via Flickr http://flic.kr/p/g7eBuS

Media / TV / RMIT / Digi-what?

via Flickr http://flic.kr/p/g7eBuS

This week’s unsymposium focused closely on the idea of constrained vs. unlimited networks, and scale-free networks.

Elliot touched on Barabasi and the comparisons between unlimited vs. unlimited networks in answering our question “does the network have a centre? Or do we create centres for our own networks?”. Jasmine agreed in saying that “the network” doesn’t necessarily have a centre, but there are more heavily weighted nodes. For example there are some sites we visit more than others.

Brian sort of extrapolated from this to emphasise networks as being dynamic – growing and evolving all the time. This linked into Adrian’s reminder that in the Networked Media course we are looking at scale-free networks like the internet which do not have constraints. They’re limitless and are always growing and shifting, unfixed by ultimate powers (nodes).

Adrian went into the idea of ‘heritage’ media e.g. newspapers, TV, which are centralised media – they stem from TV towers, printing presses etc whereas the internet doesn’t come from any such centralised source. There is no main server – there are ‘hubs’, and if any of these fail, the others will route around the failed one to overcome its failure. It’s designed to avoid such problems inherent to centralised media networks. Ahh, the glories of the internet…

This fed into some ideas we were considering in class today, relating to the Galloway reading, that despite the ideological idea that the internet is this wonderfully open, free, non-hierarchical network, it’s users do not support the democratic affordances of the web as a network as most of us still flock to the same search engines, link to the same websites that we feel are most popular and notable, and connect via the same platforms. That’s a bit of a generalisation, but I feel it’s a warranted one, and Jasmine sort of touched on this in the lecture today as well. Through this, the network of the web then serves to give power to the big players of the internet e.g. Google, Facebook which become very powerful as informational hubs.

The good news here is that it isn’t concrete and the network isn’t necessarily monopolised by these key players/powers. As Brian said, the network is always growing and evolving, and so the power still shifts around somewhat. I think ultimately, the common idea that the internet is a democratised platform for its users is flawed in that there are still powers at play and ‘consumers’ of the internet serve as nodes which feed into other, more heavily connected nodes such that they become more powerful.

Adrian also mentioned that all you need is something like 3 heavily weighted hubs in a network and it becomes 6 degrees of separation. Wonder if he’s ever played The Wiki Game?

This week’s reading was on Manovich’s “Database as Symbolic Form”.

He suggests that we have moved away from old media objects such as the novel, the cinema etc. which have some sort of romanticism tied to it and are the quintessential expression of a cultural narrative. The new age, modern equivalent: the database. Manovich argues that we undoubtedly want to “develop the poetics, aesthetics and ethics of this database” such that it isn’t just a cold, culture-less proliferation of texts, images and other data that are void of structure.

I think it’s interesting how as a society of people we feel compelled to do this in order to determine and appoint a cultural value to something. It’s not enough for it to exist in an unstructured way, things have to have solid meaning and cultural value.

It sort of links back to what Adrian was saying the lecture in Week 7, about how publishing as an industry will not die. It will become governemnt-subsidised like all other industries that have some kind of cultural value yet are seemingly less commercially viable e.g. the theatre, opera. At the time I though well sure, that’s true for things like books and theatre and opera which have a romantic sort of past. But then in class (that same day if I’m right), we took a look at CowBird. This site was particularly unique in that it preserved the open web format for sharing stories and doesn’t have an app (shock! horror!). The site claims that Apps are destined for obsolescence and will be the CD-ROMs of tomorrow.

But why? Why does one form of new technology (CD-ROMs being relatively new) cultivate less cultural importance than others? Why are open web formats more culturally important or romantic than apps and CD-ROMs. And why do we feel we need to arrange databases in an attempt to adorn it with such meaning?

I’ve been thinking about it over the last couple of weeks and I can’t think of an answer just yet. It may be one of those “only time will tell matters” or I may need to sharpen my ‘speculative think’ tools :/

via Flickr http://flic.kr/p/g6AQh8

Lots of talk about video games this week. I love talk about video games, pretty much for the same reason I love talk about graphic design: because I know nothing about it, so it fascinates me!

Elliot said that Hypertext tends to provide different kinds of links but video games present a partiucalr diegesis that you move through intrinsically. He thinks that overall, he wouldn’t consider video games hypertext. Jasmine disagreed, as she though they can be as the interface of the games changes according to the user’s choices, which makes it a different experience.

I think both claims are fair, I’d lean more towards Elliot’s point as I see that there is a particular diegesis that has been designed for the user to be taken one way or another, but then again I agree with Jasmine’s point that there is a difference of experience.

