Month: April 2018

📞

FINDING PEOPLE – an adventure in multiple parts

My least favourite part of documentary making – organising people to be in it.

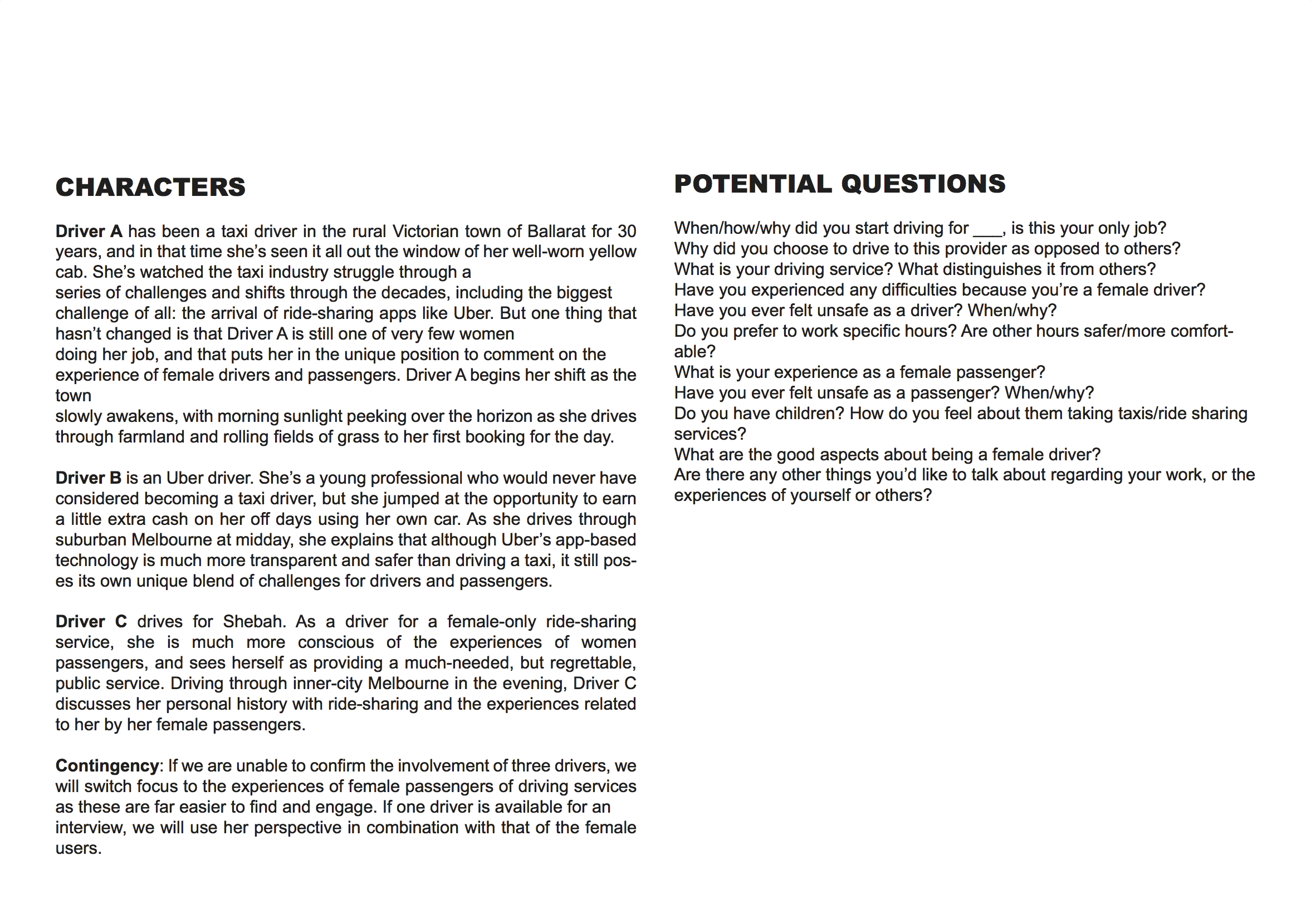

After settling upon interviewing one female taxi driver, one female Uber driver, and one Sheba driver, we are now into the phase of creating questions and contacting people.

PERSON 1: TAXI DRIVER

Rohan has given us the great idea of interviewing a taxi driver he met in Ballarat who is apparently quite the character, and who he believes to be the only female taxi driver in the town.

