Jenny Weight, in her paper ‘At the edge of documentary: participatory online nonfiction’, asks some important questions about the role of the filmmaker in recent and immerging forms of participatory documentary permeating the current online space. The growth and dependence of the user in user generated content or UGC, and how this might affect the role of the author or filmmaker.

“What happens to the media maker’s voice when he or she is dependent on other people’s media? Can arguments be mounted and sustained in sophisticated ways if you are reliant on UGC? What is to be gained from UGC, and what lost?” (Weight, J 2013)

Over the course of the semester, considering what is or isn’t participatory, I define participatory documentary as a work in which the user or subjects co-author/create the content. They can co- create the content in many ways; by saying what they want featured or included in the documentary, by existing uncensored, unchanged or un-manipulated by the filmmaker, they exist as they are and the filmmaker creates the story around them rather than the subject fitting into the idea of the filmmaker. They can also exist to direct the story in ways the filmmaker couldn’t preconceive. Ross McElwee is a good example of a kind of participatory documentary where the filmmaker adopts a strong rhetoric and point of view despite the high level of unscripted and uncensored participation from his Subjects. Sherman’s March and Time Indefinite, McElwee’s voice comes out strongly through his use of post-production techniques where his narrative overlay is structured to weave together the footage he has accumulated, (often over years). He could have never known how the story would turn out, nor did he have a clear idea of where he was going. It was the level of participation by the subjects which determined the course the filmmaker took. In response to Weight’s question “What is to be gained from” the user or in this case, the participant? Perhaps more than the filmmaker could have imagined upon use of his own recourses.

The ability to allow the subject to evolve and exist, is a quality I look for in film. It is my belief that if a filmmaker can capture the true essence of a person, place or thing and not only allow them to be, but translate that essence through film – they have done their job. If the filmmaker can get out of the way, and use their skills and technique to tell the story of the person (rather than tell the filmmaker’s “idea” of that person), then it will be a successful pilgrimage.

For the context of this short reflection, I will limit the exploration of what can be considered participatory documentary because the range is broad regarding the medium, platform and subjects involved. What influenced my personal project, was actually the circumstances around this particular studio. I was also careful not to preconceive a story or idea as time and recourses were limited. We were encouraged to begin our search in a broad way, focusing on community groups or more than one person. From the outset, the focus was – what can we do for the participant? How can we benefit this person or group of people in some way?

How can we represent the person in a way which helps them? In Bill Nichols’ ‘Why are Ethical Issues Central to Documentary Filmmaking?’ he says “documentaries also stand for or represent the interests of others”, he goes on to say that (documentary filmmakers), “speak for the interests of others”. What an unbelievable responsibility! This project was an opportunity for me to find

someone and see what happened when I allowed as much room for them to participate as possible. It was a relief to not have to create a story, but to find a subject and/or idea that interested me, and investigate it using first the essay film form and then the short documentary form. I could find a subject/person/place and create a space where I could film them offering as much information about themselves or situation as possible.

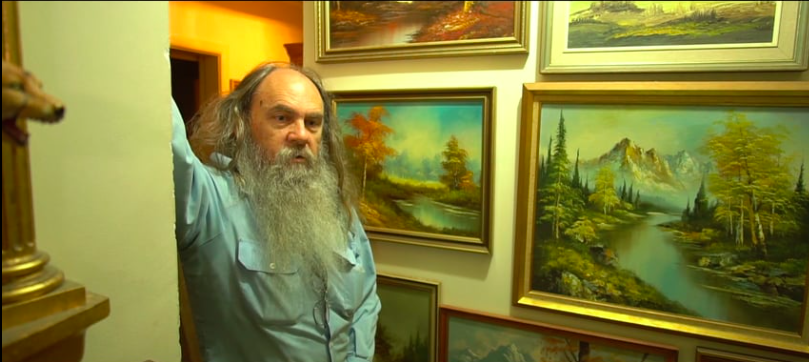

Originally I set out to document the Camberwell Markets; the old timers and collectors who had been buying and selling there for over 20 years. I realized quickly that the physical act of collecting wasn’t that interesting for an average audience member. They were more interested, in the test screening, in the individual person. In particular, they liked Leigh – an eccentric but charismatic hoarder with a bone to pick and a beard 2 feet long. The audience response was, “we’d like to see more of him”. During our conversations at the Markets, Leigh had mentioned that he would be happy to have me at his home to show me more of his ‘hoarding’. So I knew that there was opportunity and practicality to going in that direction. I had access, a willing participant, and an engaging subject matter. I also believed that I wouldn’t need to construct too much content. I could allow Leigh to be himself and structure the shoot and shooting style accordingly to suit him. I knew what he wanted too. To be the star of the show, to come across in a quirky, interesting way and at the same time showing off some of his dearest items. He also liked to talk and I knew that he would want to be represented in an interesting way.

