by Samuel Kininmonth

Everyday in Australia thousands of people are communicating with each other by reproducing and sharing content online, illegally. Many instances of this new type of communication, enabled by digital mediums, do not fall under any copyright exemptions, which form part of Australia’s current copyright regime (Illic, 2015). Copyright exemptions differentiate intellectual property from other kinds of property with their caveats for allowing unauthorized reproduction of works in public interest. They are integral to copyright’s moral framing, limiting reproduction only enough to encourage the creation of new works. Australia’s system of copyright exceptions exists as ‘fair dealing’ under the 1968 Copyright Act (Cth). Fair dealing uses a system of categories with specific attributes to denote whether a work should be classified under fair dealing. This has the drawback of falling behind the public need as the slow machinations of law struggle to keep up with accelerating technological advances in communication. In order to facilitate greater policy flexibility, Australia is considering adopting the American system of Fair use. Fair use weighs a potentially infringing work against a set of measures but does not proscribe exact kinds of works, making it more future proof. However, as demonstrated in Cariou v Prince, the fair use system’s flexibility might also be detrimental for content creators. Copyright requires a constant balancing act between public and private interests. This essay will examine whether the changing way people share culture requires a change of the current fair dealing regime in Australia.

Copyright is a system fundamentally designed to allow the commodification of culture in the age of mechanical reproduction; yet it has always harboured a utilitarian underside. The Statute of Anne is normally attributed as the origin of modern copyright law. English printers who had previously self administered a form of copyright (which they retained, not the authors) were undercut by their ‘unauthorised’ Scottish counterparts and lobbied the reigning monarch, Queen Anne, to, in their words, ‘protect the interests of authors’ (Lessig, 2004). What started as a commercial process took on a host of other moral facets. It became not just a method of extracting value from intellectual property (IP) but also a way of keeping the works true to their authors’ intentions. Through this moral frame authors expected attribution and sought to stop ‘debasement’ of their works. It is here that copyright branches from other legal property systems. While in many ways IP is property like any other; you can buy it, sell it, rent it, lease it etc. It has moral caveats for both the individual and the public. Only IP specifically allows reproduction of a work for comment or criticism, for education or satire. This is because it is the ownership of communication; the privatisation of part of what could form the public discourse. Reproducing a text in order to criticize or satirise is inherent to the copyright system. The system requires these contingencies to allow people and organisations to communicate, for society to grow; for the public good. These contingencies are different internationally; in the US they are called ‘fair use’ in Australia ‘Fair Dealing’. As digital mediums become the norm for communication, fair use and fair dealing will rise in prominence. Copyright’s commercial nature has always been paramount to its proponents but the provisions to use IP as a communication tool have been present in some form too. In Australia this takes the form of ‘fair dealing’.

Fair dealing existed before the Copyright Act (1968) in Australia and the debate surrounding IP has not been confined to this one period. The law is always playing catch up to the latest media society has adopted. Under the 1911 Imperial Copyright Act prior to the 1968 Copyright Act, television and sound broadcasts did not fall under copyright and newsreel copyright treated the content as a series of still images as opposed to a continuous whole (Bowne, 2015). The 1968 Act updated the law to protect a host of works and extended the term of copyright in Australia from 50 years after the death of the author to 70 years (1911 Copyright Act, 1968 Copyright Act). Extended too, were the fair dealing exceptions which now allowed parody and satire. Fair dealing now covered Research and study (section 40 Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), review and criticism (s41), parody and Satire (with some exceptions) (s41A), “reporting the news” (s42), legal advice (although the federal Crown is deemed to own copyright in federal statutes, and the Crown in each State in state statutes)(s43). Fair dealing refers to the public’s need to reproduce a copyrighted work in order to engage with it in the public sphere. These exceptions do have certain moral caveats such as the requirement for sufficient acknowledgement of the original work and the exclusion of works that are held to debase the original work. Copyright continued to change later too with the addition of computer software and games in 1984 (Bowne, 2015). While The 1968 Copyright Act was important in Australia’s copyright history, introducing parody and satire to fair dealing, there were developments preceding and following it too.