This should also provide a great visual contrast with the ‘city’ driver of the Uber, and the ‘suburban’ locating of the Shebah.

We intend to call the taxi rank, pretending to have driven with her previously in order to make contact and ask her to be in the film.

Update #1: There are in fact many female taxi drivers in Ballarat. We are going to be in further contact and see who wants to be involved in the film.

Update #2: Several of the women from the taxi rank are willing to be involved. We are calling Elizabeth who is in charge.

Update #3: She is very nice, and will be in the film.

PERSON 2: UBER DRIVER

This is the easy part, as Bradley has a friend who is an Uber driver.

Update #1: She is in fact a recently retired Uber driver. We think it will be fine to have her in the film regardless, so we are pursuing her for the film.

Update #2: Her name is Marz. Not entirely sure if she’s particularly excited to be in the film or if she would rather not. Bradley is in contact and I’ve said we can always do an audio only interview, or otherwise see if she knows another female driver who would be more willing to be involved.

Update #3: Marz is willing to be in the documentary, and as an old drama teacher is happy to be on camera, and comfortable here.

Update #4: Marz is unavailable until the 16th of May. We have locked in this date.

PERSON 3: SHEBAH

This will be the most difficult of the three to secure, as it is a relatively small company and none of us have previous connections. We are emailing the company to see if they have any women who would be interested in being in the film.

Update #1: We have been in touch with a very nice man at the company, and he is talking to a few women about being in the film.

Update #2: Nice man at Shebah has said there is a woman who is interested in being in the documentary. We have sent further information about the film, and possible shooting dates.

Update #3: Not sure how this was conveyed, but the woman thought it was a phone interview, and has thus pulled out. Nice man at Shebah is finding another woman to be in our film.

Update #4: Another woman has agreed to be in our film! Hooray! We have sent a comprehensive description of the film and our approach, as well as possible shoot dates.

Update #5: She also thought it was a phone interview somehow! And has since pulled out. Nice man at Shebah is finding us another person, although I’ve said we can make it work with a phone / audio only interview if required.

Update #6: No reply from Shebah. Deadline approaching. We have decided to can the Shebah and focus on building a solid dialogue between the two other women, and focussing on the gendered discussion of the industry, whilst building up the contrasts of old/young, county/city, and the respective aesthetic palettes that accompany them.

📷

This week’s film Grizzly Man is a film that I have seen multiple times. It’s a footage about a man using entirely ‘found footage’ – a documentary that despite being almost entirely shot by its subject, was created without its subject being truly present, as he was dead before Herzog began work on the film.

This got me thinking about films which do similar things. Documentaries which are composed entirely of found footage, or those whose stories are told via narration alone.

It reminded me of a film by my favourite documentarian Sean Dunne, who created a film called Cam Girlz, in which its subjects, with one exception, are never interviewed on camera. This is a very rare occurrence for a feature length film. It doesn’t use any found footage, and instead creates a colourful, insightful piece filled with beautiful cinematography.

The choice to interview the women of the film off camera was deliberate, and has resulted in wonderfully intimate conversations that sound truly genuine and afford a deeper look into these women’s lives than could have ever been achieved with the pressure of an on-camera interview.

See below for the trailer and a short interview with the filmmaker that further explains his choices and the outcomes of these cinematic decisions –

🇺🇸

I missed this week’s documentary, so thought I’d share my favourite documentary here.

It’s a rare practice for documentary films to make a film about a subject with a lot of established study behind it, and disregard this completely. This is the case for Oxyana, a film about the town of Oceana in America and the oxycontin abuse rife throughout the area. The film is a prime example of effective documentary filmmaking, in two ways. First, it is affecting for the viewer. Secondly, it is cathartic and important for the subjects.

Despite the tendency to include facts, figures, and statistics within documentary films, the audience cannot truly understand the meaning of such information. The statistics presented, though impressive, are inconceivable to the average viewer – that is, there is no way for them to really understand their impact.

Referring to a human issue with facts and figures alone is a dehumanising process. In order to change the dialogue surrounding a human issue, you must humanise it, and let the people effected speak for themselves.

This is exactly what Oxyana does.

OXYANA TRAILER from Sean Dunne on Vimeo.

