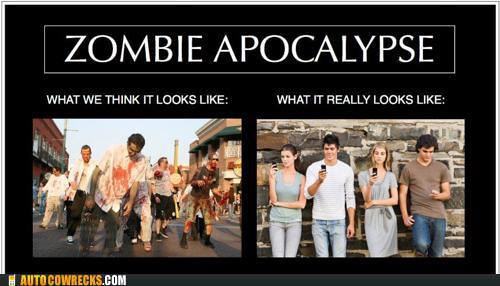

W11: Zombie Apocalypse

via Flickr http://flic.kr/p/gszBb2

via Flickr http://flic.kr/p/gszBb2

via Flickr http://flic.kr/p/g7eBuS

via Flickr http://flic.kr/p/g6AQh8

via Flickr http://flic.kr/p/fUeP6t

I’m with Lucy – I <3 socks

via Flickr http://flic.kr/p/fCKEd2

via Flickr http://flic.kr/p/fCKCHe

The extract from George Landow’s “Hypertext 3.0: Critical Theory and New Media in an Era of Globalization” pinpoints some important ideas about how stories and narratives are structured within new media forms.

He argues that “hypertext challenges narrative and all literary form based on linearity, [and] calls into question ideas of plot and story current since Aristotle.” For the most part, I feel that we think of this in terms of electronic forms of print, or making what was traditionally print media an interactive and interwoven experience. In this, we experience different kinds of media from different sources.

But I also think that this can be used to explain the ways in which we consume other media, particularly television.

It can be seen more and more that people want an interactive experience from television viewing. Michael Wesch explains how TV was traditionally a one-way medium, whereby people would congregate around a TV and watch a program at a time and in a way that is dictated by the televisions networks.

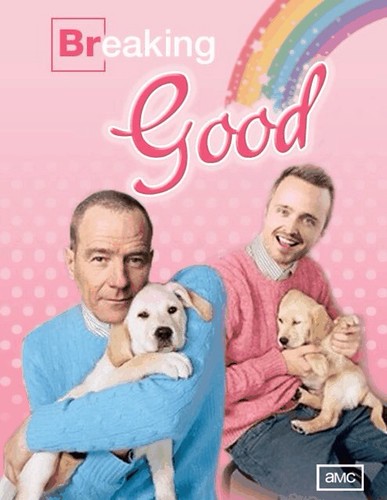

However, now people are viewing TV according to their own schedules, on any number of devices, on demand, out of order and so on. As such, it’s interesting to see media creators writing for these trends and technologies that support it.

Case in point: Arrested Development season 4. This show was originally broadcast like any other show, with up to 24 episodes in a season. It was critically acclaimed and had a cult following but was cancelled after 3 seasons. But in May 2013 it made its return on Netflix, the online subscriber viewing platform. Not only was it unique in being produced exclusively for Netflix, but its format was completely re-orchestrated to include 15 new episodes that could be watched in any particular order.

In this, the author “grants readers more power” to read the narrative in the order they wish. Whilst ultimately the narrative as a whole will be the same, the experience changes according to the order in which you view the episodes.

Although this alone may not explicitly relate to hypertext, it does lend to some of the ideas about why authors use hypertext, and particulary why it is so relevant to reading and viewing trends of today.

Furthermore, Landow’s point that authors use hypertext to create combinatorial fiction is relevant to almost any television program with a widespread following.

Although we no longer gather around a TV set to experience a show together as one imagined community, many people share in discussions online through social media and web forums. It is in these virtual spaces that many authors provide hypertext materials, things that add to the original and basic text.

For example, behind the scenes footage, interviews with actors and so on. These texts are available to viewers such that they have the power to extrapolate from the story worlds provided in the original text. They may explore additional areas of interest in ways that may not be immediately available through the primary text, but knowingly and readily available.

These examples embody Landow’s key characteristics of what hypertext includes:

Out of the three videos I viewed as part of this week’s online/virtual unlecture, Michael Wesch’s “From Knowledgeable to Knowledge-able” was the most poignant for me.

His points on how students of today use technology, approach their education and how this works within the institution of higher education are paramount to the ideas we cover in Networked Media, and how I want to be thinking about my education in general.

Being able to find, sort, analyse, criticise and create new information is something I think all students either think they will/have/can learn at university. However, I think many of us are misguided in how we go about this. I don’t think it’s just about learning how to research particular issues or topics of interest, and how we work through a process of finding some sort of ‘solution’ within them. But rather, our learning and higher education experiences should be about making meaning – by way of addressing real issues, utilising the human resources we have at university (other students, tutors, lecturers etc) and harnessing our informational resources.

I think he really gets it right in pinning together those three things. As Adrian said outright from the start of this Networked Media course, we have all the informational resources we need, we are able to connect with like-minded people across the globe, and we can seek out real issues. But within a higher education environment we’re able to practice how we utilise old and new media, harness old and new ways of sourcing information and collaborate.

Because it is a matter of practice. Creating meaning and being able to solve problems is a practice that takes training and some guidance.

As Sir Ken Robinson highlights in his Ted Talk “Do Schools Kill Creativity?”, education should be embracing the unique ways that students evidently absorb information and learn.

In the case of networking and utilising technologies, most of the information young people and students consume and share is via electronic, interactive networking platforms. So why do we still adhere to one-directional, outdated ways of learning such as essay writing or reading printed academic writings? It’s clear that these aren’t favourable or necessarily effective for students in the 21st century.

George Landow’s article “Hypertext 3.0: Critical Theory and New Media in an Era of Globalization” gives some interesting insights on how we read and analyse hypertext.

For me, a big part of practicing online networking and blogging is understanding the ways in which your work can benefit from the network itself. Your writing and ideas can be instantaneously linked with others. Landow’s description of the first kind of hypertext prose pinpointed how I had used networking and blogging sites in the past: placing links without hypertext into an HTML template that includes navigation links.

By utilising the features of hypertext more extensively (e.g. linking to other sites and content), we not only include draw on the benefits of this information, but instantaneously insert ourselves and our work into a larger context.

This is at once an exciting and terrifying thing for a student – many of us guard our work from peers and ‘the big wide world’ in fear of it not looking up to scratch. So I agree with Landow that it makes for excellent academic practice to introduce and utilise hypertext as a way of pushing students and writers in general towards connecting with like-minded creators/thinkers.

Furthermore, I like the idea of hypertext as reflecting non-linear reading practice. The way in which modern audiences consume/read texts in hardly ever linear, and certainly carries some ‘hyper’ characteristics. I hardly know a single person of my own ago who will sit and watch TV without checking their phone throughout the program, or work at a computer without multiple screen and windows open to constantly switch between.

Jay David Bolter also hits the nail on the head in the first sentence of his article “Writing Space: The Computer, Hypertext, and the History of Writing”: “writing is a technology for collective memory, for preserving and passing on human experience”. Hypertext quintessentially directs readers between different forms of information in order to shape a particular experience. It draws upon multiple sources and directs the reader towards a particular experience and understanding.

Hypertext reflects and influences modern reading/viewing practices, so it makes sense that it should be integrated into our learning and writing process.