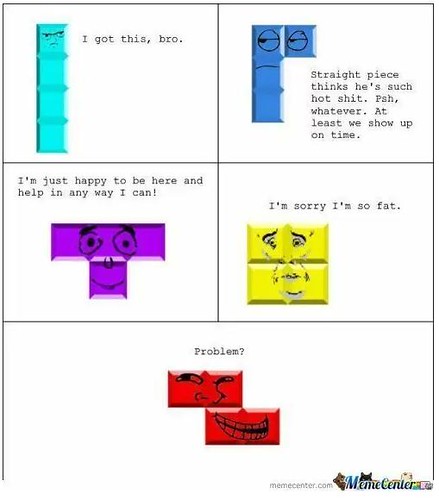

Adrian think that games don’t necessarily have narrative e.g. Tetris. I see what he means, but I still think that with things like that there’s still some sort of story. Even in a game of Tetris there is tension, climax, conflict, triumph, the user is always the protagonist with a partiuclar goal in mind and that goddamn I-shaped block that appears when you’re just about to hit the roof and have nowhere to put it is the VILLAIN! I think elements of narrative exist – it just simplifies them through blocks and simple objectives.

Adrian pointed out that words that serve as signifiers of consecutiveness and seriality are obsolete in hypertext e.g. hence, therefore. This is due to each node being highly granular and can be arrived at at time and read in an isolated way. Important to consider when trying to write a hypertext narrative – I think as student’s it’s been hammered into our brains to be able to write in cohesive, serial manners, so this part of writing a hypertext narrative could be a challenging but refreshing one.

The 80/20 rule – the only other time I’d really considered this was one time when I read some article where Miranda Kerr described her diet as being 80 percent good foods, 20 percent treats. So I guess it’s safe to say Barabasi’s ideas of an 80/20 rule are a bit of a step up from that.

Linking the 80/20 rule and the power law together, I think it’s very true that in many cases, extraordinary powerful or big events are a result of or relative to smaller ones. I think it’s particularly true in an industrialised world that there are more things that are ordinary, which prop up the extraordinary.

If we think of a different ratio – the 99/1 – the occupy movement is an exact demonstration of this, and, in fact, is a protest against the reality that out of the working efforts made by 99 percent of the world’s people, 1 percent of the global population reaps the financial rewards.

But back to the idea of participation and power law in networked media, this site has a helpful explanation and diagram of the Power Laws of Participation.

via Flickr http://flic.kr/p/fUeP6t

I felt like last week’s symposium was full of controversial claims about reality and authorial intent.

Elliot stated that documentaries make statements about reality, and hypertext presents alternatives to this reality. Adrian said that Wikipedia isn’t documentary but it is non-fiction – an interactive collaborative work of non-fiction. He also raised the point of how we look at Wikipedia as not being 100% reliable yet it’s the first point of call for when we want to know something… Perhaps in this highly technological age of easily accessible information convenience sometimes triumphs over quality of information.

Then came this idea about whether or not you can gauge an author’s intent through a piece of their work, or if they could really influence the way their work is read. Was this an attempt to discredit literary theory? I disagree with Adrian’s point that a work speaks for itself, and you have no access to an author. Sure, we don’t ‘have access’ to their thoughts directly, but there’s always an intention and any kind of work has been produced with that in mind. Of course, readings of that work change over time and in different context, but this just refreshes the relevance of the work, which could perhaps be their intention all along.

I’d lean a little more towards Elliot in what he said about causality and structure in the rhyming trick that Adrian used – these things are created to influence our responses. They’re not 100% definite, but they’re likely to prompt a particular result. Which I suppose is after all just design…

I walked away from this ‘unlecture’ thinking ‘well if you can guarantee intent, and authorship is such a flimsy notion, then why do we create? Why distribute work or present our thoughts in this way? Is it just to fulfill the need of others to find meaning for themselves, or is it a (arguably failed) attempt at expressing our own ideas?’

Haven’t figured out the answer yet!

I’m with Lucy – I <3 socks

Some key things I took away from the W6 ‘Unlecture’:

Hypertext in terms of storytelling in different media…

Elliot: YouTube annotations kind of tried to do it, but it hasn’t taken off. Korakow is a more successful example of this.

Jasmine: still have to watch things from start to end in order to read the whole story. When you take away elements of linearity, you experience the narrative in a different way.

Brian: The 2012 London Olympic Opening Ceremony was an example of hypertexts that have become second nature – it’s one story and about one thing (linear) but still jumps around from music and cultural aspects.

Adrian: Multiple points are always available to the viewer in the hypertext experience. It’s about structural and formal relations between parts but not navigation. There are affordances of comp and system – experiences you want to ‘author’, and experiences desired by the viewer.

My favourite take-away idea from this ‘unlecture’ was that despite this idea people have of being ‘authors’ or ‘experience designers’, you can never guarantee intent – but hypertext willingly embraces this and uses it to an advantage.