While the average Australian might have viewed the copyright developments of the 20th century as distant and arcane, digital media has thrown the debate into the forefront of the public imagination. The mass adoption of the internet has created an appetite for immediate, cheap and convenient access to the wealth of human knowledge and art. Consumers have never been truly passive but digital mediums have allowed people to showcase the way people interact using popular culture that is distinct from mere consumption (Suzor and Hunter, 2015). This digital way of interacting with popular culture comes into contention with copyright law and highlights a growing commodification of culture. Illic (2015) notes that online message boards that reproduce content in order to communicate new social meanings are not protected under Australia’s current fair dealing regime. Current online methods of communicating such as ‘memes’ (A picture with a caption often used in a subversive way that relies on mass adoption to create a ‘trope’ like effect) require a re-imagining in the way copyrighted content is used. Online storytelling via pictures is the language of the internet (Illic, 2015). It represents part of what Labato and Thomas (2015) term ‘the informal media economy’, an unregulated space that comprises a large part of the world’s communication. To formalize and control these informal activities might result in what Suzor and Hunter (2015) term a celestial jukebox, where every use requires payment, as opposed to a publicly available library of Alexandria that the Internet was promised to be. “Fair dealing criminalizes digital culture and discriminates against two generations of young people” (Illic, 2015, p.173). Under fair dealing pastiche or homage are not held to be adequate defences. Content must attempt to rebrand itself as satire, which is covered by fair dealing. Bowne (2015) suggests the addition of the defence of homage to the fair dealing criteria, while Illic (2015) suggests adopting the entirely new system of ‘fair use’ like the United States. The public awareness of copyright law and reform in the digital era has led many to call for the adoption of systems used internationally in countries such as the US.

An Australian Law Reform Commission report (2013) recommended that Australia replace fair dealing with the US style fair use approach to copyright exceptions. ‘Copyright and the Digital Economy’ (ALRC, 2013, p.16) stated that ‘fair use would be less flexible and less suited to the digital age than the open ended fair use exception’. This reflects the quickly transforming nature of digital content use and the inability of fair dealing to stay properly relevant. Fair use exceptions are different to fair dealing by using the term ‘such as’ in the legislation, suggesting, but not limiting fair use to similar categories found in fair dealing (U.S. Copyright Office, 2015). The U.S. Copyright Act proscribes four factors as a test of whether a work should be held to be fair use. The first factor is the purpose or character of the use; whether or not the use is intended for commercial or non-profit means. The nature of the copyrighted work also has bearing; factual works tend to have more latitude for copying for public good. The third factor refers to the amount or substantiality of the work taken in relation to the work as a whole e.g. taking a page from a book or short story reflect different amounts of appropriation. The final factor to be taken into consideration is the effect of the new work on the market for the original. A derivative work that is competing directly with the original work is unlikely to benefit from fair use. Fair use results in a greater freedom for users, it is more open ended and can be adapted to future technology more easily (Herman, 2015). Australia is considering adopting fair use to replace fair dealing in order to ‘future proof’ legislation but there is consternation about how that flexibility might affect content owners.

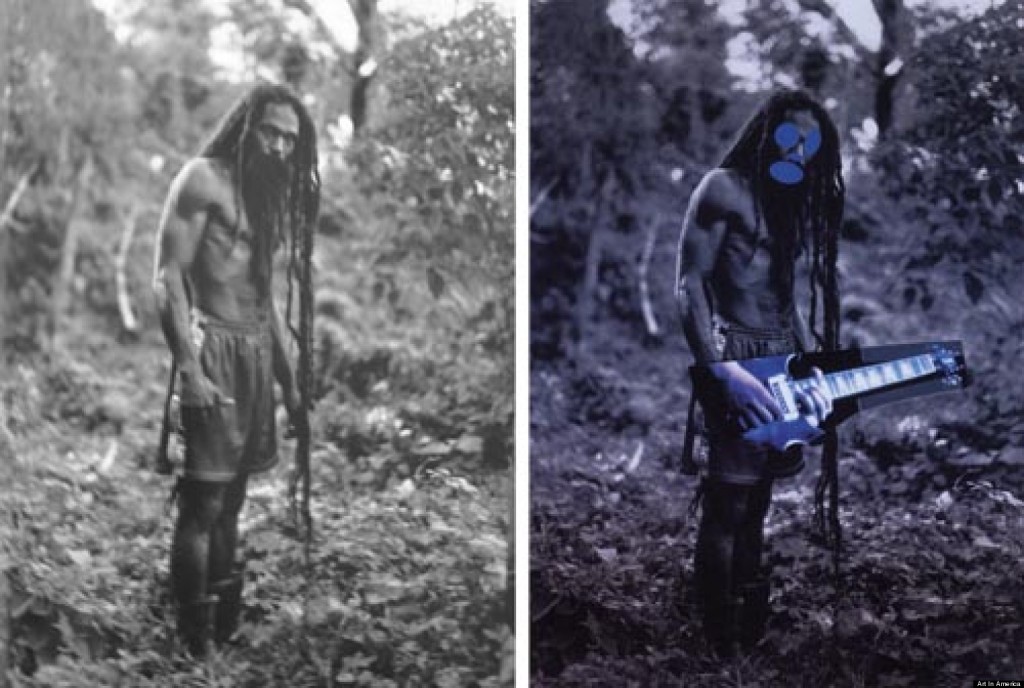

Left: Cariou’s original photo. Right: Prince’s adaption.

