic United States return of $37M, (however, a worldwide return of $64M) the poor performance in the Unites States left 20th Century Fox sour. Art Linson, one of the producers of Fight Club recalls the initial screening to the Fox executives left them “flopping around like acid-crazed carp wondering how such a thing could even have happened.” (Linson, 2002)

Art Linson briefly describes his thought on the effects of Fight Club’s marketing on it’s release.

Linson believes that the film’s failure at the box office was due to poor marketing that was solely based on highlighting the fight scenes rather than the satirical black-comedy it is. Hell, the TV spots aired specifically during WWE (World Wrestling Entertainment) broadcasts. The marketing was detrimentally focused as the people meant to market this layered film misunderstood the morals the film actually held, creating a further disparity between the film and the general audience. Now, just recently at a panel at 2014’s San Diego Comic Con, David Fincher has revealed that it has since sold 13 million DVD copies ($156M), not including blu-ray, and not yet taking into account streamed online viewings.

At 24:48, the discussion on Fight Club’s next generation DVD success begins.

The way Fight Club and its promotion unfolded is looking to be a thing of the past. The long wait for films to find its niche audience and gain its deserved recognition is cut short by way of ‘the long tail’ of consumerism that we’re seeing. This opens up a plethora of opportunities for film distributors and filmmakers themselves, to be able to publicize the material truthfully without the need to embellish what executives would think to be ‘food for the masses’ is a great step towards progressing with the times. Knowing your audience is crucial, yet so is treating that audience with respect. Marketing a film like Fight Club as an action packed testosterone-fuelled boxing film, or advertising Jim Carrey’s dark turn in The Cable Guy as one of his Mask-esque or Ace Ventura-esque wacky film instead of a black comedy about alienation and desperation, sells the intended audience short and neglects to give the film the chance of gleaming first impressions.

This constantly expanding and broadening pool of markets means that so many more niche audiences exist, and the focus of targeting an audience is no longer pigeon-holed to a singular demographic of ‘mainstream’ entertainment goers. Now, the target market is virtually everyone and anyone, and with the advances of online technology, audiences are able to find their way around their tastes. The way this industry is moving along now is only an inkling of how it will progress in the near future. Audience participation is riding high and interactivity with films and the way they are found amongst audiences will only grow into a digitized relationship of what we once had with our local video store vendor. Fans and critics alike can share their critiques on the all-encompassing global network we all now reside in and this can only strengthen the future for not only the canonical marketing of films, but can also have a heavy hand in what can actually go into production, now that exposure is not only limited to the mainstream.

Anderson, Chris. Chris Anderson: The Long Tail Of The Music Industry. 2006. Web. 19 Feb. 2015.

Anderson, Chris. ‘Wired 12.10: The Long Tail‘. Archive.wired.com. N.p., 2004. Web. 18 Feb. 2015.

Barabási, Albert-László. Linked “The 80/20 Rule”. Cambridge, Mass.: Perseus Pub., 2002. Print.

Goldsmith, Jeff. Comic Con: “Fight Club” Panel. 2014. Audio Recording.

Linson, Art. Art Linson On David Fincher’s Fight Club. 2012. Web. 17 Feb. 2015.

Linson, Art. What Just Happened? “Fight Club”. New York: Bloomsbury, 2002. Print.

Madrigal, Alexis. ‘How Netflix Reverse Engineered Hollywood‘. The Atlantic. N.p., 2014. Web. 18 Feb. 2015.

The-numbers.com,. ‘Fight Club – Box Office Data, DVD And Blu-Ray Sales, Movie News, Cast And Crew Information – The Numbers‘. N.p., 2015. Web. 16 Feb. 2015.

Vanderbilt, Tom. ‘The Science Behind The Netflix Algorithms That Decide What You’ll Watch Next | WIRED‘. WIRED. N.p., 2013. Web. 20 Feb. 2015.