Tucked in the Appalachian mountains of Southern West Virginia, Oceana, is a small, once thriving coal-mining town that has fallen victim to the fast spreading scourge of prescription painkiller Oxycontin. As the coal industry slowly declined and times got tough, a black market for the drug sprung up and along with it a rash of prostitution, theft and murder. Soon its own residents had nicknamed the town Oxyana and it began to live up to its reputation as abuse, addiction and overdoses became commonplace. Oxyana is a harrowing front line account of a community in the grips of an epidemic, told through the voices of the addicts, the dealers and all those affected. It is a haunting glimpse into an American nightmare unfolding before our eyes, a cautionary tale told with raw and unflinching honesty.

Winner of Best New Documentary Director, Tribeca Film Festival 2013

Special Jury Mention for Best Documentary, Tribeca Film Festival 2013

Devoid of any statistics, or even hard facts, the film is composed solely of interviews with the townspeople of Oxyana, many of whom are current users of oxycontin, who speak about the impact that the drug has had upon their lives and the people around them. They illuminate the ways that people are introduced to the drug, how it is so addictive, some even shooting up on screen. The viewer sees the impact it has has on these people, and the suffering it has caused them because they are brought face to face with those affected as they tell their own story. There is no narrator, no crew presence. In a way it is as though these people are speaking directly to you, sharing their story. In this way, real empathy comes in, as the viewer is allowed a true connection and understanding with the people on screen and the issue they are presented with.

This is the documentary filmmaking style which I believe to be the most effective in creating meaningful change.

Further to this, the film was an emotionally cathartic experience for the subjects. Many documentaries are made in the vein of ‘poverty porn’ or ‘documentary tourism’ wherein subjects’s stories are taken without intent to give back to the subjects or affect real change. Subjects are narrated over, devoid of true agency in their own stories. Oxyana was afforded such deep interaction and access to the townspeople of Oceana because of their unique approach in letting their subjects speak freely without the intention of imposing another dialogue over the top. Many filmmakers had tried to create the same documentary, however had been met with resistance, as their approach sought to inflict another narrative, showcase the people and town as nothing more than one a freak show of ‘dirty drug addicts.’ The approach that Oxyana took was to give the subjects agency over their own story, show them with empathy, and in this way, telling these stories became a very cathartic process for the subjects, and as more and more townspeople found out about this, more came forward actively seeking to participate in the film.

Documentaries should never solely be about the end product, about the film, the story. In order to be affecting, truthful, and empathetic, they must first and foremost be about the people.

Watch the full film online here:

💁

IDEAS FOR THE BIG DOC

This week we brought in our ideas for potential documentaries to pursue for the group project. For our project, I wanted to look at an issue, rather than simply doing another portrait of an individual.

We each presented a variety of ideas from documenting houses, to beekeepers, and eventually decided to go forward with my idea of looking at Sheba, a female-only ride service, interviewing female drivers, and looking at the gender dynamics and issues present in the industry.

This idea was initially formed through a discussion I had had with a friend about taking taxis and Ubers home at night, and how no women we knew felt entirely comfortable in this situation. This progressed into talking about the recently founded company Sheba, which is an all female ride sharing service, wherein no men are allowed as drivers or passengers. We talked about the environment that we live in that necessitates such services, and the way that, beyond simply making women feel safer, this service was also opening up opportunities for a whole range of people, including those with disabilities, and parents who need someone to pick their children up from school. The dialogue here is that women are more trustworthy, empathetic, and reliable in this role.

Catching a Shebah means sitting in the front seat of the car without feeling vulnerable, no longer feeling limited by the time of day, knowing that your little one is in safe hands when you can’t drop them off and so much more. Our passengers are ecstatic that they no longer have to dread the end of the night and figuring out how to get home safe. We drive women and primary school-aged children, and boys up to 18 can ride with us if accompanied by a female guardian.

For drivers, Shebah means working when it suits them, feeling safe about who they pick up and experiencing financial freedom – our drivers keep 85% of their fares.

This idea transformed into interviewing one woman from a taxi service, one woman from Uber, and one from Sheba, and looking at their experiences, why they chose to drive with that particular service, and fostering a conversation about the gender dynamics of today, articulated through the particular dynamic of driver/passenger.

💃

The Trouble with Merle – QUESTION OF THE DAY

Does the documentarian have an obligation to step in and make clear that they don’t approve of the marks expressed? Does this change if the documentarian has a prominent role of personal narration in the film?