An illustration of fair uses potential boundaries can be found in the recent case of Cariou v. Prince. Cariou is a French photographer who spent several years in Jamaica photographing Rastafarian people. He published his photos in a book called ‘Yes Rasta’, which sold few copies (Azran, 2014). Richard Prince is a highly successful ‘appropriation artist’ who, having bought Yes Rasta while on holidays, proceeded to use the photographs in it as raw material in his art (Allan, 2013). Prince held an exhibition of the works called ‘Canalzone’ and made a substantial amount of money from the sale of some of the works (Allan, 2013). Cariou discovered this exhibition and sued Prince for copyright infringement. The defence asserted that Prince’s use of the works was ‘transformative’ and protected under the US fair use exemptions. The court found in favour of Cariou; the works used substantial amounts of the photos, sometimes the entire photo was printed with only minor additions. Further, Prince did not suggest any overt message with the works, which ruled out the defence of satire (Herman, 2015). The decision was appealed and this time the court did find 17 of the works to be transformative, the rest were remanded back to the earlier court for another hearing. Before this could take place though, Cariou and Prince settled out of court (Azran, 2014). The case showed that fair use exemptions had a high degree of latitude. Prince was able to legally appropriate the works without even giving Cariou credit for taking the original photos. His victory was not without cost though. Because Prince had no overt agenda with his art, the court ruled that a work could be transformative despite the artist’s intention (Werbin &Wessel, 2014). Now an artwork in the US must appear transformative to the average observer, whatever the artist’s original intention (Enriquez, 2013).

Cariou v Prince is a telling test case as much of the cultural sharing that occurs online mirrors the behaviours of an appropriation artist. The fact that the case went to trial allows the examination of the key arguments from both sides; often a cease and desist letter is enough to cow any potential infringement, whatever it’s legitimacy. The outcome of Cariou v Prince might have wide cultural effects such as the ability to sample in hiphop music or to create a video ‘mashup’ (Azran, 2014). Should Australia adopt the same system that resulted in Prince’s fair use defence? If Cariou v Prince were to have occurred under fair dealing in Australia, Prince’s art would probably not have fallen within any of the categories required. The closest category in Australia would be satire and it would not qualify as satire as it does not reference the original works. Cariou v Prince illustrates that fair use’s flexibility can also lead to legal quagmires where neither side will know the outcome before testing it in court. Fair dealing on the other hand provides a clear set of measures that can save parties from costly litigation. Herman (2015) notes that the pendulum may have swung too far away from the rights of the artist. Fair dealing requires sufficient acknowledgement between original and secondary works while fair use evidently does not (Herman, 2015). Suzor and Hunter (2015) urge us to look at the bigger picture, the implications for society as a whole; the value of the creative industries is not in the selling of discs and downloads but creative services. The ability to communicate cultural meaning is being choked by misplaced conception of value. It is impossible to know whether Cariou lost money due to Princes activity or, if anything, the added publicity might have helped him commercially. Perhaps Walter Benjamin (2008) was correct when he multiplied a text’s value by the number of times it has been reproduced, the inverse of the current thinking.

This essay has examined the fair dealing framework that Australia currently uses to allow copyright exceptions as well as the fair use model it is considering adopting in the context of the United States. The current fair dealing regime uses predefined categories into which works must fall to receive statutory protection. This does result in a lack of flexibility for legitimate uses of material that might not fit into those categories. The ALRC report (2013), ‘Copyright and the Digital Economy’, recommended that Australia adopt ‘fair use’ as means of adding more flexibility to the copyright regime. Fair use is currently in practice in the United States and so the system can be examined pre-adoption. Cariou v Prince is a copyright suit that occurred in the US that could shed a great deal of light on how the fair use and fair dealing systems differ. Richard Prince’s appropriation work mirrors much of the same work processes of cultural content that is created and shared online. His successful use of Cariou’s photographs is indicative of the kinds of content that might legally be created online now in the US. Some worry now that there might be too much scope to use copyrighted works. Cariou and Prince’s lengthy trial also illustrates the ambiguity in the fair use system. Outcomes are not as predictable pre-trial as fair dealing with it’s category system. Many instances of a modern, digital form of cultural sharing are not protected under the fair dealing copyright scheme. Australians who reproduce content to communicate are therefore breaking the law despite the seeming normality of their actions. Australian legislators must be careful, but not hesitant, to maintain the copyright balance as the means by which Australians communicate changes rapidly in the coming years.