The implementation of a participatory approach wasn’t too difficult in my case because I had a subject who was willing to show off and play in front of a camera. What I had to do was structure the shoot in a way where I could enable him to express himself, but also add a physical element and create some action. Rather than him talking throughout, we recorded him doing daily tasks like taking the bins in, making a coffee, strolling in his garden – moments that weren’t directed to camera. The subject of the film, Leigh, is quite obviously a hoarder, but I didn’t want to go into deep and serious interviews about dark or shameful feelings. This is one of the beautiful elements about participatory documentary is that I perceive or expect someone to have shame around their hoarding like any addiction. But there is another element I wouldn’t have written in to my story. Leigh had a lot of excitement and pride about some of his objects. There were definite moments of temporary and fleeting self-consciousness, but there were funny moments and he had a genuine childlike excitement to “show off” his toys. These little moments, often can’t be planned or predetermined in this context. The filmmaker needs to get to know the subject and allow them to be in order to let them live in front of a camera. Whatever you need to do to make your subject feel comfortable is a key. I knew that Leigh liked talking, but I also knew that he would get board of that (which he did), and so I had other activities planned for him which allowed him to be physical and get out of self. When a subject is in “doing” or being physically active, they are less likely to think about themselves or how they look. This can be the death of any film! The self- conscious subject.

From the Camberwell market interviews, I knew that Leigh would reveal gems about himself and his habits naturally as he spoke, told stories and showed us around his home. I knew this because he had demonstrated this at the markets. I asked him only a few questions and he took over the conversation, taking it where he wanted and talking about whatever came up for him. It made me feel less perverse as well. It’s more interesting when things can be revealed about a person without directly talking about it, simply by the way they talk about unrelated things, how they keep their homes, how they dress. The home environment is private, personal and extremely

revealing. When Leigh invited me to his home, I knew that we would have more than enough footage for a 4 to 5-minute short documentary.

The essay film was a good experiment in expressing a unique point of view about a subject. With specific focus on how something was cut together, narrated, composed – all let to an experimental portrait of personal perspective. My essay film focused on what brought people to the markets and the experience I have when I go there and interact with the locals. From the essay to the next Project Brief, I decided that it was far more interesting focusing on the life of another person and the potential that could bring to a story rather than what I could write on my own. The more I thought and discovered about the person, the more engaged I became in the process. The less I tried to construct a narrative and the more I tried to accommodate Leigh’s personality, the more enjoyable this particular filming process was. It was the perfect opportunity to practice participation without extreme manipulation. Of course there is going to be change and construction in post-production. I transcribed all my footage and rearranged it quite dramatically in order to create a flow, but ultimately, his words weren’t taken out of context to mean something other than what he intended. What Leigh was projecting about himself was not reorganized or intentionally misinterpreted. It was arranged to create a more engaging structure and cohesion which the audience could follow.

Leighs and I haven’t seen each other since the shoot. I need to visit him face to face because he doesn’t own a computer or smart phone which means in order for him to review the work, I need to take it to him and make sure that he’s happy with it before I make it public. Leigh was happy for me to film him because he had been filmed before by ABC and other filmmakers. He wasn’t new to the process which made it easier for me not knowing what the outcome would be. An important consideration for me is managing people’s expectations especially the participant, under promising and then hopefully, over delivering. There are a lot of people who would agree to be filmed without being offered anything, but we feel like we need to offer them something and tell them how good it’s going to be when we might not need too. I made sure Leigh knew that this was for a student production, I wasn’t sure what the outcome would be, as long as he was happy coming along for the ride and I would respect him and his decision to make it public (or not), in the process.

Personally, the participation has allowed me to experience making something more for the purpose of serving someone else. I would never have thought to make a documentary about a hoarder and had I not been encouraged to be open minded about the Market goers, the participants I started with there, the feedback session – all, in a sense, different levels of participation, I would never have ended up with Leigh.

A genuine intention by the filmmaker to engage with the subject/s in a participatory way, to allow them to bring something to the work, following it through with an open mind, can lead to places we never would have thought of on our own power. It allows room for inspiration and new information if we are open and receptive. It has been a wonderful way of working, I have really enjoyed this studio.

References

- 1) Weight, J 2013, ‘At the Edge of Documentary’, TEXT Special ISSUE 18: Nonfiction Now, RMIT UNIVERSITY

- 2) Nichols, B 2001, Introduction to Documentary, Indiana University Press

- 3) Ross McElwee, Sherman’s March, (1986)

- 4) Ross McElwee, Time Indefinite, (1993)